This is hilarious

In her incredible book, What Really Happened in Wuhan, Sharri Markson documents how Proximal Origins was used by scientists — who we now know included Andersen and others — to lobby U.S. intelligence agencies that the idea of a research-related incident was a conspiracy theory, and thus should not be further considered.

A State Department official told Markson:

“Little did we know that prominent Lancet and Nature [Medicine, i.e. Proximal Origins] authors had made the rounds in the IC [intelligence community] to get them on board and to stifle any dissent.”

This raises the very real possibility that when we hear that some U.S. intelligence agencies have assessed COVID-19 to have a natural origin, they are simply parroting what they have been told by who they believe to be the experts — that is, the authors of Proximal Origins. From these agencies, we may not be hearing any intelligence at all, but rather, echoes of the Proximal Origins narrative.

So the Scientists are the tail wagging the dog. It cant be imagined that the Military Health Pharma Intelligence Fusion Complex, using the funding leverage of its front man (HHS/Fauci) put the scientists up to the fraud

These guys are patsies. Let me know when they question guys like Ralph Baric , Michael Callahan, Peter Daszak, Vincent Munster, Matt Pottinger, Robert Malone, Donald Trump then maybe this moves beyond being the Limited Hangout it is. Not that I am accusing them of any wrongdoing but I believe they may have information that will lead to those who did the crime

Also, when is the investigation of the COVID Mitigation Measures and Vaccine Trial Fraud that killed almost 2 million Americans going to begin?

The testimony of Andersen and Garry has gathered a lot of attentions. The transcripts are like 200 pages long for both so I doubt many have waded through all of it.

You can find the links here

https://oversight.house.gov/release/wenstrup-releases-alarming-new-report-on-proximal-origin-authors-nih-suppression-of-the-covid-19-lab-leak-hypothesis/

[Note: This post is too long for some email servers.]

One thing in common with both, which were spaced almost a month apart, is both sides (majority and minority) attempted to determine the feasibility of engineering the virus in addition to how accidental release might be possible. Keep in mind also that Andersen met up with Garry just a few days before his testimony at the annual Creid Network Conference, so might have had a heads up.

For more on CREID you can read here

Fauci’s Self Replicating Funding Machine-CREID

Its important to know that neither Garry nor Andersen worked on Coronaviruses before COVID. They both do work on other emerging viruses with Pandemic Potential (Eg Ebola, Lassa) and like Daszak and Baric are-part of the Fauci CREID network which was formally announced in 2020 during the Trump Administration with $85 million in grants to hand out , including to Daszak who was at the time having his other WIV linked grant rescinded

As Andersen mentioned in his testimony, his CREID grant that was approved in 2020 was actually submitted in 2019. Garry , who is also a CREID grant recipient mentioned in his testimony that work frequently begins before you submit a grant application so you can show the feasibility of the study with preliminary results. He also mentioned that failure to obtain a government funded grant is not the end of the project as money from private foundations is available.

So keep that in mind as you consider the proposed DEFUSE project , which was rejected by DARPA , as Daszak also receives foundation money, including from Jeremy Farrar’s Welcome Trust

Anyways, as both Gary and Andersen answered these questions on the engineering of a bioweapon they both parroted similar points. There was no known (published or uploaded) backbone and the FCS/RBD aspects were considered suboptimal by predictive models so they would not be chosen by a scientist trying to create lethal bioweapon. Case closed.

What they fail to consider is if you were working on a synthetic bioweapon to unleash in the world you would not use a known backbone. And while most private scientists will want to publish the sequence of a new virus as soon as possible, those who fund the development on a bioweapon project are not going to be so foolish, not if they plan to use that virus as a weapon and face potential criminal prosecution.

Second big miss is you would not necessarily want to release a bioweapon that could kill yourself, and the goal of the bioweapon may not necessarily be to kill everyone.

Consider Barics 2006 paper

Will synthetic or recombinant bioweapons be developed for BW use? If the main purpose is to kill and inspire fear in human populations, natural source pathogens likely provide a more reliable source of starting material......

If notoriety, fear and directing foreign government policies are principle objectives, then the release and subsequent discovery of a synthetically derived virus bioweapon garner tremendous media coverage, inspire fear and terrorize human populations and direct severe pressure on government officials to respond in predicted ways.

https://www.jcvi.org/sites/default/files/assets/projects/synthetic-genomics-options-for-governance/Baric-Synthetic-Viral-Genomics.pdf

COVID was likely a bioweapon used in an act of Terrorism. It did not need to be especially dangerous, they had other ways to manufacture deaths (protocols, lockdowns, vaccine deaths) and terrorize the population (MSM, social media), so using suboptimal FCS/RBD may have been by design. Whether the virus turned out more lethal than expected is anyones guess

It bears repeating, if you are going to create a synthetic biological weapon and use it to conduct an act of Terrorism, and you want to get away with the crime and avoid a long vacation at GITMO or being hung, you will design the weapon so it appears suboptimal, illogical so that it may appear natural, plus you would not want to make it so lethal as to kill yourself and loved ones

Listen here to Ralph Baric talking about

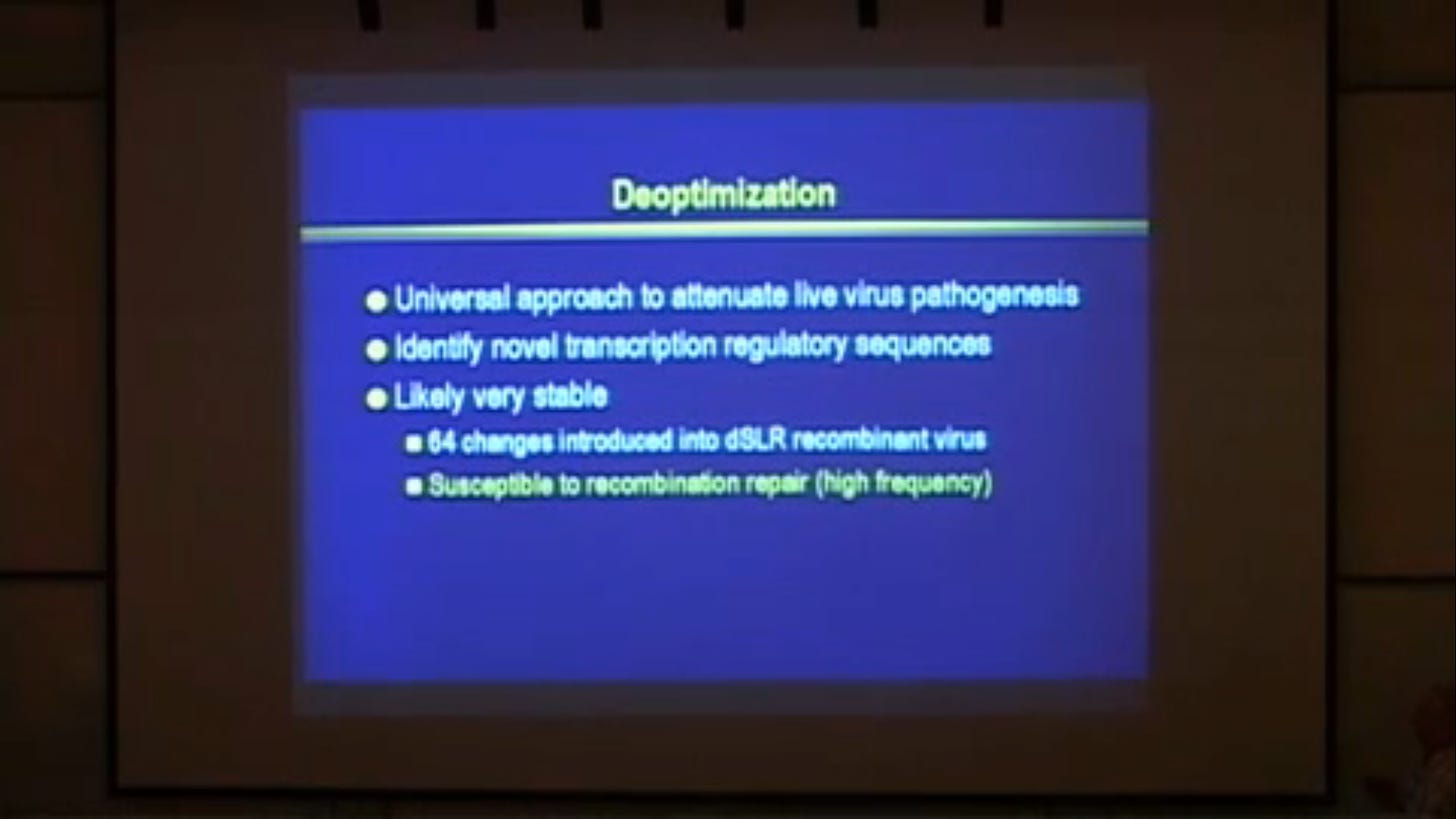

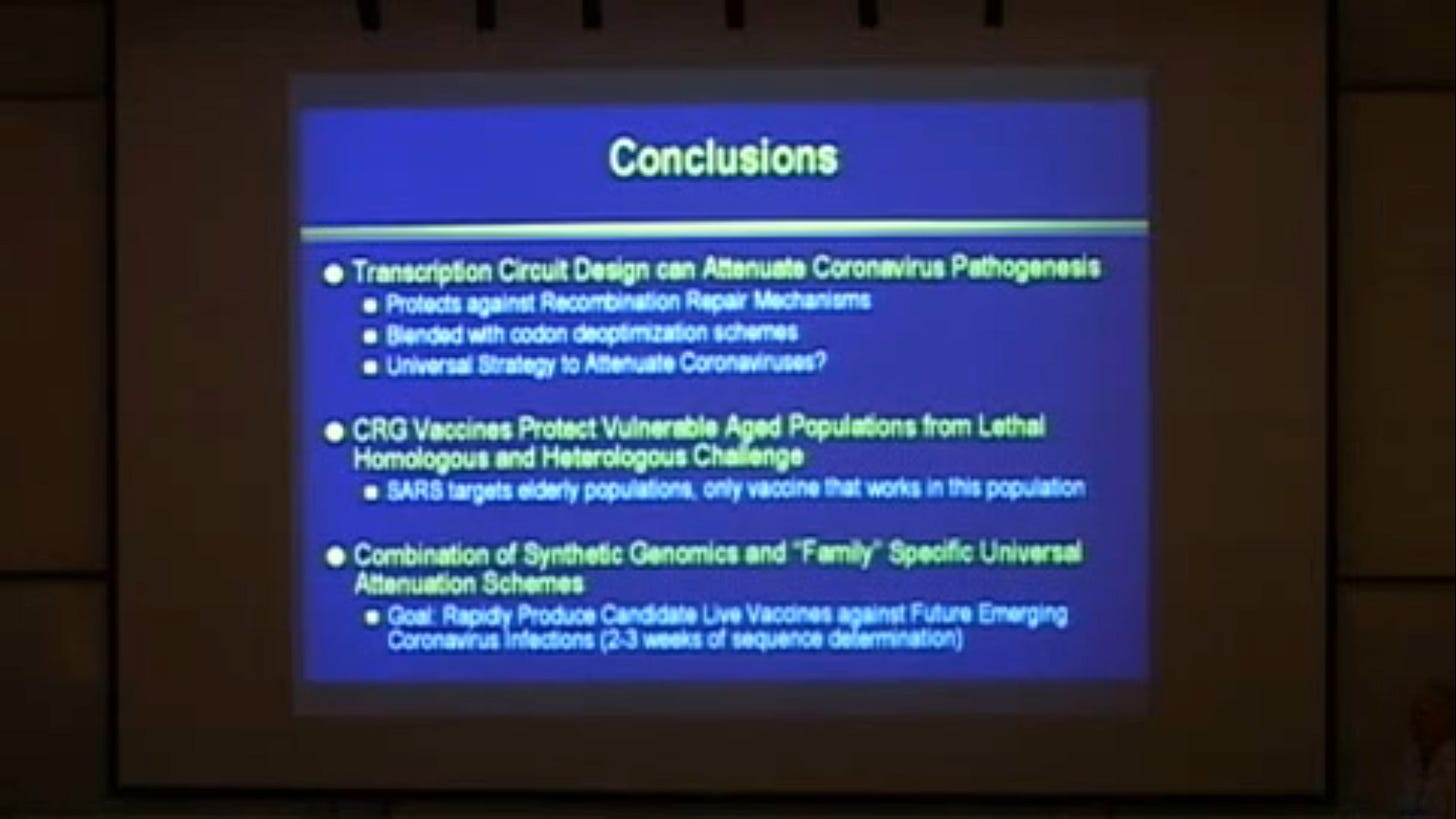

Deoptimization-Transcription Circuit Design

—

Sorry for the blurry screen shots but this was 14 years ago when video quality was not great.

Baric was talking here about engineering SARS to become less pathogenic and to find ways to stabilize it so it would not revert to virulence which is possible via recombination. This is important for the purpose of developing a Live Attenuated Virus Vaccine

Furthermore, since biological weapon research is illegal, it is frequently masked as biodefense research, hence the use of HHS and Fauci to attach legitimacy to the research. With any weapon related technology, research that leads to knowledge on how to create new or improved weapons systems is frequently not published and is classified, sometimes for decades. So to say such and such is not possible based on publicly know tools and techniques is naive. Not all of this technology is in the public domain.

Whoever funds the research gets to decide if the results are published, and much of this research is funded by the fusion of Military-Intelligence-HHS agencies that has taken place since 9/11

So moving on, they needed to create a novel synthetic virus with a unique genetic signature for which they could develop PCR tests to track cases and deaths which they would then use to terrorize the population and get them to take the vaccines and monoclonal antibodies and expensive antiviral drugs they would develop. Mission Accomplished.

They also needed to make a virus that would not mutate itself out of existence too quickly, like SARS. Baric published a paper in 2018 on doing exactly that. His ostensible purpose was to create a stable Live Attenuated Virus Vaccine, perhaps related to the DEFUSE project goal of creating a self spreading vaccine for Bats

You can read more about that here

Was Sars-Cov-2 a Self-Spreading Vaccine?

A transmissible live virus is by definition is a natural self spreading vaccine. After we get infected we are immune although for certain respiratory infections the immunity is short lasting and it mostly helps only to prevent serious disease when reinfected. So even with natural immunity its not that great with respiratory viruses, which explains why we have never developed a great vaccine for respiratory diseases. They have developed some good vaccines for systemic infections that might be transmitted by a respiratory virus , but where the vaccine immunity provided is against a disease process that takes place outside the mucosa, like measles and polio, and not necessarily at stopping the virus in its tracks at the mucosa.

So anyways, as you read the transcripts they repeatedly mention that some of the tools and techniques used to manipulate coronaviruses were not used in any of WIV’s published works.

This is where having a guy like Ralph Baric testify would be so interesting. If there is anyone who could engineer a Pandemic Coronavirus , it is this guy. He is literally the Father of Coronavirus Science. He was studying there effect in the heart in the 80’s and is an expert in reverse genetics, humanized mice and manipulating viruses in a way to hide such manipulations with his no see’um technique.

He also signed a Material Transfer Agreement with Moderna relating to coronavirus vaccine development and was involved in work with Remdesivir. He was offering toilet paper at $10/roll in March 2020 on TWiV having had the foresight to stockpile a case (maybe more?)

Yes indeed, Ralph has been as well hidden and hard to get as his humanized mice with human lungs and humanized immune system.

In Andersens testimony he explained that Baric was excluded from the call on origins because “Ralph had very close associations and collaborations with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, for example. So if this did, in fact, originate from a lab, then, of course, he would not be a person to have on a call like this”

This is absolute nonsense. There is nobody else more important to have on such a call. If there is anything Ralph does not know about coronaviruses, it is not known by anyone

As I mentioned earlier, Ralph, Daszak, Garry, Fauci, Andersen were all part of the CREID network which informally was operating before its formal approval/announcement after the pandemic began. Indeed, no doubt WIV was considered part of this network until they were excluded due to political reasons after the pandemic began.

Ralph was likely not on the call because he was being protected. His fingerprints are all over the crime scene. Garry and Andersen are just as conflicted, because they are all tied together via the CREID NETWORK , which funds all of their GOF research. They were the designated patsies.

If Lab Origins were implicated early on, the CREID network would have been disbanded, they would have missed out of millions of research dollars that inevitably lead to valuable patents and other financial opportunities, not to mention all funding for GOF would have been suspended for years. Sometimes it pays to be a patsy.

Proximal Origins was clearly a Conspiracy to Cover Up a Crime, or at least an Accident, that may result in another crime or accident , sooner or later. But let me suggest it was perhaps more than that.

First you need to put yourself in the mind of the real Criminals, the “Higher Ups”. Not the Scientists who are mostly just greedy useful idiots turning tricks for their Pimps in exchange for grants and patents.

You are executing the Greatest Crime in History that will kill millions by arranging the creation of a fairly benign but novel synthetic virus ,which is pretty dangerous to elderly people who don’t get proper treatment. You can make sure they don’t get the proper treatment and then get them to take deadly vaccines. But the virus is the key for this.

Those participants on the Left saw the benefits of a Pandemic in reducing population for their Net Zero Carbon Agenda. Those on the Right who participated saw the benefits of reduced Social Security, Pension and Medicare Payments in coming years. Both sides saw the business opportunities

As a participant in the Crime you want to make sure you are not a suspect and don’t get investigated. You have planned this for years. You know the virus must not look engineered, so you do some suboptimal and illogical manipulations , release it near a wet market that is near Chinas BSL 4 lab, thus setting 2 narratives, natural origin or accidental lab release by WIV in China. I say accidental is because nobody would imagine China would release it in their own back yard (simple people are unable to appreciate what true evil can do).

You time it around the Wuhan Military Games, perhaps to set up a narrative that the games facilitated the global spread, or perhaps to set up your partners (China) narrative for their domestic population that the US released it during the Wuhan Military Games

I wont try to explain who or how the virus was deployed. Use your imagination cause we will never know. Maybe Ralph sent them a virus for DEFUSE and they assumed it was just a benign virus , and did not take adequate protection. Who knows?

But in any event China played its role in the crime at the start.

People “dropping dead” on the streets of Wuhan

The Guardian officially launched the pandemic with their article, “A man lies dead in the street: the image that captures the Wuhan coronavirus crisis.”

Héctor Retamal based in Shanghai and employed by Agence France-Presse (AFP) somehow got to Wuhan, took several pictures, and they were distributed worldwide by Getty Images.

At the time, this photograph seemed like a major scoop that would be embarrassing to the Chinese government. Dead guy in the streets. The “emergency staff in protective suits” look startled implying that the photographer should not be seeing this!

But let’s think about this for a moment. In China, a photographer for a foreign news agency would have a government minder assigned by the Chinese Communist Party to watch his every move. In order for Mr. Retamal to take this photograph, the government minder would have needed to allow him to be there in the first place, and that permission would have come from on high.

Even once Mr. Retamal took the picture he would have needed the ability to get it out of the country — yet his government minder did not confiscate the camera nor prevent him from accessing the internet — which reinforces the point that the Chinese government wanted this photo to get out. The question is why?

Furthermore, everything about the image is contrived. People did not just die in the streets from Covid. The body was too neat — he just fell flat on his back in a perfectly comfortable resting position with no limbs akimbo? Presumably his head would have hit the pavement, why was there no blood? Since the government allowed the photo, then these workers probably were not surprised, rather one might surmise that they turned and posed for the camera in order to create the maximum effect.

This then became a style of reporting — hapless Chinese workers in hazmat suits and people dying in the streets of Wuhan. The Daily Mail provides a particularly egregious video montage of these images, Footage emerges of men and women ‘unable to stand in Chinese city at the centre of the coronavirus outbreak.’

Swiss Policy Research conducted an analysis of the Wuhan Covid photos and videos and concluded that many were either staged or had nothing to do with Covid (in fact they were “drunk people, homeless people, road accidents, unspecified medical emergencies, and even training exercises”). So why were they released and marketed to the public as Covid-related images?

In retrospect, it now appears that we were being presented with the opening scenes from the movie Contagion transposed from the movie theater to the newspapers. Contagion, more than any other movie, trained us to expect this to happen and now sure enough, it was happening!

The deadly virus in the fictional films starts in Asia, spreads via well-intentioned international travel, and next thing you know, people are dropping dead. Contagion even featured an Asian wet market as being at the epicenter of the epidemic.

Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist at Columbia University who was a consultant on the film Contagion, was part of the team that covered up the lab origins of SARS-CoV-2 at the behest of Tony Fauci during the early days of the pandemic — while the Guardian was running the photograph I showed above.

[According to Ian Lipkins testimony to the House Select Committee

https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2023.04.06-Lipkin-Transcript.pdf

in April he worked with the CIA and had went to China in January 2020 to offer his help, one wonders if he helped China rehearse their script and brought a few copies of Contagion with him. He was quite proud of his role in making that movie it seems]

So moving on, you are satisfied that you have a pretty good cover most people will accept, either natural origin or accidental Wuhan lab release. But you also know there are many crumbs leading to UNC-Baric, Fauci, DARPA, RML, Moderna , etc so any real investigation might be dangerous. Fortunately you have support from both parties to cover it up, much like they did with the JFK HIT and 9/11

You know that once the Natural Origin argument fell apart, things could get dicey. Maybe they had an agreement with China that they would produce a fake intermediate host and China double crossed them, perhaps to retaliate for Trumps trade war. Who knows.

They could also anticipate that once an investigation into Wuhan Lab Release was started they had to discourage anyone from feeling the need to look beyond Wuhan by preparing the seed they will plant at the right time.

So they set up a committee of Captured Scientists, taking care to keep Ralph Baric well hidden, have them send a bunch of emails and slack messages discussing only the possibility of the virus being engineered by Wuhan and then accidentally released while preparing a Paper that leads one to conclude it was Natural Origin, and at the right time release this information and put up a couple of Limited Hangout Investigations taking great care to keep Ralph Baric well hidden.

Andersen

“I think the main thing still in my mind is that the lab escape version of this is so friggin' likely to have happened because they were already doing this type of work and the molecular data is fully consistent with that scenario.”

What more is needed to convince the herd that it was a Wuhan Lab Release? By showing evidence that key scientists and Fauci were conspiring to cover up Wuhan Lab Release, so clearly it was Wuhan Lab Release!. Case solved! A few patsies get thrown under the bus and the real Criminals Walk away with their bag of loot and prepare the next heist.

Too far out? Think about it

Moving on, Jeremy Farrar who allegedly organized this paper also funded fellow Brit Peter Daszaks research via Wellcome Trust, so he was just as conflicted as Ralph Baric. Clearly Fauci was leading this from a distance as his fingerprints are all over the crime scene as well, not to mention his real bosses who shall not be named.

What other evidence might there be that this was a deliberate release of an engineered virus. There is clearly means and motive. A lot of folks made a lot of money on this caper. But thats not enough. There were signs this was an organized operation as I tried to convey in the below post

I wont rehash it all but we can start with Fauci predicting an outbreak during Trumps term in January 2017. Gates setting up CEPI in 2017, the NSC under Josh Bolton drafting a Pandemic Plan in 2018 that was adopted for COVID in March 2020. A series of exercises/simulations (2017-2019) from SPARS to Clade X to Crimson Contagion to Event 201. Moving the Pandemic Stockpile to BARDA from CDC in October 2019. Unlike CDC , BARDA is exempt from FOIA requests.

Then there was Gates big investment in BioNTech in September 2019, and Trumps EO making development of a Universal Influenza Vaccine a National Security Priority, the removal of the last CDC epidemiologist from Beijing in the summer of 2019, and Modernas MTA with Baric in December 2019.

And of course then we have the White House Council of Economic Advisers preparing a cost estimate for a Pandemic (came out at &400 billion to $4 trillion, actual cost $5 trillion, not bad) at the same time the Repo Mkt Crisis hit and Larry Finks Black Rocks “Going Direct” plan was first implemented . This would be expanded in March 2020 when he was given $400 billion of the Feds Money to invest in companies going along with the Operation.

Then there was the curious matter of CIA-DARPA man Michael Callahan being in Wuhan in December 2019/January 2020, and Matt Pottinger who was an Old China hand and retired Military Intelligence Officer who was Trumps assistant NSA adviser pushing Chinas lockdowns and masks, and NSC doing the same with their adopted Pandemic protocol in March 2020, and the White House Classifying all discussions of COVID from January before the US had 1 COVID DEATH.

Beyond that the entire developed world acting in an extraordinarily coordinated fashion in dumping the WHO pre-COVID Pandemic protocol and pretty much doing the opposite , while all acting in a coordinated fashion to block the use of repurposed drugs and skip essential safety tests for cell/gene therapy vaccines. Pretty much every country adopting in Lock Step what we now (some of us much earlier) know was wrong.

And we can look back and see how combatting misinformation was a theme in all of the Pandemic Exercises during a time various organizations (eg Truth Initiative, Newsguard) and new agencies (CISA -2018, GEC-2017) were being created in the building of the Censorship Industrial Complex. They all played a huge role in censoring information on COVID

Ok, lets get on with Andersen’s and Garry’s testimony. Before I do , I extracted some bits from the link below which summarizes some key points

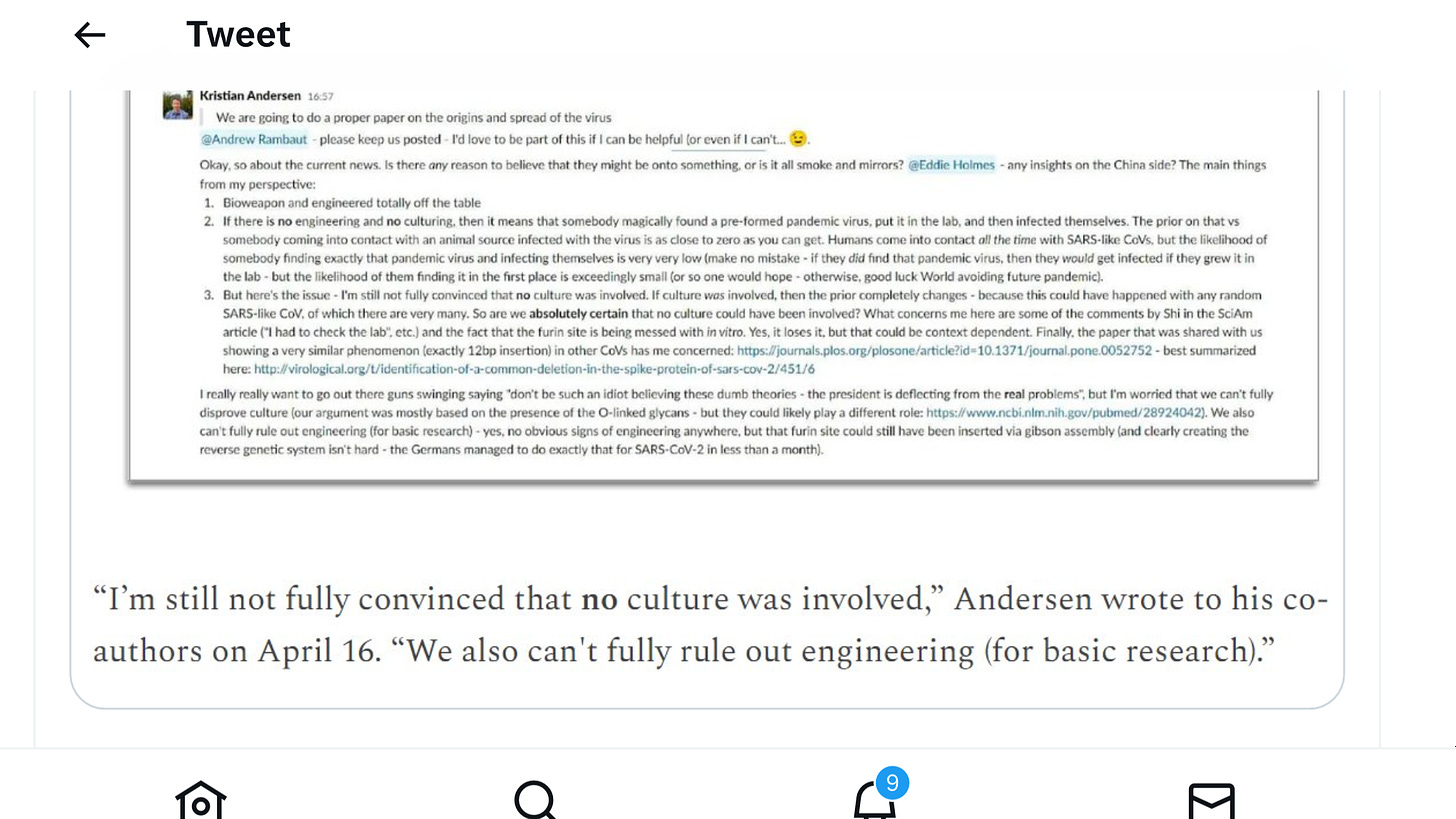

Andersen still suspected that a lab leak was possible in mid-April, a month after Nature Medicine officially published “Proximal Origin,” and two months after the authors published a preprint.

But, Andersen told Congress, after he and his co-authors had carefully considered the evidence, they concluded that “culturing” in different cells or animal species in a lab, which can make a virus more infectious and well-adapted for humans and other animal species, had not occurred, and that the virus had spilled over from wildlife to humans.

“By the time we published our final version of Proximal Origin,” Andersen explained in his written testimony, “I no longer believed that a ‘culturing’ scenario was plausible.”

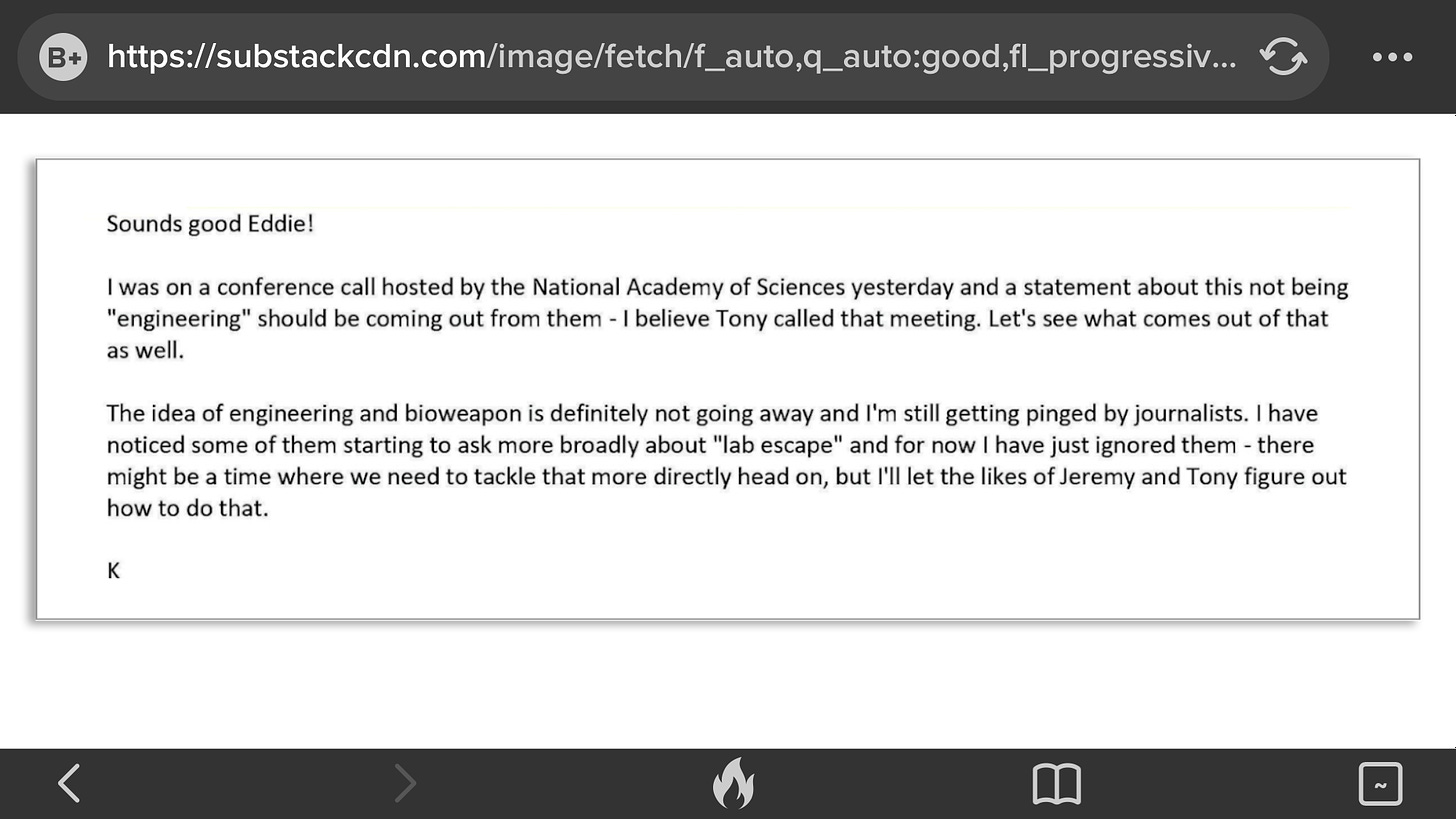

On February 3, Andersen attended a meeting arranged by Fauci at the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), the august science advisory organization created by Congress in 1863 to be scrupulously independent and above politics.

The Academy meeting on February 3 occurred directly before Andersen, and others changed their tune for plainly non-scientific and apparently political reasons. Other attendees at the February 3 meeting included Collins and representatives from the FBI and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI).

One of the new messages shows that Andersen was anxious about his association with the Academy. “One main problem I have too,” he wrote on February 19, is that my name is on e.g., the NASEM letter and other 'official' things looking at this - so I need to be able to deflect potential future enquiries that could directly involve/name me.”

“I mean,” said Andersen to the House Subcommittee, “it was clear that the White House Office of Science Technology Policy at that February 3rd conference call, Dr. Fauci, in my initial email to me, talked about contacting the intelligence community both here and in the United Kingdom. So that's what my assumption is, that when we're talking the higher-ups here, the White House was aware of this.”

While we still don’t know if those referred to as “on high” or “higher ups” are Fauci, Collins, Farrar, the White House, or the intelligence agencies, it’s clear that the authors were not operating independently.

Below I have extracted some of what I felt interesting in Garry and Andersons testimony (links above). Some of it is redundant. You can read on or exit. I wont hv much commentary.

Andersen

https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2023.06.16-Andersen-Transcript.pdf

And then the other major grant we have is what's called a Euro 1. It's also a Center grant under the NIH, which is called WARN-ID, or the West African Research Network for Infectious Diseases. It's under the CREID portfolio, the CREID centers at the NIH, focused on understanding emerging infectious diseases.

And this is a joint grant with what's called a contact PI, my colleague Bob Garry is what's called an MPI, a multiple PI, and then my former adviser, Pardis Sabeti at the Broad Institute, is also a PI on that grant.

And then we have four African partners on that grant. And, in fact, all the research is focused in Africa, from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and Senegal.

And this is a grant that was awarded in 2020, written just before the pandemic in June of 2019, I believe reviewed in 2019, and, of course, was initially focused on just emerging infectious diseases, RNA viruses specifically.

[CREID WAS not formally announced until after the Pandemic, so interesting they were awarding grants before they existed]

Of course, the pandemic happened following the award of that grant, so much of that research has been focused on COVID-19, but also on malaria and many other infectious diseases.

But I have not had any direct contact with David. I don't know David (morens). I just met him 3 days ago, 2 days ago when I was at the CREID -- annual CREID meeting at the NIH, was the first time I actually met David in person.

—————————————————————

A This is not specific to China. We can look at our own response to SARS 2. Did we cover that up? To an extent, because we weren't really testing for it. I have seen the same sort of practices early. It's important that we understand early during an outbreak. We don't yet know it's going to be a pandemic. It's, generally speaking, chaos on the ground.

I've seen this personally. I was in West Africa during the Ebola outbreak, for example, just as that was emerging, during; after too. And it was the same sort of things where, I think, what will later be seen as obfuscation is common practice. And there's a few reasons why, which is that maybe it'll just go away. I mean, China closed down the Huanan Seafood Market.

———————————————————

A…..when I realize it's Jeremy Farrar, because, again, I didn't know that based on the conversation with Eddie. We talk about my concerns and talk about, like, look, we need to get a group together to discuss these concerns that I have, and we need to select people that are unconflicted. So we did.Ralph Baric, for example, is a name that came up. We all know Ralph. Ralph is a very important coronavirus biologist. But we also knew that Ralph had very close

associations and collaborations with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, for example. So if this did, in fact, originate from a lab, then, of course, he would not be a person to have on a call like this.

[Not inviting Ralph Baric is just Insane]

Peter Daszak is another person that, of course, came up for the same reasons, because they had been co-publishing.

Jeremy gets all of this set up.

[LOL, Jeremy at Wellcome Trust is one of Daszaks funders]

He, I'm sure, has been in touch with Tony Fauci at the time, reaches out to Dr. Fauci, asks him to call me.

I have a quick phone call with Dr. Fauci. I sort of relay what I have found and what the early views of this is, round receptor-binding domain, the furin cleavage site, a few other features.

And he, Dr. Fauci, specifically mentions the furin cleavage site in his email to me following that telephone call, but he also makes it clear that he will contact the intelligence community and sort of run it up the chain in the United States Government.

[Of course, Fauci has to report to his handlers]

I don't know the result and outcomes of any of those other than the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy did establish a meeting on February 3rd to look into this as well.

But following that call, essentially what I recall Dr. Fauci saying is to the effect 1 of -- and I'm paraphrasing him here -- but basically saying that, look, if you think this came from a lab, then you should really consider writing a paper on it so it can be peer

reviewed and judged by the community

And that's the purpose of the conference call, which, again, is completely organized by Jeremy. Jeremy runs the call. I honestly don't remember Drs. Fauci or Collins even chiming in on the call itself. I'm sure they probably had questions. But this is not their area of expertise and they were just there to hear the scientists discuss what I had brought up. And the discussion is primarily between myself and Andy Rambaut, Eddie Holmes, Christian Drosten, Ron Fouchier, and Marion Koopsman. Those are the main factors I remember here.

[Why is a British National, The UK’s equivalent to Bill Gates calling the shots here. As mentioned, Jeremy Farrar’s Welcome Trust also funds fellow Brit Daszaks Eco Health Alliance]

————————————————————

We discussed what we found to be unusual in the viral genome, including the receptor binding domain, the furin cleavage site, the damage, one site which is a restriction site, and also just outlining some of the research that have been ongoing at the Wuhan Institute of Virology

Q Regarding the Wuhan Institute of Virology, what did you present?

A Just in broad terms, the fact that they were culturing viruses from bats, or attempting to culture viruses from bats, isolate viruses from bat samples, which is not easy, in BSL-2; and, also, some of their chimeric work using WIV-1, for example, which is a common backbone that they are using; as well as just the general strategies around creating chimeric viruses, much of which I believe was done in BSL-2 and, as I mentioned, animal work in BSL-3.

[No mention of this being inadequate?]

Q Do you do any chimeric work in your lab?

A We don't do chimeric work, but we have done -- I've done so in the past, as part of my Ph.D. We have done work on Zika virus, for example, where we have introduced naturally occurring mutations into what's called clones of the virus and then cultured those. That's completed work, but that's what we have done in the past.

Q Does chimeric work come with more risks than just culturing?

A Chimeric work requires culturing.

Q Okay.

A Chimeric work is -- you know, "risk" is a nebulous term, but in chimeric work you can work with high amounts of the virus, versus when you culture or attempt to -- I'm saying "culture." Really, what I should say is "attempt to isolate" a virus.

So, for example, if you have a bat sample from which you have sequenced the viral genome -- so you know that this virus was in that sample. You don't know whether the virus is active, whether it can actually be cultured, right? But you know that at least there's some evidence to suggest that that virus is in that sample.

And what you then try to do is, you take that very sample and you put it on top of cells, typically Vero cells, and then you attempt to isolate the virus -- so, basically, getting the virus from that sample to actively replicate in the cell culture itself such that you can isolate the virus.

Q -- Dr. Fauci sends an email back, where he kind of outlines that you both talked about your concerns that you've discussed here today and that, if they are validated, he would have to talk to the FBI and Jeremy Farrar would have to talk to MI5.

Did that surprise you?

A No, it did not surprise me because, in fact, I was -- when I initially was concerned with, you know, the early findings that I had, I was, myself, considering, what do I need to do here? Right? If I believe this could've come from the lab, who am I supposed to contact?

And I thought about -- I have some brochures and pamphlets from, like, the FBI, I believe. So I was like, am I supposed to call the FBI? Am I supposed to call the CIA? What am I even supposed to do here?

All of that sort of -- I didn't go through with any of that because then, ultimately, Jeremy Farrar -- I talked to Eddie, right? And Jeremy Farrar then set up the conference call, and then it was sort of moving from that direction.

But none of this surprises me, no. Whether he did it, of course I don't know. But, as I've previously mentioned, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy set up a conference call on February 3 --

Q Uh-huh.

A -- where I raised many of the same concerns that I had, although the idea of engineering at that stage was largely -- I had largely dismissed that at that point.

[ 2 days later you had already dismissed it? Or more likely you were told to dismiss it]

Q On 797, in the middle there, you state, "The unusual features of the virus make up

So I won't ask you if you remember the email because -- I do, yes.

Yep. It's a very small part of the genome, so one has to look really closely at all the sequences to see that some of the features potentially look engineered."

Which features, at that time, were you talking about?

A Yeah, I'm talking about, like, the furin cleavage site, the receptor binding domain, and a few things associated with that, the BamH1 restriction site that I mentioned, as well as some features associated with that -- basically, what I then end up presenting the next day at that conference call.

A For the record, let me just read out the full paragraph, if that's okay?

Q Yeah.

A "We have a good team lined up to look very critically at this, so we should

know much more at the end of the weekend. I should mention that after discussions earlier today, Eddie, Bob, Mike, and myself all find the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory. But we have to look at this much more closely, and there are still further analyses to be done, so those opinions could still change."

A- let's just talk about the receptor binding domain and the furin cleavage site.

This particular receptor binding domain, at the time, we had not seen a version of that. But early analyses on that, our own as well as those of Ralph Baric and others,

suggested that it was a good binder to human ACE-2, as well as multiple other species, but definitely human ACE-2.

This is part of the virus, right, the contacts, that ACE-2 receptor on the human cells. And

6 the contact residues specifically were different in SARS 2 than they were, for example, SARS 1, yet they appeared to be a good binder.

So I was perplexed by that. We had not seen that site before. Of course, the

furin cleavage site itself, which we had not seen in sarbecoviruses before.

But it's important, again, to understand that that's the extent of the early

considerations, because, of course, furin cleavage sites are broadly, you know, seen in

coronaviruses, including many betacoronaviruses, which I didn't know at the time.

But that's basically my comments. And when I'm saying the genome is

inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory, it's a bit of a fancy way of basically saying, like, look, guys, I think this could be engineered.

—————————————————————-

Q To the best of your recollection, did you discuss the subsequent papers to "Proximal Origin" that you had been working on with Dr. Fauci?

A No. I mean, I submitted them to -- because we are funded by the NIH, so when we have preprints and papers going out, we submit them to our program officers. And I believe our program officers had discussed the preprints and papers with Dr. Fauci.

—————————————————————

Q So, in -- I'll use the draft -- the line right before which you said: "The initial views of the experts is that the available genomic data are consistent with natural evolution."

A Yeah.

Q So that would be consistent with, you've had conversations between February 1st and February 4th where you changed your mind?

A Yes, the idea that what I had observed early on was inconsistent with the expectations from evolutionary theory was put in the ground by then, because, in fact, it wasn't.

There were several things about the furin cleavage site I had realized. For example, initially, I thought it was pretty much a perfect furin cleavage site. It's not.

It's actually a pretty bad one. So I realized it was out of frame, for example, which an

engineer would basically never do.

[ An engineer creating a bioweapon not wanting anyone to think it was engineered might do so]

So, yes, my opinion on, like, being inconsistent with evolutionary theory had been

put in the ground. And the engineering aspect of that too, I basically said, okay, that

doesn't make sense. But, of course, there is the version of the lab leak which has to do with a cultured virus, which I was definitely still considering and probably at the time found the most likely explanation.

Q But it seems as if there are two main arguments in that regard, the first being, okay, the virus's receptor binding domain mutations at the key amino acid residue sites would have been predicted by a computational model to be suboptimal in their binding affinity.

A Right.

Q Okay.

And then, secondly, SARS-CoV-2 does not reflect the use of a known viral backbone, which one would expect to be the case.

A Specifically, it's a short paper that we were asked to shorten further. But I think what's important, too, here is that you look at that furin cleavage site, for example

But, yeah, those are some of the main arguments, that if you just look at the

architecture of the virus itself -- the furin cleavage site, receptor binding domain, all these things -- it's that, is this one of that example, where it's just messy enough but it just works well enough, that really points to nature? That's what evolution does all the time, right? It never makes perfect, but it's these weird solutions that just work well enough.

And, of course, what we have since seen is huge evolution of the virus itself, right? So, clearly, it wasn't well-adapted to the human population, right, once it got a chance to take off.

[ sure, going from lab culture /humanized lab animals to infecting billions of humans wearing masks , social distancing and taking HCQ/IVM , increasing natural immunity and then vaccines results in evolutionary adaption]

Q So, to just drill down for a second on the receptor binding domain and the predicted binding affinity of those mutations --

A Yeah.

Q -- to test if I understand it correctly, the idea is, if somebody were to design a virus from scratch --

A Yep.

Q -- they would never have rationally chosen this particular design --

A Right.

Q -- because they would have consulted the models, which would have told

them this was not an optimal binding.

A Yeah. We knew, based on, you know, much of the great research that

Dr. Baric did with SARS-1 is that based on that were predictions of here's the optimal way in which a sarbecovirus will bind into the human ACE2 receptor. That is described in the literature, right? So, if you were to design a new receptor binding domain, presumably you would choose that, right? That would be the logical way to do it.

[Not if you were a criminal who wanted people to think it had a natural origin]

And SARS-2 doesn't have that at all. It has a completely different solution, right, which we had never seen before. Yet it still appeared to bind well to the human ACE2 receptor -- which we now know, yes, it does bind well to the human ACE2 receptor, but it binds well to a lot of other ACE2 receptors, right, not just human.

[Maybe we should ask Ralph about that]

So, yeah, that's the idea behind, like, if you were to build this from scratch, you would take the solution that you already know works well. Because that's how science is done, molecular biology is being done.

Q Okay. Great.

And so what, if anything, does that argument tell us about the possibility of, for example, chimeric work to test the emergence potential of natural viruses?

A Chimeric work -- I mean, if they took a totally novel virus, created a totally new cloning system, for example, and put in totally new things, of course that would be indistinguishable from a natural emergence, right? The thing is, though, that, again, it's just not how science is being done. I mean, if you look at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, you look at their papers, right, they always did it the same way, right?

That's not to say that you couldn't possibly create a totally novel virus with no scars (ph). Of course you can, right? I mean, but that's pure speculation. If you look at what they've previously done -- which is what I was very focused on in the beginning, because it was just like, I just have to find any piece of this virus or features of this virus that have been used before -- cloning sites, you know, backbones, whatever, right, that they've used previously. Because, again, they're always doing it -- pretty much always doing it the same way, right? If I could just find that, it would nail the lab origin, right? And I just couldn't because it doesn't exist, right? It's just not out there.

[ Meaning the Engineer did a good job hiding his engineering. The Father of No See-Um or whomever may take a bow]

Q So I think that dovetails nicely into that second half of the engineering argument, which is, the virus's backbone is not known, has not been previously described.

A Right.

Q Can you talk a little bit about why you would expect that would be the case if it were a laboratory engineering for purposes of this conversation?

A Yeah. Again, that's because that's how science is being done. If you have stuff that works, you keep using stuff that works.

And the Wuhan Institute of Virology, for example, has been using WIV1 as a backbone, as well as a few other backbones, so WIV1 is sort of a workhorse there that they keep using for different papers to test, you know, receptor binding domains, for example, spike proteins. They subclone it into WIV1. And this is not WIV1, right?

[Maybe Ralph sent them a new Virus or they discovered a new and unpublished backbone]

There are other described systems out there from Ralph Baric and other authors too, and this is not that either.

And that's the expectation based on the published work that you have based on the way in which they do it.

[Bioweapon Engineers are not limited to published work]

But even so, too, is that they use a specific set of restriction enzymes, for example, in most of their work. And, again, this virus does not contain those restriction enzymes, right? So, even if they were to take a backbone that we haven't heard about and haven't seen before, they are not even using the kind of system, BAC cloning system, as they are called, B-A-C cloning systems, as they used previously.

Q And restriction enzymes are a method by which to conduct genetic engineering?

A Yeah, these are basically molecular scissors. So you can precisely cut out genetic material using restriction enzymes. But --

Q Is it correct --

A -- restriction enzymes are not the only way to do this. There are seamless cloning technologies that, for example, Ralph Baric has been pioneering and using a lot.

But, again, that's not -- the vast majority of work that you see at the Wuhan Institute of Virology is not using these types of technologies.

[He just implicated Ralph there but its not like WIV couldn’t have used the same method ]

Q Is there an extent to which the Wuhan Institute of Virology possessed bat virus sequences that, themselves, were not published or known in their entirety by the rest of us?

For example, RaTG13 --

A No, so we did, right? Because they had released fragments of that sequence, right? The famous 4991 sample, which they released in 2016 I think, which,-- was released by Wuhan Institute of Virology in January, I think, of 2021? [2020] Yeah.

And as I've learned recently, the "13" indicates the year in which they [got]the sample.

A No, so we did, right? Because they had released fragments of that sequence, right? The famous 4991 sample, which they released in 2016 I think, which, you know, you could see that that's the most closely related, but it ain't SARS-2. That's the fragment where, you know, initially they just got the fragment and then getting the full genome of the virus, which I believe they probably got most of that in 2018.

Q Uh-huh.

A And, as we know from the work with Eddie Holmes, is that they actually put it on NCBI, right? But it was on their embargo and then they forgot about it, and then it was released together with the other things they had, right?

[Maybe Ralph got that sequence from WIV and inserted the FCS onto the spike and assembled ITVwith another backbone taken perhaps from unpublished bat viruses from Laos which the Navy has been collectible since 2017]

So is it possible that they could've had a novel virus that we don't know about?

Of course it is. We're not dismissing that possibility. We're just saying that the idea that they would do that and that that would then somehow end up in, you know, the next pandemic being associated with wildlife and things like that, in our opinion, given how viral emergence works, it's just not possible.

Q That's a little bit of my question, or it's a version of it.

A Yeah.

Q Is there an extent to which that argument has a human component to it?

A Of course. It's our interpretation, right? It's our interpretation. People

can agree or disagree. And there are certainly a lot of scientists that disagree with our interpretations of the data. That's a question of, how do you interpret the data?

And that's why we publish it in the scientific literature. It's peer-reviewed, which means that the expert that saw this paper -- which, I should say, because you have our earlier versions of the paper where you can see some of the wording, for example, is softer, one reason for that being that, by the time we published that first version, right, I was still thinking that certainly the tissue culture passage was quite plausible, right? -- is that the process of peer review means that you incorporate changes, you shorten it down, you make some of the language punchier because you don't have three sentences to write the same thing, you only have one. You only have so many references you can put in, so you can't reference all the different work that has been ongoing, right -- is that that's just part of peer review, scientific publishing.

And then we put that out there and saying, like, this is what we think. And some of it, we say, like, we feel that the evidence allows us to dismiss this. Others, we say, our opinion is that -- for example, we say that we do not believe that any type of a lab leak is plausible. But we also make it clear that the evidence does not allow us to prove or disprove any of the versions of the lab leak -- of the emergence events that we discuss in here, including the lab leak.

And we still -- to this day, that is still the case, except, though, that the evidence has only gotten stronger for a natural emergence of this, because we didn't have all the data available to us at the time. But additional evidence has only further strengthened the conclusions that were made in this particular paper.

Q So, just chatting about each of those in order, the pangolin receptor binding domain, can you talk just for a moment about what that was and the significance of it?

A Yeah. I think what's -- or, actually, let me talk about the evolution of the

thinking of this, which is why the pangolins are being brought up. Because, initially, when I raised these concerns, remember that I said the main two things I picked up on was the receptor binding domain and the furin cleavage site.

Now, the receptor binding domain, by the time we wrote this, they said, well -- they existed on these pangolin viruses. So, clearly, that's natural, right? But --And just for clarity for all of us, the pangolin receptor binding domain has six-- key amino acid mutations. Yes, which have now also since been identified in bat viruses, right? So, clearly, this is a natural feature.

The reason why we specifically bring up that argument here is that -- initially,

again, I was concerned about engineering, but could, you know, pretty quickly dismiss that version of it. But I thought that, yeah, but, you know, this receptor binding domain, which has found its own way to bind pretty well to human ACE2 receptors, right -- is that, could that have been a result as passage of the virus on, for example, human lung cells, right, or cells expressing human ACE2? And you do a serial passage of that, and that will look like evolution out in the wild too, right? But now it's actually specifically for humans. And that would fit, right?

And I thought, well, this has a new receptor binding domain we have never seen.

These residues are unusual, in the sense that they look to bind well but they clearly are

not what we have predicted, so it's not engineering, right? But it could be this passage

idea.

[ Passaging in humanized mice is part of the engineering]

That argument totally falls apart as soon as you see that pangolin virus, right? Once you see that, actually, that pangolin virus has exactly the same binding residues here, that argument just falls apart.

And it took me a while to, first of all, realize that because realizing the importance

of the pangolin -- really incomplete data, so initially I didn't actually look at it, right?

[Can anyone really trust any papers out of China post Pandemic?]

And it just took a while to go, sort of, like, oh, actually, that doesn't make any sense

because of this receptor binding domain. Right? So that's one really key version of that.

Now, the other reason, right -- so that's why we talk about the pangolin receptor

binding domain, right?

Q Got it. What, if anything, does that indicate about the possibility of passage work using a natural virus, hypothetically in this example the pangolin virus in question, in humanized cells? If you did that work, would that not have the same --

A That would look -- yeah, that would look like this. And I'll come to that argument, because that's an important one, right? I'll come to that. Because that's actually not spelled out in the paper, right?

Q Okay

A But, again, the importance of the pangolin really here is that this feature is natural, right? So the idea that this is a result of a passage thing, it just doesn't hold water. Does it directly disprove the passage? No, it does not. Right? And, again, as we say, we can't prove or disprove anything here, right?

The other reason -- then we mentioned the furin cleavage site, right? The reason why we bring this up is that, in my earlier conversations with Mike Farzan, he had mentioned that, well, when you passage coronaviruses, they have a tendency to pick up furin cleavage sites. Or at least I thought that's what he said to me. And I was like, holy crap, right? This has a furin cleavage site; I think it could've been passage, right? And that totally fits with that.

The thing is, that just isn't true. In fact, the opposite is true. This virus loses the furin cleavage site. We didn't know that at the time, right? We now know that. But Mike had told me -- or I thought he told me this. Maybe he didn't, actually. Maybe I'm just misremembering.

[Thats only in VERO cells Monkey kidney, not in humanized mice with humanized lungs, or human lung cells]

But I spent a long time trying to, like -- what was Mike talking about? What is the reference for him saying that that occurs? And not only could I not find it, the reference I did find showed that, well, if you already have the furin cleavage site and then you passage it, then that virus can grow out. But that's completely different, right? So this idea that I had, like, again, I had with the receptor binding domain, I had with the furin cleavage site, I initially thought that actually these could be the result of passage. But, specifically, what the data show is that, actually, it's not, right?

Q So there's a lot there to unpack. I'm going to try to divide it up.

A Yeah.

Q One is to pivot for a moment away from this.

The more recent information

that postdated this paper but that we've heard about elsewhere and that you just mentioned seems to indicate that the furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2, when passed in culture in, I think, human or humanized cells --

A Well, in provided Vero cells, which are actually green monkey cells.

Q Okay.

A They're primate cells. But this is what's typically used across the field,

including at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Q That, in that situation, the furin cleavage site goes away?

A Yes. It's lost.

Q Coming back to the paper's treatment of furin cleavage site, I just want to

briefly touch on it. There are two components of that.

There is this mention that furin cleavage sites have really only been observed after

prolonged passage with low pathogenicity avian flu viruses; and then, separately, the

point that, to develop furin cleavage site in passage, you would've had to isolate a very,

very similar virus, which nobody has described doing.

A Right. Right.

Q For that first avian flu point -- and I know that different folks maybe had

emphases on different parts of this paper, so to the extent you can speak to it.

A Sure.

Q But is it that that avian flu situation is simply where the development of the

furin cleavage site has previously been observed in passage?

A that -- I'm not actually sure that avian flu can pick it up in tissue culture passage. But it's

the hallmark of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza that they pick up this furin cleavage site as a result of passage through chicken farms, right? I mean, they call it passage. It's

Yeah

And to be perfectly honest, we do mention -- well, I'm not actually sure very rapid transmission through chicken farms. There is this stepwise acquisition of a furin cleavage site as part of that process, which happens, again, in chicken farms. And,

in fact, that's why we mention that we find that, if this is acquired as part of an

intermediate host, it probably requires a dense animal population.

I will say that, while I feel that our conclusions are fully justified, given additional

knowledge, I actually -- we see, for example, that SARS-2 itself picks up parts of human

genes along the way, right, as part of these recombination events. I think it's very likely

that SARS-2 could just have picked up a host gene.

For example, this specific genetic sequence that creates the furin cleavage site is

found in raccoon dogs, right? In fact, we even found it in these samples from the Huanan Seafood Market. There is that very same sequence that is identical to basically

the, quote/unquote, insertion that creates the furin cleavage site in a raccoon dog gene,

right?

So I think, like, some of our conclusions here, I think there are probably other

possibilities that could create the same that wouldn't require, for example, a dense

population of intermediate hosts.

Q Okay. Great.

And then the other -- it's almost mentioned in passing, but with respect to furin

cleavage site, the idea that that would've required isolating a progenitor virus --

A This is the key argument, actually. We should obviously have spelled that out, right? Because this goes back to what I've been talking about, the idea of these viruses trying to spill over into us all the time, versus scientists doing a field trip here and a field trip there and then magically ending up picking up the next pandemic virus, is -- you know, it's like standing in front of a goal, and you have Peter Schmeichel there, and you say, like, okay, I'll give you three tries to score against him, and you're me, not an actual, you know, seasoned football player. You probably can't do it, right? But you're saying, like, okay, let's take the city of San Diego, put them in front of Peter Schmeichel, and then say, okay, you each have 10 tries. It's more likely you will score a goal in that situation.

That's not to say that I couldn't score a goal. Maybe I can, right? But just in terms of prior probabilities, given no other evidence whatsoever, the idea that these scientists go out, picks up the next pandemic virus, takes it back to the lab, actually manages to isolate it -- because that's very hard, right -- accidentally infect themselves, and all of this, as we also describe, being associated with early cases in a wet market, it just doesn't make any sense to me scientifically. Right?

And that's why -- I think why, right -- because, again, it's a consensus sentence, and the paper was written quickly, and did we spent a lot of time on, like, how do we exactly do -- no, we didn't, right? But that's why we say, and we truly believed at the time, is, like, we just don't believe that any of these lab-leak hypotheses are possible.

They're not impossible, right? And we make that clear. We said, we can't prove or disprove anything here, right? Which is the case of all other epidemics and pandemics too, right? But we just, we personally, as experts in this particular field, we just don't find it to be possible.

People can agree and disagree on that, and people certainly have. And they're entitled to, right? That's why you publish the papers.

Q The last major, sort of, topic here from the paper itself is the O-linked glycans.

A Yeah.

Q And, first, just a threshold point. There's discussion about predicted O-linked glycans.

A Yep.

Q If I understand correctly, at the time, they were predicted --

A Yep.

Q -- which means exactly what it sounds like. It has since been, it sounds like, confirmed that --

A I think it's confirmed, yeah. I do think -- we actually predict them here, yeah.

Yeah, I think they're confirmed to indeed be O-linked glycans. I don't think, though, they're mucin shield, as we describe here.

[it should be noted that this prediction was not confirmed by Cryo‐EM inquiry into the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein]

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7744920/#bies202000240-note-0009

Q Well, that's -- so, if you could talk a little bit about the significance of the glycans --

A Yeah. I think the way in which we put significance to it here is that mucin shields are typical ways for viruses to basically shield features that would be recognized by the human immune system, and by putting sugars, glycans, on there, then the immune system can recognize it. HIV, for example, does this constantly, right? And viruses use these mucin shields, so basically you have a lot of these glycans just covering a whole area so it basically can't be recognized. And that's the idea of a mucin shield -- which Ebola, for example, is a very big feature of Ebola.

This is just a few glycans. And this is mostly a comment that Bob introduced, the idea of this mucin shield. And we discussed that, look, it's very few, but maybe it could be. And it's one of Bob's expertise, right?

But I actually think -- I don't think it's a mucin shield. I don't really think that this specifically suggests the presence of an immune system like we describe here. I think it's much more likely that those glycans actually regulate the cleavage of the furin cleavage site itself.

And that's based on -- you know, somebody reached out to me after this paper and saying, like, oh, you know what, that proline that you have in that furin cleavage site, I have done work in, like, grisulphulate (ph) or something like that and have described biochemically how that prolines leading to those glycans actually regulate the cleavage.

And I think that's -- we didn't know that at the time, of course. But I think that's the more likely explanation for what do these glycans actually do.

—————————————————————

Bioweapon, I didn't consider these, right? That doesn't make sense with a novel virus, so it's not that.

But then my evolution on that is that, again, realizing additional things around a furin cleavage site, for example, that it's, in fact, not perfect. It's pretty crappy, right? It appears to be out of frame -- exactly what an engineer wouldn't do. And, of course,

Q And one discrete question, and then one more, and then I'll wrap up. The discrete question, which I forgot to ask about -- the BamHI restriction site.

A. BamH1, yeah. BamH1. That did not even, it seems, make it --Right.-- past --

Q can you explain why that one was knocked out right away?

A Yeah. I think, you know, Eddie referred to us as loons if we even, you know, mentioned that. And the BamH1 stood out -- so BamH1 is one of these molecular scissors I talked about, right? And BamH1 is, in fact, one of the ones they have previously used at theWIV, but -- we see it in SARS-CoV-2. But it's because of a single difference betweenSARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13, for example. It's just because of a single difference between those two that that creates a BamH1 site, which is present in SARS-2 but it's not present in RaTG13.

I should say, actually, that -- because I do remember this, talking about this now -- that I think especially Francis Collins was like, "But that nails it for a lab leak, doesn't it?" And it doesn't, because, again, the difference is so minor. And, in fact,

given, like, the BANAL viruses, for example, they have exactly that restriction enzyme too.So we know it's just totally natural, right?

[BANAL viruses from Laos were published after SARS-Cov-2. How do we know these were not engineered as well but presented as natural to provide cover for Sars-Cov-2]

But it just didn't make sense as an argument, because there was also some conservation around the site that initially had me concerned, which I just realized was -- it was just wrong. There wasn't actual conservation. But it was such a subtle difference, which I describe here, actually, in our early notes, that it just doesn't make any sense. And that's why it didn't make it into the paper.

Q Great. Thank you.

A But we certainly looked at it closely, I will say. It wasn't just BamH1 we looked at, although -- because that's the type of work I've done in the past, is using these molecular scissors to, you know, pluck things in and out of retroviruses, again, as part of my Ph.D. work, right?

So I looked very, very closely at that, saying, like, they use all these different things. Are there any patterns that would be consistent with that? And there just isn't, despite what, you know, some authors have published on

—————————————————————

A Yeah. "Laboratory construct," basically, what we are referring to there is the idea of a chimeric virus, right, like WIV-1 backbone, for example, or some of the laboratory constructs, that we have to create these kinds of viruses from Ralph Baric's work, for example. That's specifically the intended meaning of "laboratory construct."

"Purposefully manipulated virus," the intended meaning of that is the idea that somebody would create SARS 2, with the intent of creating SARS 2 bioweapons, for example, would be that. That's what we mean with a "purposefully manipulated virus.

Q So -- and I'm not saying -- like, I'll get to furin cleavage sites, but -- so would, as kind of Dr. Garry initially suggested, would dropping a furin cleavage site into a novel coronavirus, which category would that fall into?

A Well, it would -- well, kind of both --

Q Okay.

A -- right? Again, the language here is not very precise. I would say engineering could've been mentioned in here too, right? Well, we could just have said engineering.

But the meaning is a little different here because we don't actually specifically talk about engineering, right? We talk about the idea of laboratory constructs and purposefully manipulated viruses.

If you ask me today where would this fall in under, it would fall in under either.

I stated previously there are many reasons why that just does not make

First of all,

It doesn't use the kind of cloning systems or the technologies that are most commonly used from the WIV.

The features themselves appear to be natural features and not engineered features. They're sub optimal. They're not inserted in a way in which you would expect a designer would do.

And those are the basically the reasons why we felt that this is a justified argument, that it just doesn't make sense to think of this as an engineered virus.

Q. Back to Dr. Fouchier, who says, molecular biologists like myself can generate perfect copies of viruses without leaving a trace. The arguments for and against passaging and engineering are the same if you ask me.

What does this mean?

A So this means that there are seamless cloning technologies which, quote/unquote, do not leave scars in their -- in the viral genome, and molecular biologists are capable of creating such things. Ralph Baric developed many of these technologies, for example. He, himself, argues against this was being done here, right?

But the reason why we feel that it just doesn't make sense is for the same reason that I just mentioned, right, is that it's not the technologies that they're very commonly using, and the virus itself looks to be -- again, the features that are, quote/unquote, special to this virus, look evolved, not engineered.

And so that's the reason, and that's the reason why I disagree with Ron on this point because I actually do think it's important to distinguish them. And I think most people would agree that we should distinguish engineering from passage, whether that in animals or tissue culture, yeah.

————————————————————-

Q And we've touched on the next couple a little bit, but I want to ask again.

Is there a way to tell if a virus gains a furin site through natural evolution versus laboratory passage?

A I mean, again, there would be certain -- again, if you insert the site into the virus, which has been done for all the viruses, including coronaviruses, then typically people use what we know to be a good furin cleavage site.

There are multiple versions of a furin cleavage site, right? There's optimal ones and there's sub optimal ones. And when research have done this in the past, they do with, like, we know that this is an optimal furin cleavage site. We know it will definitely be cleaved by furin. That's what people insert.

This is not that, right? It's a sub optimal site. It is good enough to be cleaved by furin, but it's not a great site and, in fact, has since evolved to become a beta site in things like Omicron and alpha and other variants, right.

Q Beyond just inserting it --is it possible, or has it been done before -- two separate questions -- to gain it in a coronavirus just through either culture or animal passage?

A I don't believe so. So, again, this is where, you know, my early thinking was this, that I thought it was possible, but I just think that -- because, again, I've looked, you know, everywhere for a reference that would suggest that it can be gained during passage, for example, and I just haven't found anything.

And, again, what's important here for SARS 2, specifically we know that it has a tendency to actually lose it as its passage in tissue culture.

[Only with Vero Cells]

The furin cleavage site itself probably makes the virus less stable, and that's probably detrimental in tissue culture. And that means that if there is a version of the virus that emerges in this tissue culture experiment that doesn't have the furin cleavage site, then they'll out-compete all the other viruses in the same cell, and very quickly you'll end up with basically having viruses that -- viral particles that don't have that furin group, so --

The fact that it even loses it is interesting because -- and it probably has to do with the fact that furin cleavage sites are probably important for respiratory transmission of a virus, which is probably also why they're pretty rare in bats, right, because bats don't transmit viruses between themselves in the respiratory route. They do this with the good old fecal-oral route.

And that's different than that in mammals. That's why a lot of coronaviruses in rodents, for example, have furin cleavage sites because that's a respiratory route. In bats it's not a respiratory route, so there the furin cleavage sites are rarer, although still present.

[So you would passage the virus in rodents or mice with humanized lungs and not Vero Cells]

Q It's an email chain with yourself, Dr. Holmes, Dr. Rambaut, and Dr. Garry, and Bates-numbered GARRY0000098 through 104, and I want to go to the page marked 100. And right in the middle of the page is a long email from Dr. Garry, and at the bottom, he says, Bottom line, I think that if you put selection pressure on a coronavirus without a furin cleavage site in cell culture, you could well generate a furin cleavage site after a number of passages. But let's see the data, Ron. It will infect a lot better if it can effectively fuse at the cell surface and doesn't have to rely on endosomal cleavage and receptor-mediated endocytosis?

A Yeah.

Q Do you agree with that statement, that you could put enough pressure on a coronavirus to generate a furin cleavage site?

A I think as a -- as a hypothesis, I think it's a good hypothesis. I mean, again, this is basically akin to what I was saying at the time, especially -- and I can't remember if I put that in an email or just mentioned it in conversation, but typically these are passaged in the presence of trypsin, which is an enzyme that will cause that cleavage to happen in the absence of a furin cleavage site.

It's, in fact, I think -- I believe it's required for, like, passaging SARS 1. And so my idea, which is similar to what Bob is saying here, is that if you did that experiment in the absence of trypsin, you would probably select for a virus that would have a furin cleavage site.

The problem is just that it's just wrong, right. For SARS 2 specifically, it doesn't gain it, it loses it, right? And while it's a good hypothesis, as Bob says, but "Let's see the data, Ron" -- I actually think it's Mike that this -- this idea comes from. I don't think Ron said that it could -- that furin cleavage sites could happen in tissue culture.

[this guy is intentionally misleading. If you wanted to puck up a FCS you do so in cells where it wont lose a FCS like human lung cells]

—————————————————————

Q Is it like --your opinion about the source of the virus because of a $9 million grant. Would you like to respond to that?

A. Yeah. I'll say those allegations are, of course, false. There's no connection between, for example, the drafting of proximal origin and the CREID grant that we received in 2020. That grant was written in June or submitted, applied for, in June of 2019, was reviewed and scored in November 2019, prior to the pandemic, with counsel at the NIH, in which they make funding decisions in January 2020, prior to any of the events leading, for example, to the February 1 conference call.

[CREID was not formally approved or announced until mid -2020 so no grant could be official until then, no matter what preliminary or informal approval was given. Its like dangling a carrot in front of a rabbit. If you hop just right you can have it, otherwise it gets pulled away]

And there is no way in which funding of a grant -- this particular grant, I'm the PI on that, as we've already discussed, co-PIs, both Dr. Garry and Dr. Sabeti, with collaborators in West Africa through four different countries. But, of course, there is no connection between the publications of papers and the award of that grant.

It's simply an example of experts in emerging infectious diseases, studying emerging infectious diseases, get awarded a grant on emerging infectious diseases, and to continue that work with West Africa.

GARRY

There are other things that the genetics of the virus can tell us. Okay. There are actually two lineages of the virus that were present in Wuhan early in the pandemic. This is the Pekar et al paper. Those lineages are called lineage A and lineage B. Okay. So both of those lineages, it turns out, were present in those environmental samples at the market. This is really deep down into the, you know, the phylogeny of this virus early on. And I won't go through the details. We can go through Pekar et al if you'd like, but basically what we know is, is that lineage B spilled over first in the market, okay, in the market. Okay. Because most of those early cases in the market were of this lineage B virus. But there's a lineage A virus there, too. And the particular importance of lineage A is that that lineage is closer to the original bat coronaviruses.

Okay.

There's several mutations that make us believe that that is deeper in the phylogeny than lineage B viruses. But the analysis there that we did in Pekar et al showed that the lineage A virus spilled over second, a week, 2 weeks later in the market.

So, if your scenario is that somehow or other somebody from the lab introduced that, then you have to think, okay, they introduced it twice because if they had introduced, you know, -- the only really -- the only logical way to explain this is that the virus was in the animals that were in the market. They were lineage A and lineage B viruses. It doesn't make any sense to think that a human introduced that based on that analysis of the phylogeny.

[Lineage A (Team A) wasn’t getting the results they hoped for so they went to their Team B Virus]

Q Okay. Under the ones that did involve collecting sequencing viruses, were the sequences published?

A You know, we haven't gotten quite that far. I'm talking about this Centers for Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases grant. And we got a little sidetracked with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic to actually go out and try to find some new ones, so --

Q In your experience with grants, if the grant application is denied by the Federal Government, are there other avenues for funding?

A Sure.

Q And in your experience, is it common for an organization to begin some of proposed prior to submission of a grant proposal?

A It is.

Q Why is that?

A You need plenary results to usually run the application. You have to that you have, you know, the capability, the experience, the track record to do the experiments that you're proposing. And one good way to do that is to show them that you've already done some similar experiments. So, yeah.

Q Are you aware of the proposal submitted to DARPA, the defused proposal that was denied?

A I'm aware of it in general terms, yeah.

Q Was there a proposal to insert furin cleavage sites into these background viruses?

A I've seen that paragraph and I've read it because it's, you know, been the topic of a lot of discussion. So the answer to your question is yes.

Q Where was that work proposed to take place?

A At the University of North Carolina.

Q Was the Wuhan Institute of Virology a proposed collaborator on that grant?

A They were.

Q Would the University of North Carolina not tell the Wuhan Institute of

Virology that they were doing that work?

A I don't know. It's speculation.

————————-

A Okay. So the idea if you're, you know, looking at the possibility of modifying a virus in the lab, requires that you have something that's close, okay. I mean, the genome of SARS-CoV-2 is about 30,000 nucleotides. Those bases, A, T, C, U. And then -- A, U, C -- never mind this one. Okay. So it's 30,000 nucleotides to deal with

And so, you know, the closest virus we know about now is a virus called Bengal 2052 (sic BANAL 52 from Laos). It's about 96.8 percent similar to SARS-CoV-2. That's about a thousand of those nucleotides different.

So, you know, the laboratory and that you were hypothesizing may have created SARS-CoV-2 in the lab, would have had to have had a virus that was much closer than that, much closer than any of the viruses that we even know about now, to get from, you know, this hypothetical virus to SARS-CoV-2.

Nobody's going to be able to sit down in, you know, a lab with, you know, a virus that's only 97 percent similar and design it in a way that you could get to, you know, such a, you know, very efficient pathogen with SARS-CoV-2.

Q There -- can you just talk a little bit why you would expect somebody doing that kind of hypothetical work to use a known published backbone?

A It -- you know, it just comes down to, you know, you work -- you know, the scientists in the laboratory are trying to figure out about how these viruses replicate and, you know, what their features are that make them do what they do, you know, make them transmissible, make them pathogenic. The idea that you'd spend a whole lot of time on just some random virus from a bat doesn't really make much sense from a scientific standpoint, you know. It's not something that's very likely at all. In fact, it's very unlikely to give you any very -- any useful information.

Why would you just -- you know, there are millions of viruses out there, literally more than that. You know, just picking one and saying, okay, we're going to do this, kind of very detailed, intense, expensive kind of work on it really doesn't make any sense.

Most virologists, if they're studying viral pathogenesis, will at least start from something that's sort of known, that we know that this virus, for example, or one of its relatives causes an important human disease.