A look back at the disease and the Vaccine

In 1717 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu returned to England from the Ottoman Empire with knowledge of a practice called variolation, which entailed taking a small amount of material from a human smallpox lesion and scratching it into the skin of another person.

If all went well, the recipient would suffer a mild attack of smallpox and then become immune to the disease.

Two problems with variolation were that it could result in death (3% FR vs 10-18% natural infection) and the procedure spread disease into surrounding communities. In 1721, 6% of deaths were from Smallpox.

Since the late 1700s, the medical profession has supported vaccination, even though there was never a trial where one group was vaccinated and compared to another group of the same size that was not vaccinated.

In Thomas Malthus 1798 book An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus argued that two types of checks hold population within resource limits: positivechecks, which raise the death rate; and preventiveones, which lower the birth rate.

The positive checks include hunger, disease and war; the preventive checks: birth control, postponement of marriage and celibacy

Malthus had initially recommended filthy conditions for the poor, crowding more people into houses/cities, and bringing back the plague.

Also holding back treatment and cures for diseases to reduce population

Later he emphasized more positive measures to control population

I bring up Malthus because in a 2010 Ted Talk Bill Gates said if we do Vaccines right we can reduce Population Growth (projected to grow from 6.8 to 9 billion) by 10-15%

In the same year we coincidentally have Edward Jenner publishing a small booklet entitled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox. Jenner decided to call this new procedure vaccination.

Jenners claims in 1798 were based on a small sample and no control, and basically no scientific method, and it fueled the belief that once a person was exposed to cowpox, lifelong protection from smallpox was possible.

Jenner’s claim was later replaced with varying estimates from 10 years to as little as 1 year. A 1908 article concluded that some limited immunity lasted only around three years. …

Another practitioner named Dr. Olesen claimed that revaccination should be done annually. Protection lasts from six months to twelve months and often much longer. Revaccination is advisable once a year.

Because of the confusion regarding what was in the vaccines, the material used for vaccination was sometimes referred to as “vaccine virus.”

The first Vaccination Act in England was passed in 1840; it outlawed variolation (i.e., the practice of infecting a person with actual smallpox) and provided vaccination that used vaccines developed from cow pox or vaccinia virus free of charge.

When it was clear that the smallpox vaccine was not able to prevent disease, the medical profession tried to justify vaccination by changing the goalposts from lifelong “perfect” immunity to “milder disease.”

Similar dogma was repeated in 2013 to justify the fact that pertussis and influenza vaccines don’t protect recipients either, and now COVID vaccines

But did smallpox vaccination really decrease the death rate and make for a milder disease? In the 1844 smallpox epidemic, about one-third of the vaccinated contracted a mild form of smallpox, but roughly 8 percent of those vaccinated still died, and nearly two-thirds had severe disease.

A letter to a newspaper in 1850 claimed there were more admissions to the London Small-Pox Hospital in 1844 than during the smallpox epidemic of 1781 before vaccination began. The author also noted that one-third of the deaths from smallpox were in people who had previously been vaccinated.

Deaths as a result of vaccination were often not reported because of an allegiance to the practice. Often a vaccinated person was recorded as having died from another condition or erroneously listed as unvaccinated, which must have had a considerable impact on the validity of the statistics of the day.

During the 1840’s, as doctors and citizens realized that vaccination was not what it was promised to be, vaccine refusals increased.

The 1853 Act made vaccination manda-tory and included measures to punish parents or guardians

In 1867 a harsher vaccination act was passed requiring vaccination within 3 months of birth

Large-scale popular resistance began after the 1867 Act with its threat of coercive cumulative penalties.

It is not correct to portray antivaccinationists indiscriminately as antirational, antimodern, and antiscientific.

Just considering the details of the vaccination practice of the mid-19th century does much to make many criticisms understandable. For instance, the widespread arm-to-arm vaccination, used until 1898, carried substantial risks, and the instruments used could contribute to severe adverse reactions.

Furthermore, many antivaccinationists appealed, like their opponents, to enlightenment values and expertly used quantitative arguments.

The 1871 Act authorized the appointment of vaccination officers, whose task it was to identify cases of noncompliance.

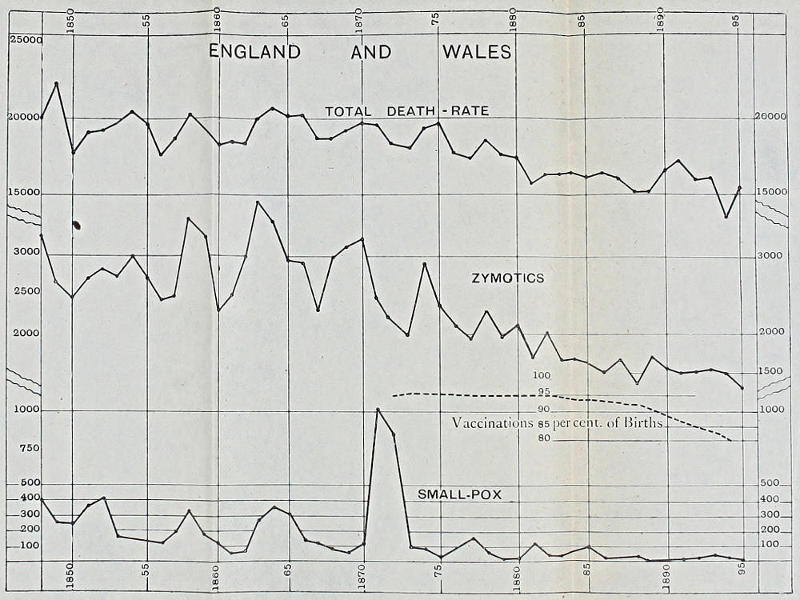

Smallpox epidemic 1870-1872 in England and Wales killed 44,000 persons despite 97% of people over 2 and under 50 being vaccinated or having had small pox before

The Public Health Act of 1875 improved Sanitation

After 1872, vaccination coverage rates slowly declined from a high of nearly 90 percent. Coverage rates plummeted to only 40 percent by 1909 . Despite declining vaccination rates, smallpox deaths remained low, vanishing to near zero after 1906.

Coincidentally or not the death rate for smallpox declined after 1872,

After the 1872 pandemic, even more people lost confidence in vaccination. They began asking the question as to whether better sanitation, hygiene, improved housing, nutrition, and isolation of cases were the best ways to deal with smallpox.

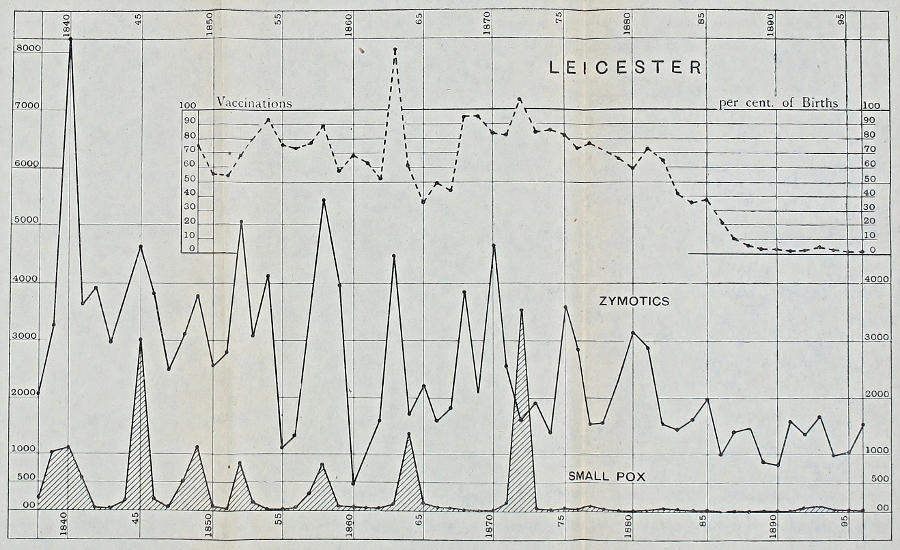

These ideas, which clashed with the medical profession and governmental laws, culminated in a large demonstration in 1885 against compulsory vaccination in the small manufacturing town of Leicester, England.

The public backlash culminated in the Great Demonstration in Leicester, England, in 1885. That same year, Leicester’s government, which had pushed for vaccination through the use of fines and jail time, was replaced with a new government that was opposed to compulsory vaccination.

By 1887 the vaccination coverage rates had dropped to 10 percent. Since 1885, there had been no prosecution, and last year (1887), he believed, the number of vaccinations in Leicester amounted to only 11 and 12 per cent of births.

The “Leicester Method” relied on quarantine of smallpox patients and thorough disinfection of their homes. They believed this was a cheap and effective means to eliminate the need for vaccination.

An 1855 paper, On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species, is Alfred Russel Wallace’s first formal statement of his understanding of the process of biological evolution.

In this paper, he derives the law that “every species has come into existence coincident both in time and space with pre-existing closely allied species.”

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/4/pdfs/09-0434.pdf

In February 1858, while having a severe malaria attack, Wallace connected the ideas of Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) on the regulation of populations with his earlier reasoning and developed a concept that was similar to Darwin’s mechanism of natural selection.

Eager to share his discovery, Wallace wrote an essay on the subject as soon as he had recovered and sent it off to Darwin.

This innocent act by Wallace set off the well-known and often recounted story of Darwin’s hurried writing and publica- tion of On the Origin of Species.

Wallace returned to England in 1862 after the initial storm of reaction to Darwin’s theory had blown over. Together with Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895), he be- came one of the most vocal defenders of the theory of evo- lution.

So why don’t we know as much about Wallace as Darwin? Read on

In works such as Vaccination Proved Useless and Dangerous (1889) or Vaccination a Delusion, Its Penal Enforcement a Crime (1898), Wallace mounted his attack on several claims:

1) that death from smallpox was lower for vaccinated than for unvaccinated populations;

2), that the attack rate was lower for vaccinated populations: and

3) that vaccination alleviates the clinical symptoms of smallpox.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/58918/pg58918-images.html

Wallace concluded from his analysis that smallpox mortality rates increased with vaccination coverage, whereas his opponents concluded the exact opposite.

Wallace argued that the problem of determining vaccination status was serious and undermined the claims of his opponents. He asserted that the physicians’ belief in the efficacy of vaccination led to a bias in categorizing persons on the basis of interpretation of true or false vaccination scars. Additionally, epidemiologic data for vaccination status were seriously incomplete.

Depending on the sample, the vaccination status of 30%– 70% of the persons recorded as dying from smallpox was unknown (contrary to popular opinion hospitals dont always know vax status of COVID patients and inclined or incentivized to classify them as unvaxxed)

Furthermore, if a person contracted the disease shortly after a vaccination, it was often entirely unclear if the patient should be categorized as vaccinated or unvaccinated (gee whiz, sounds familiar)

Provaccinationists argued that the error introduced by this ambiguity was most likely to be random and thus would not affect the estimate of the efficiency of the vaccine.

In contrast, Wallace believed that doctors would have been more willing to report a death from smallpox in an unvaccinated patient and that this led to a serious bias and an overestimation of vaccine efficiency (sounds familiar)

Wallace’s holistic conception of health influenced his argument as well. He was convinced that susceptibility to the disease of smallpox was not distributed equally across social classes.

Weakened, poor persons living in squalor (and most at risk of getting smallpox) were in his opinion less likely to get vaccinated.

At the same time they would have higher smallpox mortality rates because their living conditions made them more susceptible to the disease.

He supported his hypothesis that susceptibilities differ with the observation that the mortality rate of unvaccinated persons had increased to 30% after the introduction of vaccination, while the vaccinated had enjoyed a slight survival advantage.

This demonstrated to Wallace that factors other than vaccination must have played a major role.

Wallace also makes some very interesting points in his Summary that have parallels to today

I. Why Doctors are not the Best Judges of the Results of Vaccination.

(1) In the first place they are interested parties, both pecuniarily and in a much greater degree on account of professional training and prestige. Only three years after vaccination was first introduced, on the recommendation of the heads of the profession, and their expressed conviction that it would give lifelong protection against a terrible disease, Parliament voted Jenner £10,000 in 1802, and £20,000 more in 1807, besides endowing vaccination with £3,000 a year in 1808.

From that time doctors as a body were committed to its support; it has been taught for nearly a century as an almost infallible remedy in all our medical schools; and has been for the most part accepted by the public and the legislature as if it were a well-established scientific principle, instead of being as the historian of epidemic diseases--Dr. Creighton--well terms it, a grotesque superstition.

(2) Whether vaccination produces good or bad results can only be determined by its effects on a large scale. We must see whether, during epidemics --at different periods or in different places--small-pox mortality is diminished as compared with that from other diseases in proportion to the total amount of vaccination; and this can be done only by the Statistician, using the best materials--in this country those of our Registrar-Generals.

Two of the greatest medical authorities on vaccination, Sir John Simon and Dr. Guy, F.R.S., have declared this to be necessary. The former, in 1857, in a Parliamentary Report on the History and Practice of Vaccination, says: "From individual cases the appeal is to masses of national experience."

Dr. Guy, in a celebrated paper published by the Royal Statistical Society, says: "Is vaccination a preventive of small-pox? To this question there is, there can be, no answer except such as is couched in the language of figures."

The language of figures is "Statistics"; hence, statisticians, not doctors, are the only good judges of this question. But the last Royal Commission consisted wholly of doctors, lawyers, politicians and country gentlemen, not one trained statistician!

Hence, as I have demonstrated in my Vaccination a Delusion, they have made the grossest blunders and their Report is absolutely worthless.

II. What is Proved by the Best Statistical Evidence Available.

(1) The only complete and trustworthy records of mortality and of the causes of death which we possess, are those of the Registrar-Generals for England and Wales, for Scotland and for Ireland; the former from 1838, the two latter from later dates.

But for London we have records from a much earlier period--the Bills of Mortality, which, though not completely accurate, are yet considered to show the rise and fall of the death-rates from the chief diseases then recognised, with sufficient general accuracy to be very valuable.

They are continually appealed to in order to show the enormous improvement in the health of London in the nineteenth as compared with the eighteenth century, and this comparison as regards small-pox is one of the stock arguments of the doctors, and was strongly urged by the Royal Commissioners.

It is stated over and over again that, down to the year 1800, small-pox deaths were excessive, but that from the very introduction of vaccination in 1800 they began to decrease, and have been getting less and less ever since. No other disease, it is said, has decreased in the same striking manner.

(2) This being the very foundation of the supposed evidence in favour of vaccination it is necessary to examine it closely, when it will be found to be wholly worthless, and to illustrate in a striking manner the complete ignorance of doctors, and also of the Royal Commissioners, of the very elements of statistical enquiry.

This requires some little explanation, though it is really a very simple matter.

In order to be able to study the effect of any alleged cause of improved health of the community, we must compare the death-rates before and after the introduction of the supposed cause of improvement (in this case vaccination), and also compare these with the death-rates from other groups of diseases, and from all causes.

These facts are given by the Registrar-General in tables showing the number of deaths each year in each million of the population. Now, small-pox, many fevers, cholera, etc. are what are termed epidemic diseases, which attack large populations at irregular intervals with great severity, while at other times they are far less fatal or more local.

Hence the yearly death-rates vary enormously. In 1796 more than 4,000 per million died of small-pox in London, while in the next year there were only about 800, and the following year (1798) over 3,000.

Again, in 1870 less than 100 per million died of it, while in 1871 there were about 300, and in 1872 about 2,500. Thus the figures go increasing and decreasing so suddenly and so irregularly, that by taking only a few years at one period, and a few at another, you can show an increase or a decrease according to what you wish to prove.

Hence it is often ignorantly said that figures can be made to prove anything. But this is quite untrue. They can often be made to showanything, which is quite another matter; but if properly exhibited and compared they lead to one conclusion only; they show the truth.

In 1887 Dr. Edgar M. Crookshank, who at that time was professor of pathology and bacteriology at King’s College, was asked by the government to investigate an outbreak of cowpox in Wiltshire. Sir James Paget drew his attention to Creighton’s work, evidently hoping that Crookshank would refute it, but the results of his laborious investigations are contained in two large volumes entitled "The History and Pathology of Vaccination", in which he says that the credit given to vaccination belongs to sanitation and isolation and that nothing would more redound to the credit of the medical profession than to give up their faith in vaccination.

In 1889, in response to widespread public resistance, Parliament appointed a Royal Commission to draft recommendations to reform the system. The Commission published its conclusions in 1896.

It suggested allowing conscientious objection, an exemption which passed into law in 1898. In the early 20th century, <200,000 exemptions were granted annually, representing ≈25% of all births

In the 1893 smallpox outbreak, the well-vaccinated district of Mold in Flintshire, England, had a death rate about 32 times higher than Leicester.

Leicester, with a population under ten years of age practically unvaccinated, had a small-pox death-rate of 144 per million; whereas Mold, with all the births vaccinated for eighteen years previous to the epidemic, had one of 3,614 per million.

An Act of 1907 required declaration of objection to vaccination before the baby was 4 months old which greatly increased those granted an exemption

By 1925 smallpox had shrunk to the vanishing point. In 1872 when 85% of infants were vaccinated there were 19,000 small pox deaths. By 1925 with improved sanitation and less than 50% of children vaccinated there were only 6 deaths

In answer to a 1925 article headed "Vaccination Wins Again" in the Detroit Saturday Night Press, a prominent activist Miss Lily Loat points out :

(1) That the disease which is being diagnosed as smallpox in unvaccinated persons in England is hardly distinguishable from chickenpox, the absence or presence of vaccination marks being the fact that definitely decides the diagnosis.

This has been admitted by English medical officers of health and the Ministry of Health has twice stated in answer to questions in Parliament that vaccination is one factor in the diagnosis of these cases.

(2) That as in those districts where this very mild disease is running the vast majority of the children are unvaccinated, it would be difficult for the disease to find a child who had been vaccinated in infancy to attack.

(3) That those cases which, though vaccinated immediately after being in contact with this alleged smallpox, subsequently contract it, are all classified as unvaccinated (seems true today with COVID vax)

In 1948 Dr. Millard stated:

…in Leicester during the 62 years since infant vaccination was abandoned there have been only 53 deaths from smallpox, and in the past 40 years only two deaths. Moreover, the experience in Leicester is confirmed, and strongly confirmed, by that of the whole country.

Vaccination has been steadily declining ever since the “conscience clause” (exemption) was introduced, until now nearly two-thirds of the children born are not vaccinated.

Yet smallpox mortality has also declined until now quite negligible. In the fourteen years 1933-1946 there were only 28 deaths in a population of some 40 million, and among those 28 there was not a single death of an infant under 1 year of age.

Dr. Millard, who had been the minister of health in Leicester from 1901 to 1935, explained

“smallpox mortality continued to decrease even after vaccination was decreasing also, and this had now gone on for 60 years. Obviously there must have been other causes at work which brought about the dramatic fall in smallpox mortality since the beginning of the nineteenth century, and to the extent vaccination has for so many years been receiving more credit—perhaps much more—than it was entitled to.”

The WHO was forced to implement a version of the Leicester Method in the latter stages of their smallpox campaigns, when it became plain to them that vaccination didn’t reliably protect.

Yugoslavia experienced a smallpox epidemic beginning in February 1972. The index case was a recently vaccinated Yugoslavian haji pilgrim who picked up the disease while traveling through Iraq. He had been vaccinated in December 1971 at a public health clinic.

By the time the epidemic was controlled in April of 1972, there were 175 cases and 35 deaths. Of note was that the older portion of the population was highly vaccinated, and the third wave of cases was almost all in people who were previously vaccinated.

The WHO’s own report states:

In the age group 20 and over, 92 patients had previously been vaccinated while 21 were unvaccinated. The relatively large number of previously vaccinated cases among those over seven years of age indicates a substantial decrease in post-vaccinal immunity following primary vaccination, as well as a lack of successful revaccination when they were seven and 14 years old.

Even though they knew that vaccination was ineffective, the Yugoslavian Federal Epidemiologic Commission went ahead and vaccinated 18 million citizens. Vaccination had to continue through the end of April because so many of the vaccinations were considered unsuccessful and had to be repeated.

The Leicester Method was also carried out, and all cases were quickly quarantined. Contacts were placed in special quarantine facilities (e.g. in the Djakovica hospital and in a motel near Belgrade). There were also quarantine facilities set up in individual houses, as well as in whole villiages, as was the case with Danjane and Ratkovac and some other villiages.

The epidemic was rapidly extinguished. Vaccination, although known to be ineffective, had to be implemented if the history of vaccine success was to be upheld. But what really stopped the epidemic was use of the Leicester Method (Note-Small pox is much easier to contain than respiratory viruses which are airborne and are able to spread when patients are pre-symptomatic and are silent spreaders, unlike Small Pox which spreads via close contact when patients are noticeably symptomatic)

Routine smallpox vaccination ended in 1971. British parents had avoided it for years, with uptake much lower than for other diseases and the legacy of the Victorian Vaccination Acts looming large over the entire programme.

The 33rd World Health Assemblydeclared the world free of Small Pox on May 8, 1980.

Do you still think it was the Vaccine that deserves credit?