The Battle For CHIPS

CHIPS*

Great book here

https://www.amazon.com/Chip-War-Worlds-Critical-Technology/dp/1982172002

Good thread on an event attended by TSMC Morris Chang and the author in Taiwan

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1636185525316124672.html

I suggest you read the above after reading this post or Millers book

Comparable books are Yasha Levines “Silicon Valley” and Annie Jacobsons “The Pentagons Brain” both of which show the huge role of the Military and DARPA on US Tech Development using your money (you would think Tech would give us a discount).

I will present a timeline here mostly from the book, but you really need to read the book in its entirety. Its very well written so its an easy read unlike some non-fiction.

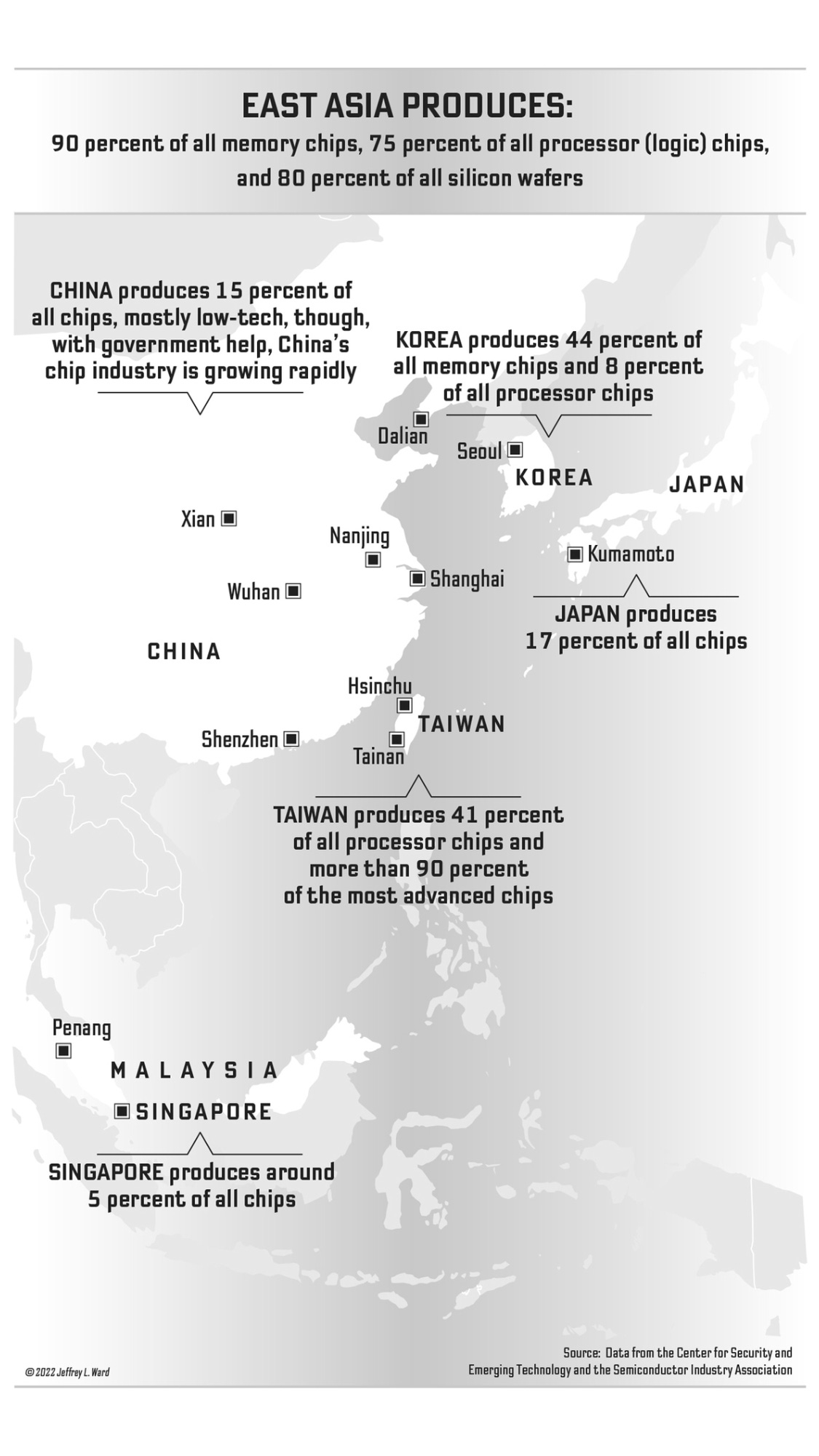

My take home from the book is that the world is dependent on the US for advanced chips even if not made on our soil. Of course, as such there is interdependence. That said, China seems hopelessly behind with little chance of taking over. Even if they somehow grabbed TSMC they would find TSMC would be helpless cut off from the US. China does play a key role providing raw materials and assembling product using these chips.

I learned a bit of history I probably should have known, despite growing up with transistor radios, my TI-57 calculator, Walkmans and the early modem connected PC’s running DOS., and later of course lap tops and now Smart Phones. Heck, even refrigerators use chips today, and soon humans will all be chipped (maybe many of us already we already are).

Note a few sections from the timeline are from wikipedia, which I note, everything else is from book (minor edits for readability)

Timeline

1947-point-contact transistor invented in by physicists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, working under William Shockley at Bell Labs; the three shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for their achievement.

[Wikipedia]

1954-The first production-model pocket transistor radio was the Regency TR-1, released in October 1954. Produced as a joint venture between the Regency Division of Industrial Development Engineering Associates, I.D.E.A. and Texas Instruments of Dallas, Texas, the TR-1 was manufactured in Indianapolis, Indiana. It was a near pocket-sized radio with four transistors and one germanium diode.

[Wikipedia]

1955-, William Shockley founded Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, to develop a new type of "4-layer diode" that would work faster and have more uses than then-current transistors. At first he attempted to hire some of his former colleagues from Bell Labs, but none were willing to move to the West Coast or work with Shockley again at that time. Shockley then founded the core of the new company with what he considered the best and brightest graduates coming out of American engineering schools.

[taken from wikipedia]

1957-Lathrop called the process photolithography—printing with light. He produced transistors much smaller than had previously been possible, measuring only a tenth of an inch in diameter, with features as small as 0.0005 inches in height. Photolithography made it possible to imagine mass-producing tiny transistors. Lathrop applied for a patent on the technique in 1957. With the Army band playing, the military gave him a medal for his work and a $25,000 cash bonus, which he used to buy his family a Nash Rambler station wagon.

1957-Sony TR-63, released in 1957, was the first mass-produced transistor radio, leading to the widespread adoption of transistor radios. Seven million TR-63s were sold worldwide by the mid-1960s. Sony's success with transistor radios led to transistors replacing vacuum tubes as the dominant electronic technology in the late 1950

[Wikipedia]

1957-A core group of Shockley employees, later known as the traitorous eight, became unhappy with his Shockleys management of the company. The eight men were Julius Blank, Victor Grinich, Jean Hoerni, Eugene Kleiner, Jay Last, Gordon Moore, Robert Noyce, and Sheldon Roberts. Looking for funding on their own project, they turned to Sherman Fairchild's Fairchild Camera and Instrument, an Eastern U.S. company with considerable military contracts.

The Fairchild Semiconductor division was started with plans to make silicon transistors at a time when germanium was still the most common material for semiconductor use.

According to Sherman Fairchild, Noyce's impassioned presentation of his vision was the reason Sherman Fairchild had agreed to create the semiconductor division for the traitorous eight.

[also from wikipedia]

Noyce realized his MIT classmate Jay Lathrop, with whom he’d hiked New Hampshire’s mountains while in graduate school, had discovered a technique that could transform transistor manufacturing. Noyce acted swiftly to hire Lathrop’s lab partner, chemist James Nall, to develop photolithography at Fairchild. “Unless we could make it work,” Noyce reasoned, “we did not have a company.”

1958-Jack Kilby, a newly employed engineer at Texas Instruments (TI), did not yet have the right to a summer vacation. He spent the summer working on the problem in circuit design that was commonly called the "tyranny of numbers", and he finally came to the conclusion that the manufacturing of circuit components en masse in a single piece of semiconductormaterial could provide a solution. On September 12, he presented his findings to company's management, which included Mark Shepherd. He showed them a piece of germanium with an oscilloscope attached, pressed a switch, and the oscilloscope showed a continuous sine wave, proving that his integrated circuit worked, and thus that he had solved the problem. U.S. Patent 3,138,743 for "Miniaturized Electronic Circuits", the first integrated circuit, was filed on February 6, 1959. Along with Robert Noyce (who independently made a similar circuit a few months later), Kilby is generally credited as co-inventor of the integrated circuit.

[From wikipedia]

1959-MIT’s Instrumentation Lab had received its first integrated circuit, produced by Texas Instruments, just a year after Jack Kilby had invented it, buying sixty-four of these chips for a price of $1,000 to test them as part of a U.S. Navy missile program. The MIT team ended up not using chips in that missile but found the idea of integrated circuits intriguing.

1959, the Electronics Industries Association appealed to the U.S. government for help lest Japanese imports undermine “national security”—and their own bottom line. But letting Japan build an electronics industry was part of U.S. Cold War strategy, so, during the 1960s, Washington never put much pressure on Tokyo over the issue.

When Texas Instruments sought to become the first foreign chipmaker to open a plant in Japan, the company faced a thicket of regulatory barriers. Sony’s Morita, who happened to be a friend of Haggerty, offered to help in exchange for a share of the profits. He told TI executives to visit Tokyo incognito, register at their hotel under false names, and never leave their hotel room. Morita visited the hotel clandestinely and proposed a joint venture: TI would produce chips in Japan, and Sony would manage the bureaucrats. “We will cover for you,” he told the Texas Instruments executives.

1962-Fairchild was a brand-new company, run by a group of thirty-year-old engineers with no track record, but their chips were reliable and arrived on time. By November 1962, Charles Stark Draper, the famed engineer who ran the MIT lab, had decided to bet on Fairchild chips for the Apollo program, calculating that a computer using Noyce’s integrated circuits would be one-third smaller and lighter than a computer based on discrete transistors. It would use less electricity, too.

Chip sales to the Apollo program transformed Fairchild from a small startup into a firm with one thousand employees. Sales ballooned from $500,000 in 1958 to $21 million two years later. As Noyce ramped up production for NASA, he slashed prices for other customers. An integrated circuit that sold for $120 in December 1961 was discounted to $15 by next October.

Fairchild continued to make its silicon wafers in California but began shipping semiconductors to Hong Kong for final assembly. In 1963, its first year of operation, the Hong Kong facility assembled 120 million devices. Production quality was excellent, because low labor costs meant Fairchild could hire trained engineers to run assembly lines, which would have been prohibitively expensive in California. Fairchild was the first semiconductor firm to offshore assembly in Asia, but Texas Instruments, Motorola, and others quickly followed. Within a decade, almost all U.S. chipmakers had foreign assembly facilities. Sporck began looking beyond Hong Kong. The city’s 25-cent hourly wages were only a tenth of American wages but were among the highest in Asia. In the mid-1960s, Taiwanese workers made 19 cents an hour, Malaysians 15 cents, Singaporeans 11 cents, and South Koreans only a dime.

1964, Texas Instruments had supplied one hundred thousand integrated circuits to the Minuteman program. By 1965, 20 percent of all integrated circuits sold that year went to the Minuteman program.

1964, Japan had overtaken the U.S. in production of discrete transistors, while American firms produced the most advanced chips. U.S. firms built the best computers, while electronics manufacturers like Sony and Sharp produced consumer goods that drove semiconductor consumption.

1965-Bob Noyce claimed that military and space applications used “over 95% of the circuits produced that year.

The first integrated circuit produced for commercial markets, used in a Zenith hearing aid, had initially been designed for a NASA satellite.

it was Fairchild’s R&D team that, under Gordon Moore’s direction, not only devised new technology but opened new civilian markets as well. In 1965, Moore was asked by Electronics magazine to write a short article on the future of integrated circuits. He predicted that every year for at least the next decade, Fairchild would double the number of components that could fit on a silicon chip.

If so, by 1975, integrated circuits would have sixty-five thousand tiny transistors carved into them, creating not only more computing power but also lower prices per transistor. As costs fell, the number of users would grow. This forecast of exponential growth in computing power soon came to be known as Moore’s Law. It was the greatest technological prediction of the century.

1967-Pat Haggerty, the TI Chairman, had asked Jack Kilby to build a handheld, semiconductor-powered calculator. The However, TI’s marketing department didn’t think there’d be a market for a cheap, handheld calculator, so the project stagnated. Japan’s Sharp Electronics disagreed, putting California-produced chips in a calculator that was far simpler and cheaper than anyone had thought possible. Sharp’s success guaranteed most calculators produced in the 1970s were Japanese made.

1968-Taiwanese officials like K. T. Li, who’d studied nuclear physics at Cambridge and ran a steel mill before steering Taiwan’s economic development through the postwar decades, began crystallizing a strategy to integrate economically with the United States. Semiconductors were at the center of this plan. Li knew there were plenty of Taiwanese-American semiconductor engineers willing to help. In Dallas, Morris Chang urged his colleagues at TI to set up a facility in Taiwan.

Many people would later describe the mainland-born Chang as “returning” to Taiwan, but 1968 was the first time he stepped foot on the island, having lived in the U.S. since fleeing the Communist takeover of China.

In July 1968, having smoothed over relations with the Taiwanese government, TI’s board of directors approved construction of the new facility in Taiwan. By August 1969, this plant was assembling its first devices. By 1980, it had shipped its billionth unit.

1968- At Fairchild, Noyce and Moore were unhappy about their lack of stock options and sick of meddling from the company’s head office in New York. Their dream wasn’t to tear down the established order, but to remake it. Noyce and Moore abandoned Fairchild as quickly as they’d left Shockley’s startup a decade earlier, and founded Intel, which stood for Integrated Electronics.

1969-Advanced Micro Devices was formally incorporated by Jerry Sanders, along with seven of his colleagues from Fairchild Semiconductor, on May 1

[Wikipedia]

1972-On May 13, U.S. aircraft dropped twenty-four of the bombs on the Thanh Hoa Bridge, which until that day had been still standing amid hundreds of craters, like a monument to the inaccuracy of mid-century bombing tactics. This time, American bombs scored direct hits. Dozens of other bridges, rail junctions, and other strategic points were hit with new precision bombs. A simple laser sensor and a couple of transistors had turned a weapon with a zero-for-638 hit ratio into a tool of precision destruction. The arrival of TI’s Paveway laser-guided bombs coincided with America’s defeat in the war.

1970-Intel launched its first product, a chip called a dynamic random access memory, or DRAM. Before the 1970s, computers generally “remembered” data using not silicon chips but a device called a magnetic core, a matrix of tiny metal rings strung together by a grid of wires. When a ring was magnetized, it stored a 1 for the computer; a non-magnetized ring was a 0.

The chip would be called a dynamic (due to the repeated charging) random access memory, or DRAM. These chips form the core of computer memory up to the present day. A DRAM chip worked like the old magnetic core memories, storing 1s and 0s with the help of electric currents. But rather than relying on wires and rings, DRAM circuits were carved into silicon. They didn’t need to be weaved by hand, so they malfunctioned less often and could be made far smaller.

Intel planned to dominate the business of DRAM chips. Memory chips don’t need to be specialized, so chips with the same design can be used in many different types of devices. This makes it possible to produce them in large volumes.

1971-Intel, launched a chip called the 4004 and described it as the world’s first microprocessor—“a micro-programmable computer on a chip,” as the company’s advertising campaign put it. It could be used in many different types of devices and set off a revolution in computing.

1973- Marshall had been hired in 1973 to establish the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment and was tasked with forecasting the future of war. Marshall’s grim conclusion was that after a decade of pointless fighting in Southeast Asia, the U.S. had lost its military advantage.

Working with Jimmy Carter’s secretary of defense, Harold Brown, Perry and Marshall pushed the Pentagon to invest heavily in new technologies: a new generation of guided missiles that used integrated circuits, not vacuum tubes; a constellation of satellites that could beam location coordinates to any point on earth; and—most important—a new program to jump-start the next generation of chips, to ensure that the U.S. kept its technological edge.

Led by Perry, the Pentagon poured money into new weapons systems that capitalized on America’s advantage in microelectronics. Precision weapons programs like the Paveway were promoted, as were guided munitions of all types, from cruise missiles to artillery shells. Sensors and communications also began to leap forward with the application of miniaturized computing power.

Perry commissioned a special program, run via the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), to see what would happen if all these new sensors, guided weapons, and communications devices were integrated. Called “Assault Breaker,” it envisioned an aerial radar that could identify enemy targets and provide location information to a ground-based processing center, which would fuse the radar details with information from other sensors. Ground-based missiles would communicate with the aerial radar guiding them toward the target. On final descent, the missiles would release submunitions that would individually home in on their targets.

1978-1979. Despite entering the DRAM market just as Japanese competition was peaking, Micron survived and eventually thrived. Most other American DRAM producers were forced out of the market in the late 1980s. TI kept manufacturing DRAM chips but struggled to make any money, and eventually sold its operations to Micron. Simplot’s first $1 million investment eventually ballooned into a billion-dollar stake. Micron learned to compete with Japanese rivals like Toshiba and Fujitsu when it came to the storage capacity of each generation of DRAM chip and to outcompete them on cost.

[In 1967, Simplot and McDonald's founder Ray Kroc agreed by handshake that the Simplot Company would provide frozen french fries to the restaurant chain.

By 1972, all fries were frozen. The frozen fry deal led to expansion of Simplot potato processing plants and construction in 1977 of a new plant at Hermiston, Oregon. By 2005, Simplot supplied more than half of all french fries for the fast food chain

From wikipedia]

[No wonder we call them chips]

1979, Sony introduced the Walkman, a portable music player that revolutionized the music industry, incorporating five of the company’s cutting-edge integrated circuits in each device. Now teenagers the world over could carry their favorite music in their pockets, powered by integrated circuits that had been pioneered in Silicon Valley but developed in Japan.

1978–79, when approximately 20,000 transistors could be fabricated in a single chip, Carver Mead and Lynn Conway wrote the textbook Introduction to VLSI Systems. It was published in 1979 and became a bestseller, since it was the first VLSI (Very Large Scale Integration) design textbook usable by non-physicists.

[from wikipedia]

Conway and Mead eventually drew up a set of mathematical “design rules,” paving the way for computer programs to automate chip design. With Conway and Mead’s method, designers didn’t have to sketch out the location of each transistor but could draw from a library of “interchangeable parts” that their technique made possible.

No one was more interested in what soon became known as the “Mead-Conway Revolution” than the Pentagon. DARPA financed a program to let university researchers send chip designs to be produced at cutting-edge fabs. Despite its reputation for funding futuristic weapons systems, when it came to semiconductors DARPA focused as much on building educational infrastructure so that America had an ample supply of chip designers. DARPA also helped universities acquire advanced computers and convened workshops with industry officials and academics to discuss research problems over fine wine.

The chip industry also funded university research on chip design techniques, establishing the Semiconductor Research Corporation to distribute research grants to universities like Carnegie Mellon and the University of California, Berkeley.

1980, Intel had won a small contract with IBM, America’s computer giant, to build chips for a new product called a personal computer. IBM contracted with a young programmer named Bill Gates to write software for the computer’s operating system. On August 12, 1981, with the ornate wallpaper and thick drapes of the Waldorf Astoria’s grand ballroom in the background, IBM announced the launch of its personal computer, priced at $1,565 for a bulky computer, a big-box monitor, a keyboard, a printer, and two diskette drives. It had a small Intel chip inside.

1980s, consumer electronics had become a Japanese specialty, with Sony leading the way in launching new consumer goods, grabbing market share from American rivals. At first Japanese firms succeeded by replicating U.S. rivals’ products, manufacturing them at higher quality and lower price. Some Japanese played up the idea that they excelled at implementation, whereas America was better at innovation.

Sporck saw Silicon Valley’s internal battles as fair fights, but thought Japan’s DRAM firms benefitted from intellectual property theft, protected markets, government subsidies, and cheap capital.

Japan’s government subsidized its chipmakers, too. Unlike in the U.S., where antitrust law discouraged chip firms from collaborating, the Japanese government pushed companies to work together, launching a research consortium called the VLSI Program in 1976 with the government funding around half the budget. America’s

The U.S. government was itself deeply involved in supporting semiconductors, though Washington’s funding took the form of grants from DARPA, the Pentagon unit that invests in speculative technologies and has played a crucial role in funding chipmaking innovation.

Sanders, Noyce, and Sporck joined other CEOs to create the Semiconductor Industry Association to lobby Washington to support the industry. When Jerry Sanders described chips as “crude oil,” the Pentagon knew exactly what he meant. In fact, chips were even more strategic than petroleum. Pentagon officials knew just how important semiconductors were to American military primacy.

1981-Fujio Masuoka developed a new type of memory chip in 1981 that, unlike DRAM, could continue “remembering” data even after it was powered off. Toshiba ignored this discovery, so it was Intel that brought this new type of memory chip, commonly called “flash” or NAND, to market. The biggest error that Japan’s chip firms made, however, was to miss the rise of PCs. None of the Japanese chip giants could replicate Intel’s pivot to microprocessors or its mastery of the PC ecosystem. Only one Japanese firm, NEC, really tried, but it never won more than a tiny share of the microprocessor market. For Andy Grove and Intel, making money on microprocessors was a matter of life or death. Japan’s DRAM firms, with massive market share and few financial constraints, ignored the microprocessor market until it was too late.

As a result, the PC revolution mostly benefitted American chip firms.

1982-Intel and AMD entered into a 10-year technology exchange agreement, first signed in October 1981 and formally executed in February 1982. The terms of the agreement were that each company could acquire the right to become a second-source manufacturer of semiconductor products developed by the other; that is, each party could "earn" the right to manufacture and sell a product developed by the other, if agreed to, by exchanging the manufacturing rights to a product of equivalent technical complexity. The technical information and licenses needed to make and sell a part would be exchanged for a royalty to the developing company. The 1982 agreement also extended the 1976 AMD–Intel cross-licensing agreement through 1995. The agreement included the right to invoke arbitration of disagreements, and after five years the right of either party to end the agreement with one year's notice. The main result of the 1982 agreement was that AMD became a second-source manufacturer of Intel's x86 microprocessors and related chips, and Intel provided AMD with database tapes for its 8086, 80186, and 80286 chips.

[Wikipedia]

1984, Philips, the Dutch electronics firm, had spun out its internal lithography division, creating ASML. Coinciding with the collapse in chip prices that sank GCA’s business, the spinoff was horribly timed. What’s more, Veldhoven, a town not far from the Dutch border with Belgium, seemed an unlikely place for a world-class company in the semiconductor industry. Europe was a sizeable producer of chips, but it was very clearly behind Silicon Valley and Japan.

ASML’s history of being spun out of Philips helped in a surprising way, too, facilitating a deep relationship with Taiwan’s TSMC. Philips would be a cornerstone investor in TSMC, transferring its manufacturing process technology and intellectual property to the young foundry. This gave ASML a built-in market, because TSMC’s fabs were designed around Philips’s manufacturing processes

1984- Gordon Campbell and Dado Banatao founded Chips and Technologies, which is generally considered the first fabless firm. One friend alleged it “wasn’t a real semiconductor company,” since it didn’t build its own chips. However, the graphics chips they designed for PCs proved popular, competing with products built by some of the industry’s biggest players. Eventually Chips and Technologies faded and was purchased by Intel.

1985-While pursuing his master’s degree at MIT, Jacobs studied antennas and electromagnetic theory and decided to focus his research on information theory—the study of how information can be stored and communicated.

Standing up from the back row, he held aloft a small chip and declared: “This is the future.” Chips, Jacobs realized, were improving so rapidly that they’d soon be able to encode orders of magnitude more data in the same spectrum space. Because the number of transistors on a square inch of silicon was increasing exponentially, the amount of data that could be sent through a given slice of the radio spectrum was about to take off, too.

Jacobs, Viterbi, and several colleagues set up a wireless communications business called Qualcomm—quality communications—betting that ever-more-powerful microprocessors would let them stuff more signals into existing spectrum bandwidth. Jacobs initially won contracts from DARPA and NASA to build space communications systems. In the late 1980s, Qualcomm diversified into the civilian market, launching a satellite communications system for the trucking industry.

1985, Taiwan’s powerful minister K. T. Li called Morris Chang into his office in Taipei. Nearly two decades had passed since Li had helped convince Texas Instruments to build its first semiconductor facility on the island. In the twenty years since then, Li had forged close ties with Texas Instrument’s leaders, visiting Pat Haggerty and Morris Chang whenever he was in the U.S. and convincing other electronics firms to follow TI and open factories in Taiwan. In 1985, he hired Chang to lead Taiwan’s chip industry. “We want to promote a semiconductor industry in Taiwan,” he told Chang. “Tell me,” he continued, “how much money you need.”

After over two decades with Texas Instruments, Chang had left the company in the early 1980s after being passed over for the CEO job and “put out to pasture,” he’d later say. He spent a year running an electronics company in New York called General Instrument, but resigned soon after, dissatisfied with the work. He’d personally helped build the world’s semiconductor industry. TI’s ultra-efficient manufacturing processes were the result of his experimentation and expertise in improving yields. The job he’d wanted at TI—CEO—would have placed him at the top of the chip industry, on par with Bob Noyce or Gordon Moore.

Directing the Taiwanese government’s Industrial Technology Research Institute, the position that Chang was formally offered, would place him at the center of Taiwan’s chip development efforts. The promise of government financing sweetened the deal.

As early as the mid-1970s, while still at TI, Chang had toyed with the idea of creating a semiconductor company that would manufacture chips designed by customers. At the time, chip firms like TI, Intel, and Motorola mostly manufactured chips they had designed in-house.

The Taiwanese government provided 48 percent of the startup capital for TSMC, stipulating only that Chang find a foreign chip firm to provide advanced production technology.

Chang convinced Philips, the Dutch semiconductor company, to put up $58 million, transfer its production technology, and license intellectual property in exchange for a 27.5 percent stake in TSMC.

The rest of the capital was raised from wealthy Taiwanese who were “asked” by the government to invest. “What generally happened was that one of the ministers in the government would call a businessman in Taiwan,” Chang explained, “to get him to invest.”

The government also provided generous tax benefits for TSMC, ensuring the company had plenty of money to invest. From day one, TSMC wasn’t really a private business: it was a project of the Taiwanese state.

A crucial ingredient in TSMC’s early success was deep ties with the U.S. chip industry. Most of its customers were U.S. chip designers, and many top employees had worked in Silicon Valley.

1986, Japan had overtaken America in the number of chips produced. By the end of the 1980s, Japan was supplying 70 percent of the world’s lithography equipment.

America’s share—in an industry invented by Jay Lathrop in a U.S. military lab—had fallen to 21 percent. Lithography is “simply something we can’t lose, or we will find ourselves completely dependent on overseas manufacturers to make our most sensitive stuff,” one Defense Department official told the New York Times.

The U.S. military was more dependent on electronics—and thus on chips—than ever before. By the 1980s, the report found, around 17 percent of military spending went toward electronics, compared to 6 percent at the end of World War II.

1986, with the threat of tariffs looming, Washington and Tokyo cut a deal. Japan’s government agreed to put quotas on its exports of DRAM chips, limiting the number that were sold to the U.S. By decreasing supply, the agreement drove up the price of DRAM chips everywhere outside of Japan, to the detriment of American computer producers, which were among the biggest buyers of Japan’s chips. Higher prices actually benefitted Japan’s producers, which continued to dominate the DRAM market.

Most American producers were already in the process of exiting the memory chip market. So despite the trade deal, only a few U.S. firms continued to produce DRAM chips. The trade restrictions redistributed profits within the tech industry, but they couldn’t save most of America’s memory chip firms.

late 1980s, Samsung entered the business in licensed technology from Micron, opened an R&D facility in Silicon Valley, and hired dozens of American-trained PhDs. Another, faster, method for acquiring know-how is to poach employees and steal files.

1987, a group of leading chipmakers and the Defense Department created a consortium called Sematech, funded half by the industry and half by the Pentagon. Sematech was based on the idea that the industry needed more collaboration to stay competitive.

Equipment firms didn’t want to launch a new piece of machinery unless chipmakers were prepared to use it. Sematech helped them agree on production schedules.

Fifty-one percent of Sematech funding went to American lithography firms. Noyce explained the logic simply: lithography got half the money because it was “half the problem” facing the chip industry. It was impossible to make semiconductors without lithography tools, but the only remaining major U.S. producers were struggling to survive.

1989-An accidental fire in TSMC’s fab

caused TSMC to buy an additional nineteen new lithography machines from ASML, paid for by the fire insurance.

1990s, Taiwan’s importance began to grow, driven by the spectacular rise of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which Chang founded with strong backing from the Taiwanese government.

Morris Chang hired Don Brooks, another former Texas Instruments executive, to work as TSMC’s president from 1991 to 1997. “Most of the guys who reported to me, down two levels,” Brooks recalled, “all had some experience in the U.S… they all worked for Motorola, Intel, or TI.” Throughout much of the 1990s, half of TSMC’s sales were to American companies. Most of the company’s executives, meanwhile, trained in top doctoral programs at U.S. universities. This symbiosis benefitted Taiwan and Silicon Valley.

The founding of TSMC gave all chip designers a reliable partner. Chang promised never to design chips, only to build them. TSMC didn’t compete with its customers; it succeeded if they did.

A decade earlier, Carver Mead had prophesied a Gutenberg moment in chipmaking, but there was one key difference. The old German printer had tried and failed to establish a monopoly over printing. He couldn’t stop his technology from quickly spreading across Europe, benefitting authors and print shops alike. In the chip industry, by lowering startup costs, Chang’s foundry model gave birth to dozens of new “authors”—fabless chip design firms—that transformed the tech sector by putting computing power in all sorts of devices.

However, the democratization of authorship coincided with a monopolization of the digital printing press. The economics of chip manufacturing required relentless consolidation. Whichever company produced the most chips had a built-in advantage, improving its yield and spreading capital investment costs over more customers.

TSMC’s business boomed during the 1990s and its manufacturing processes improved relentlessly. Morris Chang wanted to become the Gutenberg of the digital era. He ended up vastly more powerful. Hardly anyone realized it at the time, but Chang, TSMC, and Taiwan were on a path toward dominating the production of the world’s most advanced chips.

1993-Nvidia was founded in 1993 by Chris Malachowsky, Curtis Priem, and Jensen Huang, the latter of whom remains CEO today.

Nvidia, had its humble beginnings not in a trendy Palo Alto coffeehouse but in a Denny’s in a rough part of San Jose.

Priem had done fundamental work on how to compute graphics while at IBM, then worked at Sun Microsystems alongside Malachowsky. Huang, who was originally from Taiwan but had moved to Kentucky as a child, worked for LSI, a Silicon Valley chipmaker. He became the CEO and the public face of Nvidia, always wearing dark jeans, a black shirt, and a black leather jacket, and possessing a Steve Jobs−like aura suggesting that he’d seen far into the future of computing.

Every PC maker, from IBM to Compaq, had to use an Intel or an AMD chip for their main processor, because these two firms had a de facto monopoly on the x86 instruction set that PCs required. There was a lot more competition in the market for chips that rendered images on screens.

Nvidia eventually came to dominate the market for graphics chips,

1996, Intel forged a partnership with several of the laboratories operated by the U.S. Department of Energy, which had expertise in optics and other fields needed to make EUV work. Intel assembled a half dozen other chipmakers to join the consortium, but Intel paid for most of it and was the “95 percent gorilla” in the room, one participant remembered. Intel knew that the researchers at Lawrence Livermore and Sandia National Labs had the expertise to build a prototype EUV system, but their focus was on the science, not on mass production.

Grove spent $200 million developing EUV lithography. Intel would eventually spend billions of dollars on R&D and billions more learning how to use EUV to carve chips.

The U.S. government required ASML to build a facility in the U.S. to manufacture components for its lithography tools and supply American customers and employ American staff. However, much of ASML’s core R&D would take place in the Netherlands.

Despite long delays and huge cost overruns, the EUV partnership slowly made progress. Locked out of the research at the U.S. national labs, Nikon and Canon decided not to build their own EUV tools, leaving ASML as the world’s only producer

1999, an earthquake measuring 7.3 on the Richter scale struck Taiwan, knocking out power across much of the country, including from two nuclear power plants. TSMC’s fabs lost power, too, threatening the company’s production and many of the world’s chips. Morris Chang was quickly on the phone with Taiwanese officials to ensure the company got preferential access to electricity. It took a week to get four of the company’s five fabs back online; the fifth took even longer.

[Personal note, because Morris wanted preferential treatment we suffered through several weeks of scheduled blackouts after the quake getting electricity only at scheduled times, so thanks Morris. My sister in law got rich buying TSMC stock though]

TSMC’s customers were told that the company’s facilities could tolerate earthquakes measuring 9 on the Richter scale, of which the world has experienced five since 1900.

2001, ASML bought SVG, America’s last major lithography firm. SVG already lagged far behind industry leaders, but again questions were raised about whether the deal suited America’s security interests.

Inside DARPA and the Defense Department, which had funded the lithography industry for decades, some officials opposed the sale. Congress raised concerns, too, with three senators writing President George W. Bush that “ASML will wind up with all of the U.S. government’s EUV technology.”

Intel and other big chipmakers argued that the sale of SVG to ASML was crucial to developing EUV—and thus fundamental to the future of computing. “Without the merger,” Intel’s new CEO Craig Barrett argued in 2001, “the development path to the new tools in the U.S. will be delayed.” With the Cold War over, the Bush administration, which had just taken power, wanted to loosen technology export controls on all goods except those with direct military applications.

The administration described the strategy as “building high walls around technologies of the highest sensitivity.” EUV didn’t make the list. The next-generation EUV lithography tools would therefore be mostly assembled abroad, though some components continued to be built in a facility in Connecticut.

The manufacturing of EUV wasn’t globalized, it was monopolized. A single supply chain managed by a single company would control the future of lithography.

2005, aged seventy-four, Morris Chang stepped down from the role of CEO, though he remained chairman of TSMC. Soon there’d be no one left who remembered working in the lab alongside Jack Kilby or drinking beers with Bob Noyce.

2006-Shortly after the deal to put Intel’s chips in Mac computers, Jobs came back to Otellini with a new pitch. Would Intel build a chip for Apple’s newest product, a computerized phone? All cell phones used chips to run their operating systems and manage communication with cell phone networks, but Apple wanted its phone to function like a computer. It would need a powerful computer-style processor as a result. “They wanted to pay a certain price,” Otellini told journalist Alexis Madrigal after the fact, “and not a nickel more…. I couldn’t see it.

Just a handful of years after Intel turned down the iPhone contract, Apple was making more money in smartphones than Intel was selling PC processors.

2006, realizing that high-speed parallel computations could be used for purposes besides computer graphics, Nvidia released CUDA, software that lets GPUs be programmed in a standard programming language, without any reference to graphics at all. Even

Huang gave away CUDA for free, but the software only works with Nvidia’s chips. By making the chips useful beyond the graphics industry, Nvidia discovered a vast new market for parallel processing, from computational chemistry to weather forecasting. At the time, Huang could only dimly perceive the potential growth in what would become the biggest use case for parallel processing: artificial intelligence.

Today Nvidia’s chips, largely manufactured by TSMC, are found in most advanced data centers.

2007-Five years after Sanders retired from AMD, the company announced it was dividing its chip design and fabrication businesses. Wall Street cheered, reckoning the new AMD would be more profitable without the capital-intensive fabs. AMD spun out these facilities into a new company that would operate as a foundry like TSMC,

The investment arm of the Abu Dhabi government, Mubadala, became the primary investor in the new foundry, an unexpected position for a country known more for hydrocarbons than for high-tech.

GlobalFoundries, as this new company that inherited AMD’s fabs. When GlobalFoundries was established as an independent company in 2009, industry analysts thought it was well placed to win market share amid this race toward 3D transistors. Even TSMC was worried, the company’s former executives admit. GlobalFoundries had inherited a massive fab in Germany and was building a new, cutting-edge facility in New York.

2009-Amid the financial crisis, Chang’s handpicked successor, Rick Tsai, had done what nearly every CEO did—lay off employees and cut costs. Chang wanted to do the opposite. Getting the company’s 40nm chipmaking back on track required investing in personnel and technology. Trying to win more smartphone business—especially that of Apple’s iPhone, which launched in 2007 and which initially bought its key chips from TSMC’s archrival, Samsung—required massive investment in chipmaking capacity. Chang saw Tsai’s cost cutting as defeatist. “There was very, very little investment,” Chang

So Chang fired his successor and retook direct control of TSMC. So at the depths of the crisis Chang rehired the workers the former CEO had laid off and doubled down on investment in new capacity and R&D. He announced several multibillion-dollar increases to capital spending in 2009 and 2010 despite the crisis. It was better “to have too much capacity than the other way around,”

2010, at the time Apple launched its first chip, there were just a handful of cutting-edge foundries: Taiwan’s TSMC, South Korea’s Samsung, and—perhaps—GlobalFoundries, depending on whether it could succeed in winning market share. Intel, still the world’s leader at shrinking transistors, remained focused on building its own chips for PCs and servers rather than processors for other companies’ phones.

For PCs, most processors come from Intel and are produced at one of the company’s fabs in the U.S., Ireland, or Israel. Smartphones are different. They’re stuffed full of chips, not only the main processor (which Apple designs itself), but modem and radio frequency chips for connecting with cellular networks, chips for WiFi and Bluetooth connections, an image sensor for the camera, at least two memory chips, chips that sense motion (so your phone knows when you turn it horizontal), as well as semiconductors that manage the battery, the audio, and wireless charging. These chips make up most of the bill of materials needed to build a smartphone.

Today, no company besides TSMC has the skill or the production capacity to build the chips Apple needs. So the text etched onto the back of each iPhone—“Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China”—is highly misleading. The iPhone’s most irreplaceable components are indeed designed in California and assembled in China. But they can only be made in Taiwan.

2010s, Nvidia—the designer of graphic chips—began hearing rumors of PhD students at Stanford using Nvidia’s graphics processing units (GPUs) for something other than graphics. GPUs were designed to work differently from standard Intel or AMD CPUs, which are infinitely flexible but run all their calculations one after the other. GPUs, by contrast, are designed to run multiple iterations of the same calculation at once. This type of “parallel processing,” it soon became clear, had uses beyond controlling pixels of images in computer games. It could also train AI systems efficiently. Where

From its founding, Nvidia outsourced its manufacturing, largely to TSMC, and focused relentlessly on designing new generations of GPUs and rolling out regular improvements to its special programming language called CUDA that makes it straightforward to devise programs that use Nvidia’s chips.

2012, years before ASML had produced a functional EUV tool, Intel, Samsung, and TSMC had each invested directly in ASML to ensure the company had the funding needed to continue developing EUV tools that their future chipmaking capabilities would require. Intel alone invested $4 billion in ASML in 2012, one of the highest-stakes bets the company ever made,

ASML had set a target for each component to last on average for at least thirty thousand hours—around four years—before needing repair. In practice, repairs would be needed more often, because not every part breaks at the same time. EUV machines cost over $100 million each, so every hour one is offline costs chipmakers thousands of dollars in lost production.

That a Dutch company, ASML, had commercialized a technology pioneered in America’s National Labs and largely funded by Intel would undoubtedly have rankled America’s economic nationalists, had any been aware of the history of lithography or of EUV technology. Yet ASML’s EUV tools weren’t really Dutch, though they were largely assembled in the Netherlands. Crucial components came from Cymer in California and Zeiss and Trumpf in Germany. And even these German firms relied on critical pieces of U.S.-produced equipment. The point is that, rather than a single country being able to claim pride of ownership regarding these miraculous tools, they are the product of many countries. A tool with hundreds of thousands of parts has many fathers.

2015, GlobalFoundries was by far the biggest foundry in the United States and one of the largest in the world, but it was still a minnow compared to TSMC. GlobalFoundries competed with Taiwan’s UMC for status as the world’s second-largest foundry, with each company having about 10 percent of the foundry marketplace. However, TSMC had over 50 percent of the world’s foundry market.

Measured by thousands of wafers per month, the industry standard, TSMC had a capacity of 1.8 million while Samsung had 2.5 million. GlobalFoundries had only 700,000.

2015- China’s Jinhua cut a deal with Taiwan’s UMC, which fabricated logic chips (not memory chips), whereby UMC would receive around $700 million in exchange for providing expertise in producing DRAM. Licensing agreements are common in the semiconductor industry, but this agreement had a twist. UMC was promising to provide DRAM technology, but it wasn’t in the DRAM business. So in September 2015, UMC hired multiple employees from Micron’s facility in Taiwan, starting with the president, Steven Chen, who was put in charge of developing UMC’s DRAM technology and managing its relationship with Jinhua.

UMC hired a process manager at Micron’s Taiwan facility named J. T. Ho. Over the subsequent year, Ho received a series of documents from his former Micron colleague, Kenny Wang, who was still working at the Idaho chipmaker’s facility in Taiwan. Eventually, Wang left Micron to move to UMC, bringing nine hundred files uploaded to Google Drive with him.

Efforts by the Obama administration to cut a deal with China’s spy agencies whereby they agreed to stop providing stolen secrets to Chinese companies lasted only long enough for Americans to forget about the issue, at which point the hacking promptly restarted.

Some administration officials advocated imposing financial sanctions on Jinhua, using powers set out in an executive order on cyber espionage signed by President Obama in 2015, though the order hadn’t been used against a major Chinese company.

2018, GlobalFoundries had purchased several EUV lithography tools and was installing them in its most advanced facility, Fab 8, when the company’s executives ordered them to halt work. The EUV program was being canceled. GlobalFoundries was giving up production of new, cutting-edge nodes. It wouldn’t pursue a 7nm process based on EUV lithography, which had already cost $1.5 billion in development and would have required a comparable amount of additional spending to bring online.

Even the deep pockets of the Persian Gulf royals who owned GlobalFoundries weren’t deep enough. The number of companies capable of fabricating leading-edge logic chips fell from four to three.

2019-DARPA has funded a variety of projects related to developing RISC-V. Chinese firms have also embraced RISC-V, because they see it as geopolitically neutral. In 2019, the RISC-V Foundation, which manages the architecture, moved from the U.S. to Switzerland for this reason.

One of China’s core challenges today is that many chips use either the x86 architecture (for PCs and servers) or the Arm architecture (for mobile devices); x86 is dominated by two U.S. firms, Intel and AMD, while Arm, which licenses other companies to use its architecture, is based in the UK. However, there’s now a new instruction set architecture called RISC-V that is open-sourced, so it’s available to anyone without a fee. The idea of an open-source architecture appeals to many parts of the chip industry. Anyone who currently must pay Arm for a license would prefer a free alternative. Moreover, the risk of security defects may be lower,

2020, half of all EUV lithography tools, funded and nurtured by Intel, were installed at TSMC. By contrast, Intel had only barely begun to use EUV in its manufacturing process.

Since 2015, Intel has repeatedly announced delays to its 10nm and 7nm manufacturing processes, even as TSMC and Samsung have charged ahead.

2022-TSMC retains its central role in the world’s chip industry. The company itself plans to invest over $100 billion between 2022 and 2024 to upgrade its technology and expand chipmaking capacity. Most of this money will be invested in Taiwan, though the company plans to upgrade its facility in Nanjing, China, and to open a new fab in Arizona.

Three companies dominate the world’s market for DRAM chips today, Micron and its two Korean rivals, Samsung and SK Hynix

The DRAM market requires economies of scale, so it’s difficult for small producers to be price competitive. Though Taiwan never succeeded in building a sustainable memory chip industry, both Japan and South Korea had focused on DRAM chips when they first entered the chip industry in the 1970s and 1980s. DRAM requires specialized know-how, advanced equipment, and large quantities of capital investment.

In 2018 after Jinhua paid invoices to the U.S. firms that supplied its crucial chipmaking tools, the U.S. banned their export. Within months, production at Jinhua ground to a halt. China’s most advanced DRAM firm was destroyed.

U.S. companies like Applied Materials, Lam Research, and KLA are part of a small oligopoly of companies that produce irreplaceable machinery, like the tools that deposit microscopically thin layers of materials on silicon wafers or recognize nanometer-scale defects. Without this machinery—much of it still built in the U.S.—it’s impossible to produce advanced semiconductors. Only Japan has companies producing some comparable machinery, so if Tokyo and Washington agreed, they could make it impossible for any firm, in any country, to make advanced chips.

Nearly every chip in the world uses software from at least one of three U.S.-based companies, Cadence, Synopsys, and Mentor (the latter of which is owned by Germany’s Siemens but based in Oregon). Excluding the chips Intel builds in-house, all the most advanced logic chips are fabricated by just two companies, Samsung and TSMC, both located in countries that rely on the U.S. military for their security.

Moreover, making advanced processors requires EUV lithography machines produced by just one company, the Netherlands’ ASML, which in turn relies on its San Diego subsidiary, Cymer (which it purchased in 2013), to supply the irreplaceable light sources in its EUV lithography tools.

TSMC can’t fabricate advanced chips without using U.S. manufacturing equipment. Huawei can’t design chips without U.S.-produced software. Even China’s most advanced foundry, SMIC, relies extensively on U.S. tools.

Many of China’s biggest tech companies, like Tencent and Alibaba, still face no specific limits on their purchases of U.S. chips or their ability to have TSMC manufacture their semiconductors. SMIC, China’s most advanced producer of logic chips, faces new restrictions on its purchases of advanced chipmaking tools, but it has not been put out of business. Even Huawei is allowed to buy older semiconductors, like those used for connecting to 4G networks.

Yangzte Memory Technologies Corporation (YMTC), based in Wuhan, is China’s leading producer of NAND memory, a type of chip that’s ubiquitous in consumer devices from smartphones to USB memory sticks. There are five companies that make competitive NAND chips today; none are headquartered in China. Many industry experts, however, think that of all types of chips, China’s best chance at achieving world-class manufacturing capabilities is in NAND production.

Dan Wang, one of the smartest analysts of China’s tech policy, has argued that American restrictions have “boosted Beijing’s quest for tech dominance” by catalyzing new government policies to support the chip industry. In the absence of America’s new export controls, he argues, Made in China 2025 would have ended up like China’s previous industrial policy efforts, with the government wasting substantial sums of money. Thanks to U.S. pressure, China’s government may provide Chinese chipmakers more support than they’d otherwise have received.

U.S. wants to reverse its declining share of chip fabrication and retain its dominant position in semiconductor design and machinery. Countries in Europe and Asia, however, would like to grab a bigger share of the high-value chip design market. Taiwan and South Korea, meanwhile, have no plans to surrender their market-leading positions fabricating advanced logic and memory chips. With China viewing expansion of its own fabrication capacity as a national security necessity, there’s a limited amount of future chip fabrication business that can be shared between the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

End Timeline

If the U.S. wants to increase its market share, some other country’s market share must decrease.

At some point, Taiwan becomes a strategic competitor as the US attempt to increase market share in the wake of the CHIPS ACT.

Under the CHIPS Act, the U.S. government will inject US$52.7 billion into the American semiconductor industry to shore up its manufacturing and research/development strength. Funding will include US$39 billion in subsidies provided to companies to build new facilities and expand production capacity in the U.S.

According to a recent report from Reuters, the Department of Commerce (DOC) is planning to take applications in late June from the companies who eye the subsidies.

On Tuesday, the DOC announced the so-called National Security Guardrails, which will ban recipients of U.S. government subsidies from investing in most semiconductor manufacturing in foreign adversary countries for 10 years after the date of being awarded funding. The DOC named China, Russia, Iran and North Korea as the adversary countries against the U.S. or its allies and partners.

TSMC is building fabs in the U.S. state of Arizona that will make chips using the 4 nanometer and 3nm processes, with mass production scheduled to begin in 2024 and 2026. The DOC official declined to comment on whether TSMC is seeking subsidies from the U.S. government.

In addition to TSMC, Taiwan-based GlobalWafers Co. has begun construction of a 12-inch silicon wafer plant in Texas, with the aim of beginning mass production in 2024. The investment project was launched after the passage of the CHIPS Act.

https://focustaiwan.tw/business/202303220009

The Biden administration unveiled rules Tuesday for its “Chips for America” program to build up semiconductor research and manufacturing in the United States, beginning a new rush toward federal funding in the sector.

The Commerce Department has $50 billion to hand out in the form of direct funding, federal loans and loan guarantees. It is one of the largest federal investments in a single industry in decades and highlights deepening concern in Washington about America’s dependence on foreign chips.

Given the huge cost of building highly advanced semiconductor facilities, the funding could go fast, and competition for the money has been intense.

Here’s a look at the CHIPS and Science Act, what it aims to do and how it will work.

Funding chip production and research

The largest portion of the money— $39 billion — will go to fund the construction of new and expanded manufacturing facilities. Another $11 billion will be distributed later this year to support research into new chip technologies.

The bulk of the manufacturing money is likely to go to a few companies that produce the world’s most advanced semiconductors — including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Samsung Electronics, Micron Technology and, perhaps in the future, Intel — to help them build U.S. facilities.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/28/business/economy/chips-act-childcare.html

Note: By getting Samsung ,TSMC, etc to build facilities in US and send skilled staff to operate them companies like Intel can more easily poach these employees and use them to set up and operate their own facilities

TAIPEI (Taiwan News) — Nvidia announced on Tuesday (March 21) that it has partnered with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), ASML, and Synopsys to promote the use of its software library for computational lithography.

Nvidia’s new “cuLitho” software library for computational lithography will allow its partners to speed up the design and manufacturing of next-gen chips, according to Nvidia. Computational lithography is the use of mathematical pre-processing of a photomask file to adjust for aberrations and effects in optical lithography, according to eeNews Europe.

According to Nvidia, the advance will allow for chips with smaller transistors and wires than is now achievable, while also speeding up time to market and increasing energy efficiency of data centers to drive the manufacturing process. The computation underlying the lithographic patterning of advanced ICs can be made 40 times more efficient by running it on GPUs instead of general-purpose CPUs

Fabs using cuLitho can produce three to five times more photomasks (templates for a chip’s design) per day, while using nine times less power than current setups, according to Nvidia. Meanwhile, a photomask that used to take two weeks can now be processed overnight, Nvidia added.

“With lithography at the limits of physics, Nvidia’s introduction of cuLitho and collaboration with our partners TSMC, ASML, and Synopsys allows fabs to increase throughput, reduce their carbon footprint and set the foundation for 2nm and beyond,” said Jensen Huang (黃仁勳), CEO and founder of Nvidia.

https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/4843377

Miller goes on to talk about Trumps Trade War with China that continues today and the impacts of a possible War with China. This is already too long so I wont go into that. You will have to read the book. However, while he does a good job pointing out the US advatages over China and its control of many choke points in the semiconductor industry, he does not mention the US and Taiwans reliance on China and Russia for raw materials. Excerpts from a few articles follows.

Russia and Ukraine are major producers of two key materials used in semiconductor manufacturing: neon and palladium. Ukraine represents about 70 to 80 percent of the global supply of neon1, and Russia produces about 35 to 45 percent of the world’s palladium supply2.

Neon: Neon is used in the deep-ultraviolet lithography process in semiconductor manufacturing, which accounts for about 45 percent of neon demand3. Neon is a byproduct of older types of steel plants, which still exist in Ukraine but have been phased out elsewhere (which is why supply is so concentrated). Technically, neon can be recycled and reused4. Not all semiconductor firms have made the investment to do so, preferring to stockpile the gas — despite the warning signs seen after the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, when neon prices spiked by 600 percent5.

Palladium: The palladium supply is less exposed to the war, but shortages could affect both semiconductor production and demand. Palladium is used in plating applications in semiconductor production and is essential for catalytic converters. Automakers that can’t produce vehicles because of catalytic converter shortages would also reduce chip orders.

https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2022/08/semiconductor-considerations.html

China produces over one-third of essential components imported into the U.S. for building technology goods, said John VerWey, East Asia national security advisor at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. VerWey was speaking during a hearing on U.S. and China competition in global supply chains held by the U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission.

"Chinese firms maintain monopolies or near monopolies in many critical technology supply chain segments," VerWey said during the hearing. "Particularly in raw materials, mining, refining and processing, where in some cases, U.S. reliance is 100%."

The U.S. could also consider mining raw materials for chips, which would improve supply chain resilience, VerWey said.

However, establishing a mining site can take years due to regulatory requirements from agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency, and mining sites can often run into environmental issues that prevent them from coming online.

"The U.S. has abundant raw material resources," VerWey said. "But increasing domestic mining and refining capacity has long wait times, is costly and comes with tradeoffs."

China remains a leader in mining of the raw materials, rare earth elements, used for semiconductors, said Kristin Vekasi, associate professor in the School of Policy and International Affairs at the University of Maine.

The Russian government has reportedly restricted the export of noble gases including neon, a major ingredient used for manufacturing semiconductor chips. Analysts noted that such move may impact the global supply chain of chips, and aggravate market supply bottleneck.

The restriction is a response to the fifth round of sanctions imposed by the EU in April, RT reported on June 2, citing a government decree stating that the export of noble and others through December 31 in 2022 will be subject to Moscow approval based on the recommendation of the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

RT reported that noble gases such as neon, argon, xenon, and others are crucial for semiconductor manufacturing. Russia supplies up to 30 percent of the neon consumed globally, RT reported, citing the newspaper Izvestia.

According to a China Securities research report, the restrictions will possibly exacerbate the supply shortage of chips in the global market and further increase prices. The impact of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict on the semiconductor supply chain is growing with the upstream raw material segment bearing the brunt.

As China is the world's largest chip consumer and highly dependent on imported chips, the restriction might affect the country's domestic semiconductor manufacturing, Xiang Ligang, director-general of the Beijing-based Information Consumption Alliance, told the Global Times on Monday.

Xiang said that China imported around $300 billion worth of chips in 2021, used for producing cars, smartphones, computers, televisions and other smart devices.

The China Securities report said that neon, helium and other noble gases are indispensable raw materials for semiconductor manufacturing. For instance, neon plays a vital role in the refinement and stability of the engraved circuit and chip making process.

Previously, Ukrainian suppliers Ingas and Cryoin, which supply about 50 percent of the world's neon gas for semiconductor uses, stopped production due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the global price of neon and xenon gas has kept going up.

As for the exact impact on Chinese enterprises and industries, Xiang added it will depend on the detailed implementation process of specific chips. Sectors which highly rely on imported chips may be affected more significantly, whereas the impact will be less noticeable on industries adopting chips that can be produced by Chinese companies such as SMIC.

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202206/1267382.shtml

China is also the world’s largest producer of aluminum, at 36 million tons. The US only rates number nine in the global producer ranking. China is also the world’s main supplier of tungsten; the third largest producer of tungsten is Russia, China’s ally.

There’s a similar story with China’s monopoly of materials for lithium batteries, the power source of all those electric vehicles the Bidens want us to buy; while China produces more than 95% of the world’s raw gallium, the metal used in making chipsets for electronic devices such as computer motherboards or portable phones.

There are more than 30 types of semiconductor product categories, each optimized for a particular function in an electronic subsystem. Fabrication then typically requires as many as 300 different inputs, including raw wafers, commodity chemicals, specialty chemicals, and bulk gases. These inputs are processed by more than 50 classes of highly engineered precision equipment.

80% or more of the rare gases krypton and xenon used in the chip industry are purchased from Ukraine and China. Ukraine sourced many of those rare gases from Russia, which is also a major source of chlorofluorocarbons and helium.

On a geopolitical level, China controls about 80% of the mining production of tungsten, with 95% of supply controlled by one Chinese company, while 45-50% of global palladium supply comes from Russia.

https://topics.amcham.com.tw/2022/08/the-vast-and-vulnerable-semiconductor-supply-chain/

There are other areas of concern with reliance on Taiwan besides the threat of War and Earthquakes. That is Labor and Power Supply

In May, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) announced plans to hire more than 8,000 personnel, while in June U.S.-based memory chipmaker Micron, already Taiwan’s largest foreign employer with around 10,000 employees, announced plans to add a further 2,000 to its ranks. And it’s not just the foundries that are hiring, but many companies along the supply chain. ASE Technology, the world’s largest IC packaging and testing services provider, last September announced plans to hire over 2,000 staff for its Kaohsiung production base.

The Taiwan government is aware of the industry’s talent needs and has set up four dedicated colleges in partnership with industry heavyweights at local universities around Taiwan. Such a measure, while helpful, will likely not be enough, as Taiwan’s declining birthrate is expected to cause a sharp drop in university enrollments in the coming years. As the White Paper points out, more qualified foreigners will need to be brought in to fill the gap. Given that the shortage of skilled and qualified professionals extends globally, targeting students from abroad to train locally in Taiwan will also need to be a priority.

In Taiwan, there is also considerable anxiety regarding the most basic of inputs – electricity and water – says John Lee, managing director of Merck Group Taiwan. “The consistency and quality of the supply of power and water will be very crucial to overall industry development,” he says, given that the industry requires vast quantities of both, and demand is rising faster than the government anticipated. Last year’s drought was a wake-up call for the industry, as were the multiple rolling blackouts that have occurred since last May, as well as record-breaking electricity usage that is straining the state-owned Taiwan Power Co.’s reserve capacity. Delays in building a liquefied natural gas terminal and in expanding offshore wind capacity, combined with the government’s plans to end the use of nuclear power by 2025 and to shutter some coal units at the Taichung Power Plant, suggest that supply will be tight for the foreseeable future.

https://topics.amcham.com.tw/2022/08/the-vast-and-vulnerable-semiconductor-supply-chain/

I have talked about Taiwans birth decline and excess deaths elsewhere, and its rapidly aging population. This can be solved with immigration, but politically this will prove to be unpopular.

Taipei, March 13 (CNA) The planned shutdown of the No. 2 generator at Taiwan's second power plant on Tuesday could result in power shortages and must be reversed, an energy scholar and opposition lawmaker warned on Tuesday.

The generator -- the last of two at the nuclear plant in New Taipei's Jinshan District -- is due to be decommissioned Tuesday upon the expiration of its 40-year operating permit, in line with the government's goal of phasing out nuclear power by 2025.

Economics Minister Wang Mei-hua (王美花), who oversees the state-run Taiwan Power Co. (Taipower), has maintained that Taiwan will be able to offset the loss of the generator, which provides around 3 percent of Taiwan's energy supply, using hydroelectric power.

While hydroelectric and pumped-storage hydroelectric sources accounted for a similar amount of power generation last year -- a combined 8.89 billion kilowatt hours, or just over 3 percent of the total energy mix, according to the Bureau of Energy -- it is unclear whether that could directly replace the lost capacity from the generator.

https://focustaiwan.tw/politics/202303130021

Well, it rains a lot in Taiwan, or at least it used to but in recent years the climate is changing , and not for the better IMO. I sometimes suspect China is modifying the weather and reducing rainfall, and maybe US is doing something similar to protect Taiwan from typhoons (which do cause damage but also bring a lot of water) . Whatever, this winter has been especially dry

2023-03-07

Forecasters say no significant rainfall is expected until May as reservoirs dry up

Water levels at reservoirs in Southern Taiwan continue falling, with Tsengwen reservoir hitting a low 18% capacity. The Central Weather Bureau says the past three months have been the driest in the last 60 years for areas south of Taoyuan. Meteorologists say they expect the spring season to be drier and warmer than usual, warning that rains may not come until May, with the plum rain season.

https://english.ftvnews.com.tw/news/2023307W01EA

Potentially facing worst drought in 30 years

https://en.rti.org.tw/news/view/id/2009076

Oh well, don’t worry, TSMC will get its juice while we roast in the summer heat.