The following comes from the below sources and various mainstream stories. Question Everything

Unlimitedhangout.com. whitney webb

Dark Towers -Deutsche Bank, Enrich

House of Trump, House of Putin, Unge

Trump Nation, O’Brien

Ordo ab Chao Volume Six: The Third Temple , Livingstone

Red Mafiya: How the Russian Mob Has Invaded America, Friedman

The focus here is not on Events during Trumps Presidency. That can be found here

There is some redundancy as this is quite long and there are so many connections it may help to repeat some of them

2000 Deutsche bank had plunked down another $150 million to be used for the renovations of Trump’s building at 40Wall Street.

The next year, Deutsche agreed to extend Trump a mortgage worth more than$900 million—at the time,the largest ever on a single property—so he could buy the General Motors Building on the southeastern corner of New York’s Central Park. (Trump already owned half of the fifty-story building; he wanted the rest.)

2000-Deripaska’s principle advisor is Nathaniel Rothschild, son of the current Baron of the family, Lord Jacob Rothschild. Nathaniel played a crucial role in 2000, when Deripaska and Roman Abramovich created a partnership and founded RUSAL, the largest aluminum company in the world.

In 2001, about a year after Putin signed a decree granting legal immunity to Yeltsin’s family, Deripaska married Yeltsin’s granddaughter, thereby cementing his own immunity and influence.

-Abramovich is the primary owner of the private investment company, Millhouse LLC and is best known outside Russia as the owner of Chelsea Football Club, a Premier League football club.

In their 2004 biography of Abramovich, the British journalists Chris Hutchins and Dominic Midgely describe the relationship between Putin and Abramovich as like that between a father and a favorite son.

Abramovich was the first person to originally recommend to Yeltsin that Putin be his successor. Abramovich and fellow oligarch Lev Leviev would go on to become Chabad Lubavitch’s biggest patrons worldwide.

2000-The case against Browder and the other investors was eventually settled in February for an undisclosed amount along with an agreement that Browder et al would sell their VSMPO shares.

Two years later Harvard Business school did a case study on Hermitage Capital and you want to know what Browder said to them about Avisma?

“The worst thing that has happened to me is when we resolved an asset-stripping dispute by seizing money offshore, which had been taken by the corrupt managment. Instead of admitting defeat the people who organized the asset stripping launched a racketerring lawsuit against me in the U.S. Imagine this, a bunch of Russian crooks accusing me of rackettering. Of course the case was dismissed.”

Of course the case was dismissed?

This guy is as fundamentally incapable of telling the truth as Hillary Clinton. Seriously. As of today, even Avisma’s attorneys have on the front page of their website a blurb about the case which reads, “The case was resolved with a favorable settlement for plaintiff.”

2000-Wilbur Ross went into private equity in , forming WL Ross & Co. He still runs it, but he sold it to investment firm Invesco in 2006 for some $375 million. In 2013 Invesco partnered with Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and others to buy 5 industrial properties from the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Brooklyn for $240 million.

Nearly all of Trump’s wealth is tied up in real estate, but he has also owned stocks. One holding, according to a May 2016 filing: $250,000-$500,000 worth of Invesco European Growth Fund Class Y shares. (Trump claims to have sold his stock holdings in June, though he has not provided evidence to support the claim.)

Trump and Ross are also neighbors in both Florida and New York. Not only is Ross’ 16,000-square-foot home just up the road from Trump’s 126-room Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, but the two also share a 57th-Street address in Manhattan. Ross’ penthouse is just two blocks from the president-elect’s Trump Tower triplex.

For those seeking influence in Washington, the president’s cabinet is the highest echelon. While concerns about potential conflicts of interest mount, one person who will have the Commander-in-Chief’s ear is his billionaire pal Ross. Will Trump and Ross’ latest deal be good for America’s balance sheets, or their own?

2000-Deutsche bank CEO Edson dies-in plane crash in December

2000-One of Kroll’s directors, Jerome Hauer, managed New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s Office of Emergency Management, which he had located on the 23rd floor of WTC 7 in 2000.

2001-Two years after Rolf Breuer’s lie about not being engaged in ubernahmegesprache with Bankers Trust, his deception threatened to come back to haunt the bank.

The Securities and Exchange Commission opened an investigation, and by March 2001, its enforcement division had reached a preliminary conclusion: Deutsche and Breuer himself should be punished for misleading investors.

The SEC’s head of enforcement at the time was Dick Walker, a permanently tanned,perfectly bald lawyer.A few months after his staff recommended taking action against Deutsche and Breuer, Walker made a surprising announcement: He was recusing himself from the case. Two weeks after that, the SEC—seemingly out of nowhere—informed the bank that ithad decided to close the investigation without any punishment.

And three months after that,in October 2001, Walker announced that he was taking a job as a general counsel at Deutsche. “Dick Walker probably knows more than anyone about U.S. securities laws and regulations,” a top Deutsche executive enthused.

Not long after, Walker hired Robert Khuzami, a federal prosecutor with a specialty in complex securities fraud cases,to join Deutsche and help shield it from government investigations.

Deutsche had discovered the power of the “revolving door”— the process of luring government watchdogs to the private sector—to neuter investigations.*

2001-Deutsche’s forty-floor Manhattan headquarters which had been the offices of BankersTrust—was right next to the World Trade Center. When the plane flew into the South Tower, some 1,500 windows were shattered in Deutsche’s building. When the towers fell,flying metal and concrete ripped a deep,fifteen story gash in the side of the building.

What used to be its entrance was now a smoldering heap of wreckage, with

shards of the World Trade Center’s grill-like facade embedded in the walls. Miraculously, only one Deutsche employee died.

Deutsche was planning to list its shares on a U.S. stock exchange for the first time. Much was riding on them being easily tradable in America, too.

In the privacy of his art-adorned fiftieth-floor condo in a skyscraper adjoining the Museum of Modern Art, Ackermann and his colleagues had secretly been plotting potential mergers with various U.S.banks, including JPMorgan, to transform Deutsche into a true global leviathan. To conserve cash, the proposed deals would take place mostly by swapping shares of Deutsche and its merger partner. That meant Deutsche’s stock needed to be publicly listed in the United States.

The New York Stock Exchange reopened a week after 9/11, and on October 3, Deutsche’s shares debuted, trading under the ticker symbol DB.I

Deutsche’s downtown building was ruined. Executives from Europe came to survey the wreckage and, wearing gas masks, encountered a horrific scene. Human body parts—the mangled remains of World Trade Center workers and first responders— littered the basement. The building was beyond repair.

But because it was filled with dangerous slevels of mercury,asbestos, toxic mold, and other nasty stuff, there was no way to dismantle it without spreading more poison in Lower Manhattan. So the shell of the doomed tower was draped in a veil of dark webbing, an enormous tombstone towering over the hallowed Ground Zero.

There it sat for years , ghostly,impenetrable reminder not only of 9/11 but also of the lethal mess that would soon lurk within one of the world’s biggest banks.

2001-The Enron Corporation was collapsing and this was formally announced in late 2001 amidst allegations of fraudulent accounting. They hired Kroll Zolfo Cooper to handle its chapter 11 proceedings. Many SEC and FBI records on Enron were likely lost in the WTC7 collapse

Greenberg's son, Jeffrey W. Greenberg, became CEO of Marsh & McLennan (MMC) in 1999 and chairman in 2000. The first plane of 9-11 flew directly into the secure computer room of Marsh (Kroll) USA, part of Greenberg's company.

In mid-October 2001, The Independent (UK) reported that, “To the embarrassment of investigators, it has….emerged that the firm used to buy many of the ‘put’ options (where a trader, in effect, bets on a share price fall) on United Airlines stock was headed until 1998 by Alvin ‘Buzzy’ Krongard, now executive director of the CIA.”

2001-According to the New York Times, Mayo Shattuck III “was made co-head of investment banking in January [2001], overseeing Deutsche Bank’s 400 brokers who cater to wealthy clients.” It is curious that Shattuck resigned immediately after the 9/11 attacks.

2001- Kroll controlled security at the World Trade Center complex through 2001 and was responsible for hiring John O'Neill, the former chief of counterterrorism for the FBI, an expert on Osama Bin Laden and Al Qaeda who was stopped from pursuing the USS Cole investigation, and who died on 9-11, reportedly his first day on the new job.

2001-allegations that Trump entered the Miss Teen USA changing room where girls as young as 15 were in various states of undress.

Mariah Billado, Miss Teen Vermont 1997 told BuzzFeed, “I remember putting on my dress really quick because I was like, ‘Oh my god, there’s a man in here.'” Three other teenage contestants from the same year confirmed the story.

The former pageant contestants discussed their memories of the incident after former Miss Arizona Tasha Dixon told Los Angeles’ CBS affiliate that Trump entered the Miss USA dressing room in 2001 when she was a contestant.

The same year former contestants say Trump unexpectedly entered the Miss Teen USA dressing room, the reigning Miss Universe, Brook Antoinette Mahealani Lee, recalls Trump asking her about the looks of his 16 yo daughter Ivanka, who was co-hosting the pageant. “‘Don’t you think my daughter’s hot? She’s hot, right?'” Mahealani Lee recalls Trump saying.

Trump denied all allegations

2002, Deutsche agreed to refinance about $70 million that Trump owed on some of his Atlantic City casinos. Those loans came out of Deutsche’s commercial real estate division,

which Kennedy was helping to run. Kennedy was the son of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy

2002-Epstein was associated with both Bill Richardson, former ambassador to the UN and former secretary of energy under Clinton, and Larry Summers, secretary of the treasury under Clinton. Both Richardson and Summers sit on the advisory board of controversial energy company Genie Energy, alongside CIA director under Clinton, James Woolsey; Roy Cohn associate and media mogul, Rupert Murdoch; Mega Group member Michael Steinhardt; and Lord Jacob Rothschild.

Genie Energy is controversial primarily for its exclusive rights to drill in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

Bill Richardson appears to be among the Clinton era officials closest to Jeffrey Epstein, having personally visited Epstein’s New Mexico ranch and been the recipient of Epstein donations of $50,000 to his 2002 and 2006 gubernatorial campaigns.

Richardson gave Epstein’s donation in 2006 to charity after allegations against Epstein were made public. Richardson was also accused in recently released court documents of engaging in sex with Epstein’s underage victims, an allegation that he has denied.

2002-It starts with Bayrock . This is the company that Donald Trump teamed up with to build his Trump Soho project. There were three main actors . One was convicted mob associate and FBI informant Felix Sater. Another was Tevfik Arif, a likely Russian intelligence connection who was once was arrested by the Turks . The third was the late Tamir Sapir, another man with ties to Russian intelligence.

The late billionaire Tamir Sapir, was born in the Soviet state of Georgia .

Trump has called Sapir “a great friend.”

It was Sapir who introduced Trump to Tevfik Arif, the founder of Bayrock, aka Tofik Arifov.

In December 2007, he hosted the wedding of Sapir’s daughter, Zina, at Mar-a-Lago. The groom, Rotem Rosen, was the CEO of the American branch of Africa Israel, the Putin oligarch Leviev’s holding company, and known as Leviev’s right hand man.

As mentioned Leviev was one of two oligarch’s who Putin had establish the “Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia under the leadership of Chabad rabbi Berel Lazar, who would come to be known as ‘Putin’s rabbi.'” Sater, Sapier, Jared, Ivanka are all Chabad members and/or donors

Bayrock through its business practices brought into Donald Trump’s orbit a host of oligarchs and alleged mobsters involved in laundering money, the trafficking of underage women, feeding intelligence to the Russians, and more.

In court records from a lawsuit by former employees, it is alleged Bayrock was “covertly mob-owned and operated,” “backed by oligarchs and money [the oligarchs] stole from the Russian people,” and “engaged in the businesses of financial institution fraud, tax fraud, partnership fraud, human trafficking, child prostitution, statutory rape, and, on occasion, real estate.”

On paper, at least, Arif’s story was another stirring rags-to-riches saga. Tevfik Arif, born in Kazakhstan during the Soviet era, was a state-employed economist who turned to hotel development in Turkey in the 1990s before moving into New York property development where he founded Bayrock in 2001.

In 2002, after becoming a successful real estate developer in Brooklyn, he moved Bayrock’s offices to Trump Tower, where he and his staff of mostly Russian émigrés set up shop on the twenty-fourth floor.

When Arif and Sater helped put together several prospective Trump Tower licensing deals for sites including Moscow, Warsaw, Istanbul, and Kiev, Trump was ecstatic.

Thanks to Bayrock, he could bring franchising to high-end condos. He could be the Colonel Sanders of luxury high-rises. “It was almost like mass production of a car,” Trump crowed. For some projects, he boasted, he would get up to a 25 percent stake, plus management fees and a possible percentage of the gross—without having to invest a dime.

Trump worked closely with Bayrock on real estate ventures in Russia, Ukraine, and Poland. When it came to financing them, however, he was still so toxic after Atlantic City that he left matters of funding to his new partners.

“Bayrock knew the investors,” he later testified. Arif “brought the people up from Moscow to meet with [Trump].” Altogether, Bayrock’s leadership, as portrayed in its presentation materials, was a cozy family of billionaire oligarchs from the former Soviet Union.

In fact, the extent to which various Bayrock partners actually came through with financing is unclear, but according to Bayrock’s promotional literature, Arif turned to fellow Kazakh billionaire Alexander Mashkevich and his Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (or Eurasian Group, as it is called in Bayrock’s promotional literature), which he controls with Patokh Chodiev and Alijan Ibragimov, among others, to finance Bayrock. (Even though he was referred to on Bayrock’s website, Patokh Chodiev has denied any connection to Donald Trump, the Trump Organization, or Bayrock Group. Similarly, a person close to Mashkevich told Bloomberg that Mashkevich never invested in Bayrock.)

Together, the three men—known as “the Trio”—are major stockholders in the Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation and control chromium, alumina, and gas operations in Kazakhstan, which adds up to about 12 percent of the industrial production in the entire country.

Another Bayrock partner, the Sapir Organization, had, through its principal, oligarch Tamir Sapir, a long business relationship with Semyon Kislin, the Ukranian billionare commodities trader who was tied to the Chernoy brothers and, according to the FBI, to Vyacheslav Ivankov’s Russian mafias gang in Brighton Beach.

In June 2005, many of them came together when Arif celebrated his fifty-second birthday at the grand opening of the “seven-star” Rixos hotel in Belek on the Turkish Riviera near Antalya. Guests came from all over the world—St. Petersburg, the Côte d’Azur, Ukraine, Latvia, Israel, and Moscow, traveling by yacht and private jet.

This was no run-of-the mill gathering. There were huge mounds of caviar, food, drink, and song. Among the honored guests was then–prime minister of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who later became president. There were professional hockey stars, Moscow restaurateurs, and billionaires from all over the world. In all, Bayrock’s promotional literature boasted that it had seven billionaires affiliated with the company, in one way or another.

Among them was Tamir Sapir, who arrived on the Mystère, his 160-foot yacht, which has been described as the most beautiful private vessel in the world. Alexander Mashkevich cruised in on his yacht, the Lady Lara, which was nearly twice as big, at 299 feet.

Not all the Bayrock billionaires could make it, but one extremely high-profile tycoon in New York who couldn’t attend made sure that his presence was felt anyway. So on Tevfik Arif’s birthday, the familiar image of Donald Trump suddenly appeared on a big-screen videoconference call for the entire party to see.

By this time, Trump was indeed in the midst of a phoenix-like rebirth, both personally and professionally. His turbulent tabloid marriage to Marla Maples, his second wife, had come to an end, and he had married his third wife, Melania Knauss, a model from Slovenia, in January 2005, in a suitably extravagant wedding on his Mar-a-Lago estate that was attended by celebrities including Shaquille O’Neal and P. Diddy, then-senator Hillary Clinton, and former president Bill Clinton.

And when it came to real estate, Trump’s new paradigm was taking off like wildfire. He was all over Bayrock’s promotional literature, but he had nothing to do with financing and few development responsibilities.

The larger point was that Trump had created a new model where he was paid to put his name on major development projects. “He’s a marketing genius,” Adam Rose, president of Rose Associates, which manages more than fourteen thousand apartments, told the New York Times. “He’s gotten to the point where he can license his name.”

And license he did, lending his name to projects like Trump University, a “real estate training program” that turned out to be not a university at all but a gigantic high-pressure bait-and-switch scam* that “preyed upon the elderly and uneducated to separate them from their money,” as one affidavit from a former salesman for Trump University put it.

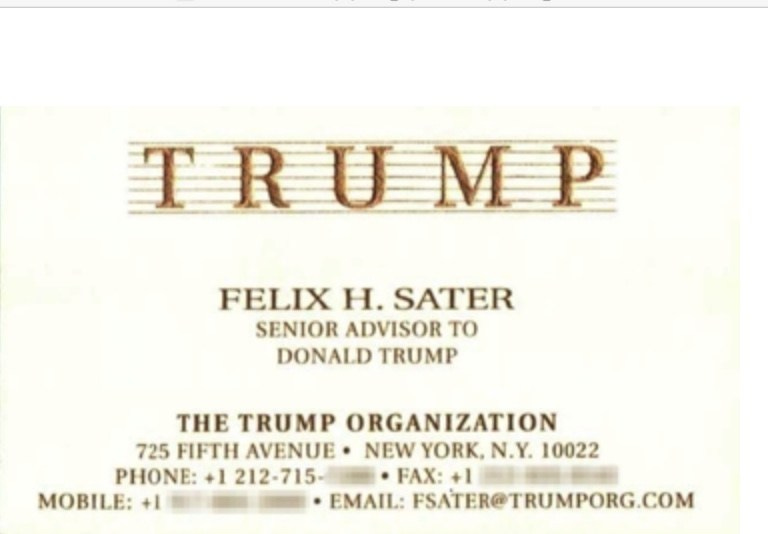

Felix Sater, the senior Bayrock executive who worked at Bayrock from 2002 to 2008 and negotiated several important deals with the Trump Organization and other investors. When Trump was asked who at Bayrock had brought him the Fort Lauderdale project in the 2013 deposition cited above, he replied: “It could have been Felix Sater, it could have been—I really don’t know who it might have been, but somebody from Bayrock.”

Although Sater left Bayrock in 2008, by 2010 he was reportedly back in Trump Tower as a “senior advisor” to the Trump Organization—at least on his business card—with his own office in the building.

Sater has also testified under oath that he had escorted Donald Trump, Jr. and Ivanka Trump around Moscow in 2006, had met frequently with Donald over several years, and had once flown with him to Colorado. And although this might easily have been staged, he is also reported to have visited Trump Tower in July 2016 and made a personal $5,400 contribution to Trump’s campaign.

Whatever Felix Sater has been up to recently, the key point is that by 2002, at the latest, Arif decided to hire him as Bayrock’s COO and managing director.

This was despite the fact that by then Felix had already compiled an astonishing track record as a professional criminal, with multiple felony pleas and convictions, extensive connections to organized crime, and—the ultimate prize—a virtual “get out of jail free card,” based on an informant relationship with the FBI and the CIA that is vaguely reminiscent of Whitey Bulger.

In any case, between 2002 and 2008, when Felix Sater finally left Bayrock LLC, and well beyond, his ability to avoid jail and conceal his criminal roots enabled him to enjoy a lucrative new career as Bayrock’s chief operating officer. In that position, he was in charge of negotiating aggressive property deals all over the planet, even while—according to lawsuits by former Bayrock investors—engaging in still more financial fraud. The only apparent difference was that he changed his name from “Sater” to “Satter.”

In the 2013 deposition cited earlier, Trump went on to say “I don’t see Felix as being a member of the Mafia.” Asked if he had any evidence for this claim, Trump conceded“I have none.”

2003, the Renova Group, along with Access Industries(owned by Leonard Blavatnik) and the Alfa Group(owned by Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, and Alexei Kuzmichov) announced the creation of a strategic partnership to jointly hold their oil assets in Russia and Ukraine, forming the AAR consortium. In the same year, they merged AAR with British Petroleum's Russian oil assets in a 50-50 joint venture named TNK-BP, the largest private transaction in Russian history.

Acting as a chairman of the executive board of TNK, Vekselberg was instrumental in negotiating and closing the transaction.

2003, another arm of Deutsche, focused on helping companies raise money by selling stocks and bonds to investors, agreed to work with Trump. The point man on this part ofthe relationship was Richard Byrne—another Merrill veteran who had been involved in the Taj Mahal debacle.(Byrne had helped sell the ill- fated Taj bonds to investors.)

Now Trump hired Byrne’s group at Deutsche to issue bonds for his troubled Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts. Byrne knew this would be an uphill battle; not only had Trump defaulted in the past,but he also had recently been taunting investors that he might stop paying back other outstanding bonds.

Waugh didn’t warn Byrne about the recently rejected $500 million loan, and Byrne organized a “road show” for Trump to meet with and try to win over big institutional investors.

He escorted Trump to meetings all over New York and Boston. At every stop, boardrooms and auditoriums were jammed with traders, fund managers, senior executives, and secretaries curious to see The Donald Show, and Trump didn’t disappoint. He rocked, he rolled,and he delivered wildly optimistic and inconsistent financial projections.

Afterward, Trump called Byrne to ask how much money they had raised. The answer, alas, was virtually zero. Byrne braced for an explosion as he explained to Trump that even though he’d been treated like a celebrity, nobody trusted him with their money.

Trump took the rejection in stride. “Let me talk to your salespeople,” he requested. Byrne agreed, and Trump came to deliver a pep talk. “Fellas, I know this isn’t the easiest thing you’ve had to sell,” he acknowledged. “But if you get this done you’ll all be my guests at Mar-a-Lago.”

Trump was always good at pushing an audience’s buttons—a weekend with Trump at Mar-a-Lago: bragging rights that not even money could buy— and this new incentive did the trick. The salesmen worked the phones, cast a wider net for more clients, and managed to sell an impressive $485 million of junk bonds (albeit at a high interest rate that reflected investors’ fears that Trump might default).

When the sale was complete,Byrne delivered the good news to Trump, who was pumped. “Don’t forget what you promised our guys,” Byrne nudged his happy client. “What’s that?” Trump asked. Byrne reminded him about the Mar-a-Lago trip. “No way they’ll remember that,” Trump weaseled.

“That’s all they’ve talked about the past week,” Byrne responded.

Trump ultimately dispatched his private Boeing727 to fly fifteen salesmen down to PalmBeach,Florida. Duringthe day, they golfed. Trump, decked out in white polyester, impressed the bankers with his brazen cheating. At night, they dined at Mar-a-Lago, and Trump regaled them with story after preposterous story about his hijinks with casinos, real estate, Wall Street, and women.

The following year, with his casinos on the rocks, Trump’s company stopped paying interest on the bonds and filed for bankruptcy protection. (“I don’t think it’s a failure; it’s a success,” Trump spun.)

Deutsche’s clients, the ones who had recently bought the junk bonds, suffered painful losses. Going forward, Trump would be off-limits for Byrne’s division.

2003-A year after Trump World Tower opened in 2002, Trump had agreed to let Miami father-and-son developers Gil and Michael Dezer use his name on the condominium towers, which attracted Russians moneny. “Russians love the Trump brand,” Dezer told Bloomberg.

Trump Tower in New York as well has received press attention for including among its many residents, tax-dodgers, bribers, arms dealers, convicted cocaine traffickers, and corrupt former FIFA officials. A typical example involves an illegal gambling operation that reportedly took up the entire 51st floor, run by the alleged Russian mobster Anatoly Golubchik, and Vadim Trincher, a dual citizen of the United States and Israel, as well as Trincher’s son Illya, and Hillel Nahmad, the son of a billionaire art dealer and heir of a descendant of a Jewish Lebanese art family, and another follower of Chabad-Lubavitch.

“This is the top of the top of the top in organized crime in Russia,” according to the prosecutor. The ring answered to Russian mob boss Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov, whose organization the Interpol believes to be tied to Semion Mogilevich.

Tokhtakhounov, who holds both Russian and Israeli citizenship, is one of the world’s most notorious Russian mafia bosses, known as “Little Taiwanese.”

In 2008, Forbes named him the world’s third most wanted, after Osama bin Laden and el Chapo. He is accused of the bribing of judges in the 2002 Winter Olympics, in which a Canadian figure-skating team were denied their gold medal.

Seven months after he was busted in 2013, he appeared near Trump in the VIP section of the Miss Universe pageant in Moscow. Tokhtakhounov operated out of Trump Tower, just three floors down from Trump’s penthouse, what prosecutors called “an international gambling business that catered to oligarchs residing in the former Soviet Union and throughout the world.”

2004-Trump produced and starred in the reality series The Apprentice from 2004, which allowed him to depict himself as the ultimate businessman. Long before his run for president, Trump knew the power of TV: popping up on the small screen as a wildly successful tycoon who had earned his arrogance – and making these appearances repeatedly – made him more relevant to many Americans than any journalistic report about his actual triumphs and failures ever could.

His multiple bankruptcies and tarnished reputation among those who knew or dealt with him in real life didn’t matter. One rare negative depiction on TV was Sesame Street’s 2005 parody, Donald Grump, a character who bragged, “I’m the trashiest!”

JFK was the first TV-ready US president, but Trump is the first TV-star president

Trump dabbled in movies as well: there were cameos in Home Alone 2 and The Little Rascals, and the bullying Back to the Future character named Biff was based on him.

But TV made ‘The Donald’. Before social media, TV was the best way to truly connect with a mass audience. And his carefully crafted appearances show that he was more interested in – and better at – moulding public opinion of himself than perhaps anything else.

Trump told the Washington Post that he ignored the advice of his agent when he signed on to host The Apprentice in 2004. The show, which premiered when reality TV fever was at its height, was a genuine smash its first few seasons, with 20 million viewers watching in the first year. The Post says that Trump realised the series’ potential to reach a younger audience and that he insisted on inserting his name into the production as much as possible: for instance, in the copious shots of his private plane, "TRUMP" emblazoned across its side.

The Apprentice was such a ratings success that network NBC asked Trump to poke fun of his wealth by singing the Green Acres theme at the 2006 Emmy Awards (Credit: NBC Universal)

He also negotiated a 50% ownership stake in the show, and his first-season turn changed TV network NBC’s plan to rotate the host – other moguls like Richard Branson and Martha Stewart were slated to appear in future seasons – so that The Apprentice became a one-man show. (A later Stewart spinoff fizzled quickly.)

Trump’s catchphrase – "You’re fired!" – made him into the ultimate reality show truth-teller. He was Simon Cowell with a very American twist, a message that pointed criticism makes US businesses, and thus America as a whole, stronger, and that hard work is rewarded.

The Apprentice transformed him from a New York City tabloid figure into a TV star recognised in the heart of the Midwest – which would become key territory in his presidential campaign.

Apprentice producer Bill Pruitt expressed regret for having gilded the businessman’s image for the viewing public. He explained in an email to Vanity Fair that with the show, “some clever producers were putting forth a manufactured story about a billionaire whose empire was, in actuality, crumbling at the very same time he took the job, the salary, and ownership rights to do a reality show. The Apprentice was a scam put forth to the public in exchange for ratings. We were ‘entertaining,’ and the story about Donald Trump and his stature fell into some bizarre public record as ‘truth.’”

2004-The friendship between Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein appeared, in public, to be quite sound, as far as Trump acquaintances go. (The loyalty-obsessed president has said that his only “real friends” are family members.)

Beginning in the late ’80s, Epstein and Trump hit it off, as shown in the recently unearthed footage of the two of them ogling NFL cheerleaders together at Mar-a-Lago in 1992. They were photographed together in 1992, 1997, and in 2000, with Trump’s then-girlfriend Melania Knauss.

According to Epstein’s brother, Trump also hitched a ride from Florida to New York on Epstein’s private plane sometime around the new millennium.

Then there’s that 2002 quote Trump gave to New York: “I’ve known Jeff for fifteen years. Terrific guy. He’s a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side. No doubt about it — Jeffrey enjoys his social life.”

But according to a new report from the Washington Post, in 2004, the pair let a mansion called the House of Friendship tear them apart. Bidding on Maison de l’Amitie in Palm Beach, both Trump and Epstein really wanted to win the oceanfront property being sold out of bankruptcy.

The trustee in the case, Joseph Luzinski, told the Post of the process: “It was something like, Donald saying, ‘You don’t want to do a deal with him, he doesn’t have the money,’ while Epstein was saying: ‘Donald is all talk. He doesn’t have the money.’ They both really wanted it.” Around that time, Trump banned the financier from Mar-a-Lago without giving an explanation.

In November 2004, The Apprentice host said he was fixated on winning “the finest piece of land in Florida and probably the U.S.,” refering to the six-acre parcel that the bank seized from Abe Gosman, a businessman who made his money building nursing homes. It was, by Trump’s estimation, the “second greatest house in America,’” conveniently just a ten-minute drive from the number-one home, Mar-a-Lago.

Gosman had purchased the property in 1988 for around $12 million from Leslie Wexner, Epstein’s benefactor; with a strong initial bid at-auction of $37.25 million, it appeared the financier was about to take it back. But bidding soon shot up to $38.6 million and “Trump had made up his mind to get it no matter the price,” a lawyer present at the auction told the Washington Post. Trump’s bid eventually rose to $41.35 million, and he won the house.

That month also marked the last known contact between the two:

Two weeks after the auction, Palm Beach police followed up on a tip that young girls were seen frequently leaving Epstein’s house.

Four years after Trump won the bid, he sold it to Russian businessman Dmitry Rybolovlev for $95 million — a deal that was investigated by the special counsel as part of Robert Mueller’s inquiry into Trump-Russia connections

2004- in 1994, an American named Charlie Ryan had started a Moscow-based bank called United Financial Group. As Westerners clambered for a piece of the newly accessible Russian economy, United Financial grew quickly. Before long, it had one of the biggest stock-trading businesses in all of Russia.

Wanting to get in on this success story, in 2004 Deutsche struck a deal to buy 40 percent of United Financial, and two years later it acquired the remainder for $400 million. All of a sudden, Deutsche had become a leading player in the chaotic country, the top foreign bank for Russian IPOs and mergers, working for formerly state-owned enterprises that had fallen under the control of a new class of oligarchs.

2004, a newly arrived compliance executive started testing Deutsche’s anti-money-laundering systems and was stunned by what he found. Money was pouring into one of the bank’s main U.S. legal entities—Deutsche Bank Trust Company Americas—from banks in Estonia,Lithuania,Cyprus,and most of all, Latvia.

Deutsche hadn’t batted an eye at the flood of transactions. All that business was lucrative for Deutsche, which pocketed fees on each transaction, but it spelled trouble with regulators. “You’ve got a big problem in Eastern Europe,” the new compliance executive warned his boss. “Dude, you have no idea,” came the unsettling reply.

Unlike Deutsche, the Federal Reserve had sophisticated software to track suspicious money flows,and it had been watching the Russian cash going to Latvia and then to the United States, where it soon disappeared into the luxury real estate market.

In 2005, a team of regulators walked from the New York Fed around the corner to Deutsches Wall Street offices, where they laced into executives for their Latvian lapses. The executives braced for a large penalty—something in the $100 million range seemed likely—and were pleasantly surprised when the Fed,along with

New York’s banking regulator, simply issued a written order requiring the bank to improve its anti-money-laundering systems. The caveat was that the next time similar problems cropped up, Deutsche wouldn’t get off so lightly.

2005, Steinmetz teamed up with another diamond magnate, Lev Leviev, to purchase the top ten floors of Israel’s Diamond Tower which also houses the Israeli Diamond Exchange. Haaretz.com reported that “the buyers intend to build a connector from the 10 floors – the top 10 floors of the building – to the diamond exchange itself in order to benefit from the security regime of the other offices within the exchange.” And benefit they did.

According to one website reporting on a Channel 10 (Israel) news story, from 2005 – 2011, an “underground” bank was set up to provide “loans to firms using money taken from other companies while pretending it was legally buying and selling diamonds.” The bank apparently washed over $100 million in illicit funds over the course of six years and both Steinmetz and Leviev were directly implicated as “customers” of the bank but I don’t believe either of them were charged in the case.

Then there’s HSBC’s involvement in the diamond industry and Leviev’s ties not only to arms dealer Arcadi Gaydamak via Africa-Israeli Investments but Roman Abramovich through the Federation of Jewish Communities in Russia (FEOR) but seriously, who’s got the time?

2004- Soros provided seed money for Mnuchin to start his own hedge fund, Dune Capital Management, “named for a spot near his house in the Hamptons,” according to Bloomberg Businessweek. Dune made investments in at least two Trump-related real-estate projects, and ended up settling a lawsuit with Trump over one of them.

At its peak, the firm had roughly $2 billion and was backed by the billionaire investor George Soros. It had a taste for real estate, movie financing deals and exotic investments including life insurance policies, which Dune bought through a third party at discounted prices from cash-poor older Americans.

Dune had plans to package the insurance policies — called life settlements — into bonds that could be sold to investors. Life settlements represent one of the most macabre actuarial bets that Wall Street has dreamed up. It’s a wager that the elderly person selling the policy will die sooner rather than later, meaning the hedge fund does not have to make many premium payments to keep the insurance policy in force and collect the payout upon that person’s death.

But the market for life settlements largely collapsed during the financial crisis.

Eventually, Dune, like many hedge funds during the worst of the crisis, faced investor withdrawals. Mr. Mnuchin and one of his co-founding partners, Chip Seelig, decided to wind down the operation. The real estate arm of Dune was spun off into a firm led by Dune’s third co-founder, Daniel M. Neidich.

2005-, Manafort began a secret deal with Deripaska whereby Manafort’s firm was paid $ 10 million per year to influence politics, business dealings, and media coverage inside the US, Europe, and the former Soviet republics in a way that would benefit Vladimir Putin’s government.

Deripaska was “among the 2–3 oligarchs Putin turns to on a regular basis,” according to a diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks, so Manafort clearly knew whose interests were being served. “We are now of the belief that this model can greatly benefit the Putin Government,” Manafort wrote in the proposal. He added that his firm would “be offering a great service that can re-focus, both internally and externally, the policies of the Putin government.”

2005-A Kremlin-backed think tank, the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation (IDC), was formed in New York in 2008 under Putin adviser Andranik Migranyan, which often partners with CFTNI. Migranyan was selected to run the IDC by Sergey Lavrov, according to a confidential State Department cable released by WikiLeaks.

Goodman suggests the IDC originated when Kremlin adviser Gleb Pavlovsky, Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska and Paul Manafort to discuss forming a Russian-funded think tank, as reported in 2005 by the Russian-American newspaper Kommersant.

According to Forbes magazine, Deripaska is Russia’s sixth-wealthiest man, with an estimated fortune of $13.3 billion. In 2001, about a year after Putin signed a decree granting legal immunity to Yeltsin’s family, Deripaska married Yeltsin’s granddaughter, thereby cementing his own immunity and influence.

In 2010, the Financial Times published a story exploring Deripaska’s business relations with Sergei Popov and Anton Malevsky, alleged heads of Russian organized crime groups.

As early as 2005, Manafort secretly worked for Deripaska on a confidential strategy that he would influence politics, business dealings and news coverage inside the United States, Europe and former Soviet republics to “greatly benefit the Putin Government,”

.Manafort told Deripaska he was pushing policies as part of his work in Ukraine “at the highest levels of the U.S. government — the White House, Capitol Hill and the State Department.”

According to The Nation, Deripaska’s business partner, Nathaniel Rothschild, owns a stake in Diligence LLC, where Burt served as an Executive Chairman.

Diligence is a Washington-based, private global intelligence firm with William Webster, former director of the CIA and FBI on its advisory board.Diligence was co-founded by Nicholas Day, a former officer with M15. The chairman of Diligence’s chairman is Michael Howard, the former head of the British Conservative party.

In 2007, Diligence LLC was charged over allegations of corporate espionage in a case that involved the Alfa Group, for whom Burt functioned as an advisor, working closely with its co-founder, CFR member and the second wealthiest man in Russia, Mikhail Fridman.

Diligence offered Deripaska corporate intelligence gathering, visa lobbying, and help in obtaining a $150 million World Bank/European Bank for Reconstruction and Development loan that was useful in providing cover for Western investors concerned about RUSAl

2005-The thing that none of us knew on that November day in 2005 was that Bill Browder himself was about to run into trouble in Putin’s Russia.

Only days after his presentation in Monaco he was detained at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, had his visa revoked and was escorted onto the first flight back to London, barred indefinitely from entering Russia where he had lived and managed his firm.

In 2005, Browder was very bullish on Russia and said that every investor in the world should own shares of companies like Gazprom. After his exile he was very negative, explicitly warning investors to stay away from Russia

2005- Trump went back to Justin Kennedy’s commercial real estate group, seeking another enormous loan. This one was to build a ninety-two-story skyscraper in Chicago, which Trump planned to name the Trump International Hotel & Tower.

It was going to be one of the tallest buildings in America, a glittering riverfront high-rise that included a hotel, a spa, restaurants, and nearly 500 condominium units. Trump seduced the Deutsche bankers with flights on the same 727 that had recently brought Byrnes team to Florida.

He invited Kennedy to Trump Tower, six blocks away from Henry Villard’s garish Madison Avenue mansion. Trump lavished him and his colleagues with praise and explained that his daughter, Ivanka, would be in charge ofthe proposed Chicago development—that’s how important this project was to the Trump Organization, as his company was called.

Just as Waugh hadn’t warned Byrne about the rejected Trump loan,now Byrne didn’t warn Kennedy’s crew about the bank’s recent bad Trump experience. (“We just looked the other way,” explains an executive in Byrne’s division. “That was the Deutsche Bank culture.”)

Even so ,the Chicago loan had all the hallmarks of troubles.Not only had Trump defaulted over and over again, but before extending another loan, Deutsche conducted an informal audit of Trump’s finances.

He had declared to the bank that he was worth roughly $3 billion. But when Deutsche crunched the numbers that his accountants had compiled, they concluded that the real number was about$788 million.

In otherwords, Trump had been saying his net worth was almost four times larger than it really was. For most banks, this would have been the final straw; how could you trust a guy to repay a huge loan if he was lying about how much money he had?

Deutsche, though, was undeterred. Executives were so eager for growth and big deals, so convinced of their own intelligence, that they managed to look past the obvious red flags. (Plus, Trump hadn’t defaulted on the loans that the commercial real estate group had made dating back to the Mike Offit era.)

In February 2005, Deutsche agreed to lend him $640 million for the Chicago project. The actual recipients were limited liability companies that the Trump Organization had created specifically for this occasion to shield its owner if the project went bust. But Trump also agreed to provide an “unconditional payment guaranty”of$40million—that was what Trump personally would owe if his LLCs defaulted. (Trump also paid Deutsche a $12.5 million fee in connection with the loan.)

Deutsche soldoff pieces of the loan to other banks and investors, but it kept plenty of it on its own books, too. It was a fateful transaction, one that would shape Deutsche’s relationship with Trump for years into the future.

Around this time, and out of public view, Deutsche provided a series of other services to Trump. For starters,it created numerous“special purpose vehicles”to make it easier for him quietly to buy properties internationally.

Thanks to the magic of derivatives, the vehicles—with obscure names that hid their connection to Trump—enabled Trump to do real estate deals in places like Eastern Europe and South America without putting any of his own money on the line; not only was he taking out loans to finance the deals, but he was also using other people’s money to cover the small“equity”portion of the purchases.

For a fee, Deutsche and investors bore the risk, over many years, that the projects would fail. This sort of structure was not unheard-of for major real estate developers. “It’s a well-seasoned financing technique,”explains Mark Ritter,a Deutsche executive who worked on the transactions at the time. But it added to the bank’s already deep exposure to Trump—and helped the mogul strike under- the-radar deals in far-flung locales, including those that were popular destinations for people looking to hide assets.

2006-Deutsche also helped Trump find people to buy condos in his properties. When he partnered in 2006 with a Los Angeles developer to build a Trump-branded resort in Hawaii, Deutsche organized get-togethers in London and elsewhere to connect Trump and his partners with wealthy clients who used anonymous shell companies to buy blocks of units in the sprawling Waikiki hotel complex.

The bank played the same behind-the-scenes matchmaking role when Trump sought to drum up interest in a planned resort in Baja, Mexico. (That project collapsed.)

In both cases, Deutsche steered very rich Russians into the Trump ventures, according to people who were involved in the deals—just a couple of years after American regulators had punished the bank for whisking Russian money into the U.S. financial system via Latvia.

Some members of Jain’s inner circle had discussed the potential pitfalls of the Trump relationship,and they were worried.It wasn’t only the not-insignificant risk that Trump would default on loans. The bankers also knew how filthy the New York real estate industry could be. They talked about Trump’s well- documented ties to the organized crime world,and the possibility that Trump’s real estate projects were Laundromats for illicit funds from countries like Russia, where oligarchs were trying to get money out of the country.“

There was more to Trump’s relationship with Deutsche than money. The bank was still trying to establish its brand in the United States,and despite his financial woes,Trump—whose hit TV show The Apprentice had debuted in 2004 on NBC—provided splashy publicity for the bank.

2006- U.S. Attorney Alex Acosta violated the law in granting Epstein a sweetheart plea deal in 2006 without notifying Epstein's many underage victims.

They numbered scores and perhaps in the vicinity of one hundred, with two claiming at one time in a withdrawn lawsuit that they had been raped by both Epstein and Trump

The two, "Katie" and "Maria," have alleged that Epstein and Trump raped them at ages 12 and 13. But the lawsuits have been withdrawn, purportedly after death threats.

Acosta, now Trump's Labor Secretary in charge of federal efforts to fight sex trafficking nationwide, bagged the federal-state Epstein case when he was a Bush U.S. attorney in Miami, thereby benefiting the wealthy Epstein and his powerful friends, who have included Prince Andrew of the United Kingdom's royal family, Bill Clinton and Alan Dershowitz.

2006-Ackermann put a fellow Swiss German, Pierre de Week, in charge of reinvigorating the Deutsche bank business, and de Week hired small group of executives from Citi. One of them was Tom Bowers.

Bowers would handle Epsteins account which he had brought over from JP morgan after they stopped doing business with Epstein.

He surveyed the New York banking and social scene, asking anyone he could find who the best private banker out there was. A single name kept popping up: Rosemary Vrablic.

Rosemary Vrablic started in banking in the mid 80’s with Israeli Bank Leumi where the Kushners were customers.

Bowers met with Vrablic and was impressed. Her training over the years had left her with a keen grasp of how to structure loans to please clients while minimizing default risks.

In the summer of 2006, Deutsche persuaded the forty-six-year-old Vrablic to defect from Bank of America. Part of the deal was that she would report exclusively to Bowers and that she was guaranteed to be paid about $3million a year for multiple years,an unusual arrangement at the time.

To differentiate itself from a crowded field of competitors, Deutsche planned to do deals that were too risky or too complicated for rival banks to stomach—the same strategy that Mike Offit had deployed a decade earlier when trying to get the commercial real estate business off the ground.

“Deutsche needs damaged clients,” one of Vrablic’s former colleagues would explain. Financially healthy and uncontroversial billionaires could easily go to bigger,more prestigious American banks.Deutsche picked up the scraps,including clients with unusual needs.

When the billionaire Stan Kroenke wanted a loan to buy the iconic British soccer club Arsenal, some large American banks balked. Vrablic,however,hammered out a transaction in which. Deutsche would accept as collateral some of Kroenke’s other professional sports teams in the United States. The deal got done, and Deutsche reaped millions of dollars in advisory fees and interest on the loan—

“Rosemary saved the day again” became a common refrain inside the bank, which counted on her to rake in tens of millions of dollars in annual revenue. She was by far the top producer in the bank’s New York offices. Vrablic, by now bestowed with the uncreative nickname RV, kept mementos from her loans— including a golden shovel,to commemorate a construction project she financed—on display in her office.

Despite, or perhaps partly because of, her prowess, Vrablic wasn’t very popular inside Deutsche. Envious investment bank¬mers perceived her as a threat to their own relationships with cli¬ments. She had a tendency to be brusque, refusing to collaborate withprivate-banking colleagues;on an annual performance review, she was told she needed to improve her teamwork.

She stirred up even more resentment when Deutsche higher-ups trotted her out to regional offices to teach the bank s wealth managers how to boost their lending volumes. (“We felt disrespected,” one sniffed.)

Vrablic’s deal to report directly and exclusively to Bowers, the head of U.S. wealth management, meant that she bypassed the CEO of the private bank, to whom all of her colleagues reported. The arrangement added to her colleagues’ resentment of what looked like special treatment.

2006-Charlie Ryan became Deutsche’s CEO for Russia. “It’s obvious today that Russia is hot,” he explained to a reporter in 2006. “Three years ago”—when Ackermann had stomped on the bank’s gas pedal—“Deutsche Bank was the only one to see it.”

This did not strike everyone as smart. Some executives had reservations about doing business in Russia and, in particular, doing business with United Financial.

Ryan was an enigma; what was a boisterous American doing ensconced in the Moscow business scene? Executives, including one of the bank’s highest- ranking internal lawyers, wondered aloud whether he was an undercover CIA agent. Was this really the kind of person the bank should be tethering its reputation to?

A Harvard graduate, Ryan first came to Russia in the early 1990s as a banker for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) when he landed in St Petersburg to help advise the local authorities on how best to privatise local municipal assets.

One of his key initial contacts in the mayor’s office was one V. Putin, who was deputy mayor at the time to Anatoly Sobchak.

Spotting a gap in the market, Ryan and a partner Boris Fedorov decided to strike out by setting one of the country’s first ever investment banks.

“Charlie has had the intelligence to understand the Russian political and economic context before positioning, and to pick his partners well,” commented Eric Kraus, an independent fund manager in Moscow.

“He is totally without arrogance or strong ideological biases – he does not lecture the Russians on what they should be when they grow up, and as a result, he has been well received by the domestic investment community.”

Mr. Ryan co-founded United Financial Group (UFG) with Fedorov and became its Chairman and CEO in 1994.

Fedorov, Russia’s first modern finance minister under Boris Yeltsin, brought political clout and connections in the Kremlin while Ryan brought a hard-nosed ability to close a deal and rare understanding among foreign financiers on how to do `biznes’ in Russia.

In 1998, Mr. Ryan initiated the New Technology Group within UFG Asset Management, which sponsored an early-stage technology investment in ru-Net Holdings whose investments include Yandex.

In 2004 Ryan sold 40% of the investment bank UFG for $70m to Deutsche Bank. Deutsche bought the remaining 60% from the US banker and his colleagues in 2006 for the mouth-watering sum of $600m in 2006.

The two-step deal gave Deutsche the platform it coveted and within a year it established an unassailable lead in domestic equity and debt capital market league tables.

Ryan stayed on board as country chief of Deutsche Bank in Moscow as the German lender tried to handle the delicate succession issue. Key bankers defected to foreign and domestic rivals as lock-ins expired.

In 2008 Ryan took the helm at UFG Asset Management, a separate entity, and the same year he and Fedorov raised about $65m by selling a 40% stake in the company to Deutsche.

2006-Another concern was that Deutsche was pursuing business with Russian oligarchs, and that meant it was almost certainly getting its hands dirty with corrupt money. The only question was when, where, and how much—and whether the dirt would leave a permanent stain on the bank.

This, though, was what it took to achieve Ackermann’s return on-equity target—especially since Ackermann himself was an unabashed cheerleader of the bank’s expansion into Russia. Just as Georg von Siemens’s entrancement with the United States had led Deutsche into the Henry Villard swamp a century earlier, now Ackermann’s fixation with Russia would spur Deutsche into a similar quagmire.

Like Siemens in America, Ackermann was blinded by his fascination with Russian culture and had developed tastes for its theater, opera, and food (blini with caviar was among his favorite dishes). He visited the country as much as once a month,striking up what he described as friendships with some of the bankers in Vladimir Putin’s inner circle.

One of them, Andrey Kostin,was the chief executive of VTB Bank. VTB was a government-controlled lender that had financed Russian intelligence agencies and was suspected of conducting espionage via its archipelago of international outposts. (Two leaders of the FSB, the Kremlin’s modern-day spy agency, sent their sons to work at VTB.)

None of this seemed to deter Ackermann. He signed off on a $1 billion credit line that Deutsche extended the Russian bank. And at a cocktail party in Saint Petersburg, he suggested to Kostin that VTB should consider building its own investment bank to speed the development of Russia’s capital markets. Kostin heeded the advice.

2006-The Trumps began spending more and more time in Russia. Donald Jr., executive vice president of development and acquisitions for the Trump Organization, made about half a dozen trips to Russia over the course of a year and a half.

“[ I] n terms of high-end product influx into the US, Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets,” he later told a Manhattan real estate conference. “. . . We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia.”

And finally there was Donald Trump, emerging from a decade of litigation, multiple bankruptcies, and $ 4 billion in debt, to rise from the near-dead with the help of Bayrock and its alleged ties to Russian intelligence and the Russian Mafia. “They saved his bacon,” said Kenneth McCallion, a former federal prosecutor who filed suit against Mogilevich, Paul Manafort, Ukrainian oligarch Dmitry Firtash, and others on behalf of former Ukrainian prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko.

But Trump’s rescue by the Russians was not cost-free. By working with Bayrock, McCallion says, Trump may well have been performing gigantic favors for Vladimir Putin without even knowing it.

Indeed, in 2016, Trump’s political adversaries commissioned Christopher Steele, a former MI6 agent, to dig up opposition research on Trump, and among the most astonishing allegations in the infamous thirty-five-page Steele Dossier, which alleges Trump has been severely compromised by Russia, is that Trump unknowingly regularly supplied intelligence to Vladimir Putin.

On the face of it, Steele’s allegation seems absurd to anyone familiar with Trump’s insistent tweeting, impulsive outbursts, and scores of outrageous indiscretions. Who could possibly believe he had the discipline necessary to carry out such a daring intelligence operation?

On the other hand, Steele’s dossier specifically said the intelligence in question was about “the activities of business oligarchs and their families’ activities and assets in the US, with which PUTIN and the Kremlin seemed preoccupied.”

That kind of intel was crucial to Putin, because his relationship with the oligarchs often seesawed back and forth. (US intelligence would also be interested and Sater was a cooperator, why not Trump too? Double agent? )

Putin oversaw them with an iron fist, and when they fell out of favor, they either toed the line or ended up being purged jailed and/ or dying under mysterious circumstances

2006-In addition to being wired into the Kremlin, Sapir’s son-in-law, Rotem Rosen, was a supporter of Chabad along with Sater, Sapir, and others at Bayrock, and, as a result, was part of an extraordinarily powerful channel between Trump and Putin.

(Chabad as intermediate between Putin and Russian and US/Israel oligarchs?)

After all, the ascent of Chabad in Russia had been part of Putin’s plan to replace older Jewish institutions in Russia with corresponding organizations that were loyal to him.

When they began, Russia already had a chief rabbi, Adolf Shayevich, who was recognized as such by the Russian Jewish Congress. But when Abramovich and Leviev installed Chabad rabbi Lazar at the head of their rival organization, the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia, the Kremlin recognized Lazar as Russia’s head rabbi and removed Shayevich from its religious affairs council.

Consequently, the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia, the voice of Chabad in Russia, became so close to Putin that he even made a point of attending the dedication of their center in Moscow’s Marina Roscha neighborhood in 2001.

With Chabad’s Rabbi Berel Lazar leading the way, the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia was now providing Putin with a Jewish “umbrella” that allowed him to battle Vladimir Gusinsky, whose media properties had become critical of him and who even dared to back candidates opposed to Putin. “

But another reason for the close ties between Chabad and Putin was that both Lazar and Leviev had promised Putin that they would make their connections available to the Kremlin and “open doors to the corridors of power in Washington.”

At the time, Trump’s comeback in real estate and his ascent in TV were in full swing, but his political prospects were still dicey at best. However, his role in Bayrock and its real estate deals with Russian oligarchs were real and provided a connection to Moscow. That’s what made the Chabad channel so mysterious.

First and foremost, the biggest contributor to Chabad in the world was Leviev, the billionaire “King of Diamonds” who had a direct line to Rabbi Berel Lazar, aka “Putin’s rabbi,” to Donald Trump, and to Putin himself dating back to the Russian leader’s early days in St. Petersburg.

Leviev would later make major real estate transactions with Jared Kushner, including selling the retail space in the former New York Times Building to Kushner for $ 295 million.(Kushner borrowed most of the money from Deutsche Bank which was known to deal with Russian money launderers).

Levievs company (prevezon holdings) was involved in a government-prosecuted money laundering based on Browders say so . He avoided trial in 2017 with a financial settlement for a paltry 6 million — a year after Kushner and other members of Trump’s campaign team met with the company’s legal counsel in New York)

As an undergraduate at Harvard, Jared had been active at the campus Chabad House at Harvard. Jared later married Ivanka Trump and became a senior adviser to her father in the White House. Jared and Ivanka were also close to Chabad donor Roman Abramovich and his wife, Dasha Zhukova.

Another major contributor was Jared’s father, charles Kushner, an American real estate developer who was eventually jailed for illegal campaign contributions, tax evasion, and witness tampering.

Indeed, one of the biggest contributors to Chabad of Port Washington, Long Island, was Bayrock founder Tevfik Arif, a Kazakh-born Turk with a Muslim name who was not Jewish, but nonetheless won entry into its Chai Circle as a top donor.

The Port Washington founder and head rabbi, Shalom Paltiel, happened to be an acolyte of Rabbi Berel Lazar, Paltiel’s “dear friend and mentor,” as he referred to Lazar. But he was also close to Felix Sater and later named Sater “man of the year” for Chabad of Port Washington.

In addition to Sater, Daniel Ridloff, a fellow Bayrock employee, was a member of the Port Washington Chabad house. Chabad supporters Rotem Rosen and his bride, Zina Sapir, of course, were tied to Bayrock through Zina’s father, Tamir Sapir, and they were such close personal friends of Trump that he let them have their 2007 wedding at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago, with Lionel Richie and the Pussycat Dolls performing.

2006 On April 28, Josef Ackermann, chairman of the management board and the Group Executive Committee of Deutsche Bank, signed a “cooperation agreement” with Vladimir Dmitriev Chairman of Vneshekonombank (VEB) — a government-owned Russian development bank.

The stated objective of this agreement was to further intensify the cooperation between the two institutions on selected projects under the Public Private Partnership (PPP) and Private Finance Initiative (PFI) structures in the Russian Federation. This “cooperation agreement” becomes more pertinent when we consider Jared Kushner’s relationship with Deutsche.

2006-In the year he was murdered, Litvinenko was investigating suspicions that Roman Abramovich was involved in money-laundering and illegal land purchases.

The Jerusalem Post recently ranked Abramovich as the tenth wealthiest Jew in the world. Abramovich is the primary owner of the private investment company, Millhouse LLC and is best known outside Russia as the owner of Chelsea Football Club, a Premier League football club. In 1996, he acquired the oil company Sibneft, for about $US100 million, and sold it to Gazprom for $US13 billion a decade later.

His $5.6-billion legal dispute with a former business partner, Boris Berezovsky, nicknamed the “Godfather of the Kremlin,” uncovered evidence involving illicit activity including protection rackets, contract killings, arms dealings.

2007, Trump hosted the wedding of Sapir’s daughter, Zina, at Mar-a-Lago. The event featured performances by Lionel Ritchie and the Pussycat Dolls. The groom, Rotem Rosen, was Leviev’s “right-hand man” and the CEO of the American branch of Africa Israel, Leviev’s holding company.

Five months later, in early June of 2008, Zina and Rotem held a bris, a Jewish religious male circumcision ceremony, for their newborn son, which Leviev personally arranged to take place at Schneerson’s grave in Queens. Trump attended the bris.

A month earlier, in May of 2008, Trump and Leviev had met to discuss possible real estate projects in Moscow, according to a Russian news report.

Leviev had become the single largest funder of Chabad worldwide. Sapir, an active Chabad donor as well, joined Leviev in Berlin to tour Chabad institutions in the city in 2008.

2007-Exactly how much Trump knew about Sater and the inner workings of Bayrock was unclear—which is exactly the way he seemed to want it. But on December 19, 2007, Trump gave a deposition in a lawsuit he filed against author Timothy O’Brien. Two days earlier, New York Times reporter Charles Bagli had revealed that Felix Sater had a hidden past, and now that Trump was under oath it was possible to determine the extent of his knowledge. When asked about Sater’s criminal history, Trump testified, “[ I’m] looking into it because I wasn’t happy with the story. So I’m looking into it.”

In other words, under oath, Trump had admitted that he knew about Sater’s run-ins with the law. Because the deposition was marked “Confidential” and kept under seal, Trump may not have expected it to become public.

Regardless, Trump’s knowledge of Sater’s past was now a matter of court record. According to Jonathan Winer, the former money-laundering czar in the Clinton administration, if someone in Trump’s situation failed to investigate such allegations he would be “open to charges of ‘willful blindness’ in terms of the knowledge he had.”

“The responsible course of action would have been to have Sater resign and disclose Sater’s past to interested parties,” says Richard Lerner, who, with Frederick Oberlander, filed a qui tam lawsuit against Bayrock in 2015—that is, a civil suit that rewards private entities working to recover funds for the government. In this case, they charged Bayrock with laundering $ 250 million in profits from Trump SoHo and other projects, and setting up elaborate mechanisms to evade more than $ 100 million in state and federal taxes.

Sater’s attorney, Robert Wolf, characterized the allegations of “their extortionate litigations” as “baseless and highly defamatory.” But rather than extricate himself from the deal with Bayrock and a partnership with a convicted felon, Trump kept silent about Felix, continued working with Bayrock, and ultimately profited from the arrangement.

Indeed, according to Bayrock’s internal emails, rather than disclose the truth, Trump even saw the predicament as an occasion to renegotiate his fees—upward, of course. “Donald . . . saw an opportunity to try and get development fees for himself,” Sater emailed investors a few days after the deposition.

2007-On the 4th June 2007, while Browder travelled to Paris for a meeting with Hermitage Global’s directors, Artem Kuznetsov brought 25 plainclothes police to raid Browder’s offices in Moscow. At the same time, another police squadron raided the offices of the law firm Firestone Duncan with whom Browder had done a lot of business over the years.

Apparently, the police were after the files for “Kameya,” a Russian company owned by one of their clients through which Browder advised them on investing in Russia.

Browder’s lawyer in Moscow, the American Jamison Firestone. He came to Moscow in 1991 aged only 25. Landing in the chaos of the Russian transition, he founded a law firm together with another young American, and until Kuznetsov’s raids pretty much did well for himself.

Browder tells us that he liked Jamie Firestone and makes subtle contrast between this fit, handsome, “straight-talking,” honest American and the ghoulish Russians whom he describes as having “great skill in talking without saying anything.”

The official reason for the police raids: the tax crimes department of the Moscow Interior Ministry had opened a criminal case against Ivan Cherkasov, Hermitage’s Chief Operating Officer. They accused him of underpaying $44 million in taxes related to a Russian company named Kameya, which Hermitage Capital controlled and through which it transacted its investments.

Sergey Magnitsky’s assignment was to review all of Kameya’s tax returns. He quickly established that Browder’s COO Cherkasov had done nothing wrong, and should be in the clear legally

Department K proceeded methodically to raid Browder’s bankers in Moscow: Credit Suisse, HSBC, Citibank and ING, apparently looking for Hermitage assets.

Browder had by this time raised at least $625 million for his new hedge fund, Hermitage Global, and his prospects in London were again looking very promising. His family, his team, as well as his clients’ money were all safely out of Russia, and his lawyers assured him that it would be impossible for the Russian state to seize his personal assets.

Browder proceeds to deconstruct the scheme that the bad guys used in their criminal acquisition of money using the firms they stole from him. Hermitage earned $973 million in profits for 2006, through its three Russian subsidiaries: Rilend, Parfenion, and Makhaon. Their combined tax bill for the year was $230 million, and Browder claims they paid them in full.

But as the bad guys took control of Hermitage’s three subsidiaries, they arranged, with the help of phony courts and impostor prosecutors, judges and defence attorneys, to obtain legal judgments against the firms in the exact amount of their profits for 2006: $973 million.

The effect of these judgments was to retroactively zero out Hermitage’s firms’ profits. This way the bad guys could now apply for a full refund of taxes Browder’s firms previously paid. The refunds were soon approved and settled, and the tax authorities paid out $230 million to the bad guys into two obscure Moscow banks from where they quickly disappeared offshore.

As Browder will inform us later, this was “the single largest tax refund in Russian history.”

2007-Two hedge funds run by the investment bank Bear Stearns had just collapsed in July, 2007-early tremors in what would become a global financial earthquake.

One hot night, Deutsche banks Anshu and a few colleagues attended a dinner with a group of leading hedgefund managers and private equity executives. “The talk was all about how to avoid the oncoming train,” a Deutsche executive would recount.

Jain knew things were bad, but the apocalyptic tone rattled him. Around 9:30 P.M., he summoned his top lieutenants to a windowless hotel conference room and issued an order: “Put the ship into complete reverse.”

The bank needed to accelerate the sales of its riskiest positions, especially anything tied to the U.S. housing market, and they needed to do it now. It was a bold, prescient move, one that arguably saved the bank, and it would prove to be Jain’s finest hour.

The problem was that it was easier to order a fire sale than to actually ignite one. Much of the worst stuff sitting on Deutsche’s books wasn’t easily salable—not many people wanted to buy risky securities right then. And Deutsche’s computer systems were so disjointed that it was hard to even figure out what the bank owned.

Dark smoke billowed out of the abandoned Bankers Trust headquarters in downtown Manhattan.

It was a Saturday afternoon in August 2007, and the dark tower, cloaked in black mesh ever since 9/11, had caught fire after a construction worker dropped a lit cigarette. Hundreds of firefighters rushed to the scene, desperate to prevent the blaze from spreading and the poisons inside the structure from contaminating the surrounding area.

The conflagration soon engulfed thirteen floors of the building. It took seven hours to extinguish.Two firemen perished.

A bad omen signaling what was in store for the economy

2008- As the financial crisis reached full throttle in the fall , Donald Trump owed $334 million on Deutsche’s 2005 loan for his Chicago skyscraper.

The Trump loan had been diced into mortgage-backed bonds that Deutsche had sold to investors, while also keeping a portion for itself. The loan had been due in May 2008, but Deutsche, acting on behalf of itself and the bondholders, agreed to grant Trump a 6 -month extension.

With the November due date approaching, Trump sought another extension.This time the bank said no.

Trump,however,had no intention of repaying the loan on time. He asked his lawyers to figure out a work-around. One of them dissected each of the loan documents and,on a conference call with his colleagues to brainstorm how their client could wriggle out of his obligations, mentioned the existence of a so- called force majeure—act of God—provision in the loan agreement. That meant that in the event of an unanticipatable catastrophe, like a natural disaster, the contract wasn’t enforceable.

A lawyer on the call piped up that Alan Greenspan had just called the financial crisis a “credit tsunami”—and what was a tsunami if not a natural disaster, an act of God?

One lawyer, Steve Schlesinger,presented the idea to Trump.“It’s brilliant!” he declared, and Schlesinger and his colleagues basked in the warmth of Trump’s pleasure. He instructed his lawyers to execute the plan.

Three days before the loan was due, the lawyers wrote to Deutsche that Trump considered the financial crisis to represent a force majeure that allowed him to stop paying back his loan.

Days later, Trump filed a lawsuit citing the provision and accusing Deutsche of engaging in “predatory lending practices”— toward him!—and of helping ignite the financial crisis.

“Deutsche Bank is one of the banks primarily responsible for the economic dysfunction we are currently facing,” Trump asserted. In an extraordinary act of chutzpah, he sought damages of $3 billion.

Deutsche filed its own suit, seeking the $40 million Trump had personally guaranteed back in 2005. The bank pointed out that the same day Trump had notified Deutsche that the financial crisis constituted a contract-voiding act of godly devastation, he was quoted in two newspapers boasting about how he was unscathed by that very crisis.

One of his deputies was quoted bragging that Trump’s company had nearly $2 billion, ready to be deployed on a moment’s notice.

In trying to get Trump to pay back the money he owed, the bank made a persuasive argument for why it should never have loaned him that money in the first place. Deutsche’s lawsuit quoted from Trump’s book, Think Big and Kick Ass in Business and Life, in which the future president explained how he had handled banks during a real estate downturn in the 1990s. “I turned it back on the banks and let them accept some of the blame,”

Deutsche argued in the suit: “The fact that he is now resorting to the same tactics he has consistently employed throughout his career as a real estate magnate should surprise no one.” Indeed.

Shortly after the suit was filed, Trump bumped into Justin Kennedy. “Nothing personal,” Trump said. Kennedy replied that there were no hard feelings: Business was business. But when senior Deutsche executives learned about Trump’s litigation, they were irate.“

Kennedy, having made a killing off the financial crisis with CDO’s that cashed in on the crisis and now seeing an important client fall by the wayside, decided to leave the bank at the end of 2009.

Ultimately the parties settled in 2010 and Trump was given 2 years to pay up 40 million

2008, Kostin hired a team of more than a hundred bankers from Deutsche to work for VTB. The defections, while irritating Ackermann and Charlie Ryan, cemented Deutsches bonds to VTB—and to Putin’s clique.

Further gluing the two banks together was the fact that Deutsche in 2000 had hired Kostin’s son, Andrey Jr., in the bank’s London office, straight out of university. He would spend most of the next decade with Deutsche, eventually becoming a senior investment banker. Kostin Jr.’s prominent role, Ackermann would explain to a Russian newspaper years later, “is testimony to our good relationship”with the Russian financial establishment.

That good relationship extended to helping wealthy Russians launder money into the United States—a crucial service,since few American banks were willing to accept the legal risks associated with moving suspect funds into the country.

Oligarchs would move money to banks in neighboring Latvia. Those Latvian banks had “correspondent” relationships with Deutsche that allowed them to transfer money directly into American accounts set up in the names of innocuous-sounding shell companies.

2008-In the end, Sater remained managing director of Bayrock through 2008. Trump also continued to participate in the venture and enjoy its profits. “Inducing a bank to lend money based on a fraudulent loan application—i.e., concealing Sater’s criminal past—is bank fraud,” said Fred Oberlander.

“If you know that the loans were procured by fraud yet stay involved, it’s a conspiracy to violate money laundering and racketeering statutes.” “It’s certainly a question for [special counsel Robert] Mueller to look into,” said Jonathan Winer.

“What anyone in Trump’s position should have done is investigate those allegations [about Sater’s criminal past] to ensure that there was not a money-laundering operation.” But Trump wasn’t charged with any crime at the time.

Nevertheless, once condos in the building were finally put up for sale, the project suffered more than its share of problems. The building’s no-man’s-land neighborhood—not really SoHo—with its grand entrance beside Varick Street and the chaotic approach to the Holland Tunnel, made it a difficult sell.

In addition, in order to circumvent restrictive zoning laws, the project was explicitly marketed to prospective buyers overseas as a second or third home, with the highly challenging proviso that owners could live in their apartments only 120 days a year, and never for more than 29 consecutive days in any 36-day period.