Recent COVID Papers of Interest

New batch of Interesting COVID Papers I have read since the last batch

Duration of immune protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection in Qatar

Effectiveness of pre-Omicron primary infection against pre-Omicron reinfection was 85.5% (95% CI: 84.8-86.2%). Effectiveness peaked at 90.5% (95% CI: 88.4-92.3%) in the 7th month after the primary infection, but waned to ∼70% by the 16th month. Extrapolating this waning trend using a Gompertz curve suggested an effectiveness of 50% in the 22nd month and <10% by the 32nd month. Effectiveness of pre-Omicron primary infection against Omicron reinfection was 38.1% (95% CI: 36.3-39.8%) and declined with time since primary infection. A Gompertz curve suggested an effectiveness of <10% by the 15th month.

Effectiveness of primary infection against severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19 reinfection was 97.3% (95% CI: 94.9- 98.6%), irrespective of the variant of primary infection or reinfection, and with no evidence for waning. Similar results were found in sub-group analyses for those ≥50 years of age.

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.06.22277306v1

Duration of Shedding of Culturable Virus in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (BA.1) Infection

A new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) has demonstrated that people who are triple-vaccinated (boosted) against COVID recover significantly more slowly from COVID infection and remain contagious for longer than people who are not vaccinated at all.

The study did not deal with the severity of illness with or without a vaccine.

Researchers swabbed infected people and cultured the swabs, repeating the process for over two weeks until viral replication was not observed.

At five days post-infection, less than 25 percent of unvaccinated people were still contagious, whereas around 70 percent of boosted people were still carrying viable virus particles. For those partially vaccinated, around 50 percent were still contagious at this point.

Even more strikingly, at ten days post-infection, one-third of boosted people (31 percent) were found to still be carrying live, culturable virus. By contrast, just six percent of unvaccinated people were still contagious at day 10.

In other words, people who have received a booster shot are five times more likely still to be contagious at ten days post-infection than are unvaccinated people

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2202092?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Upper airway gene expression shows a more robust adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in children

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-31600-0.pdf

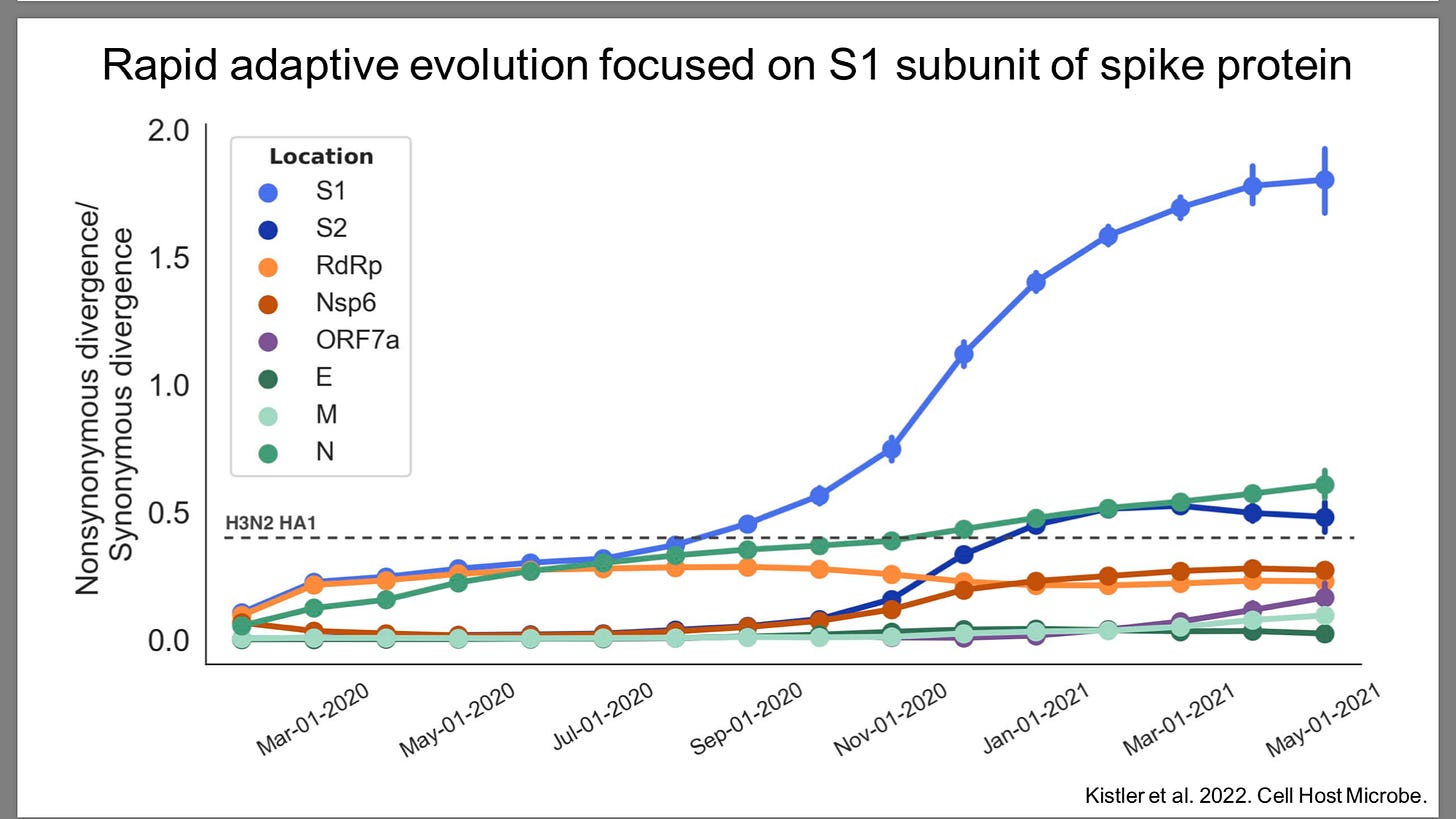

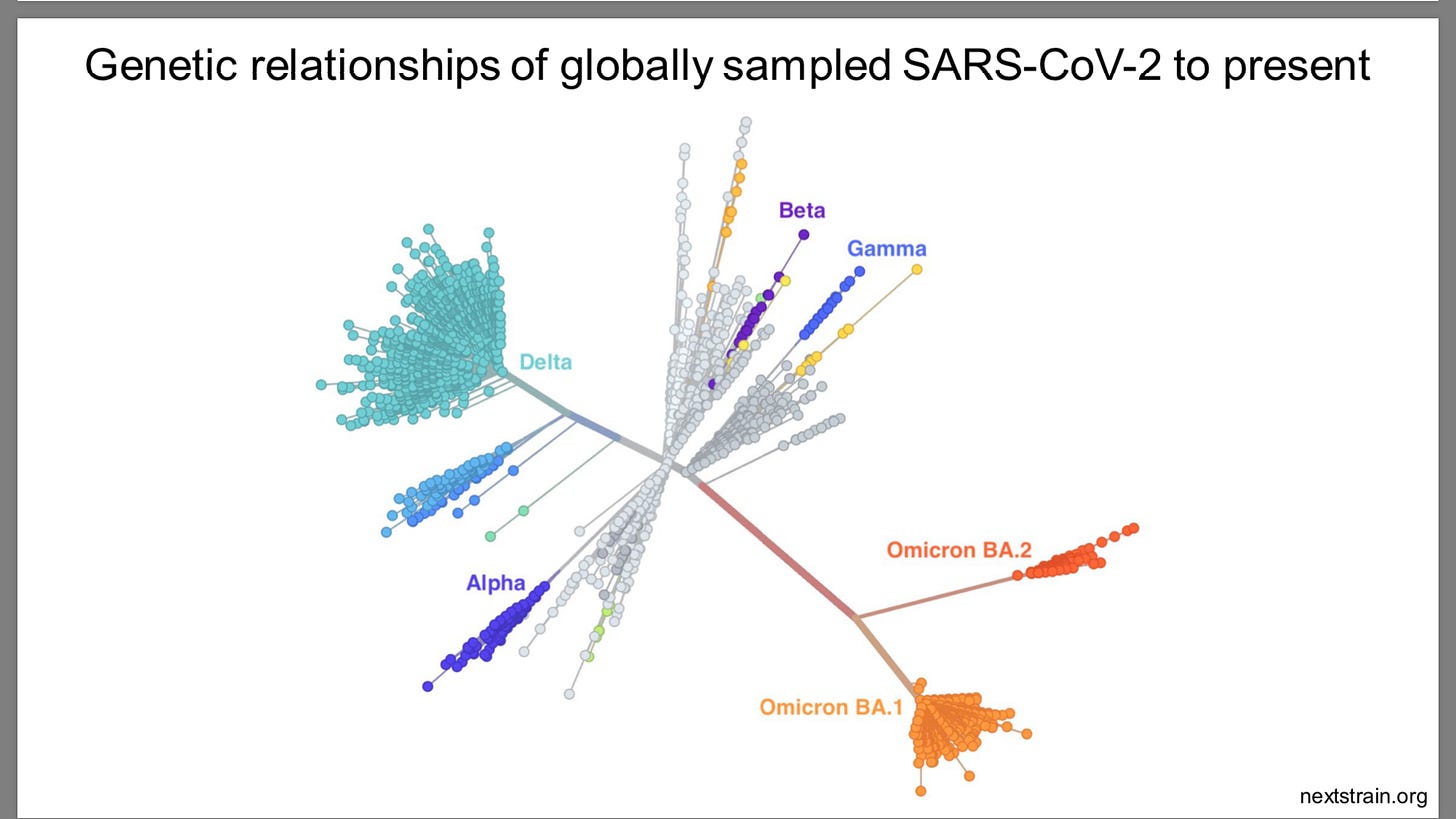

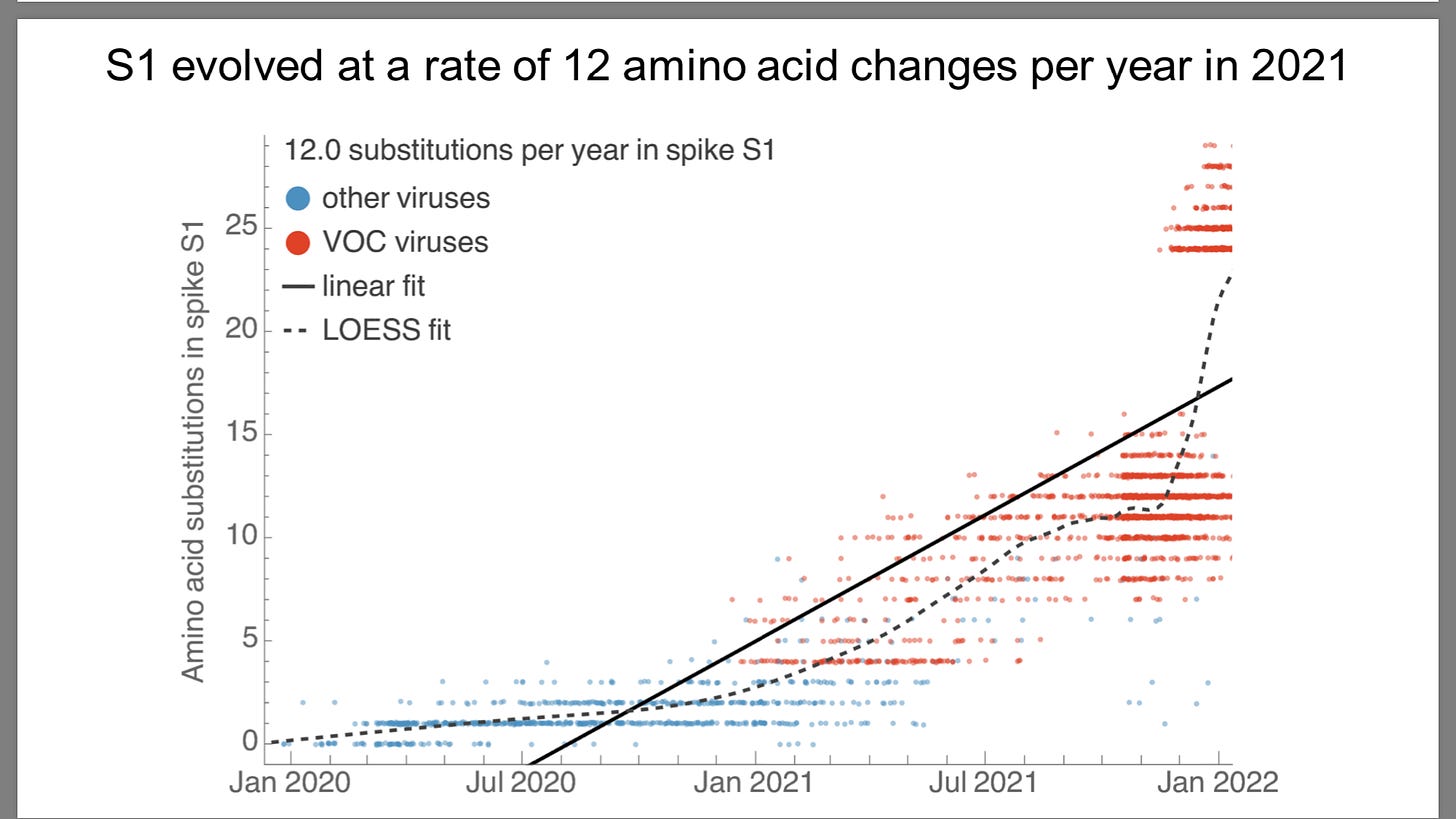

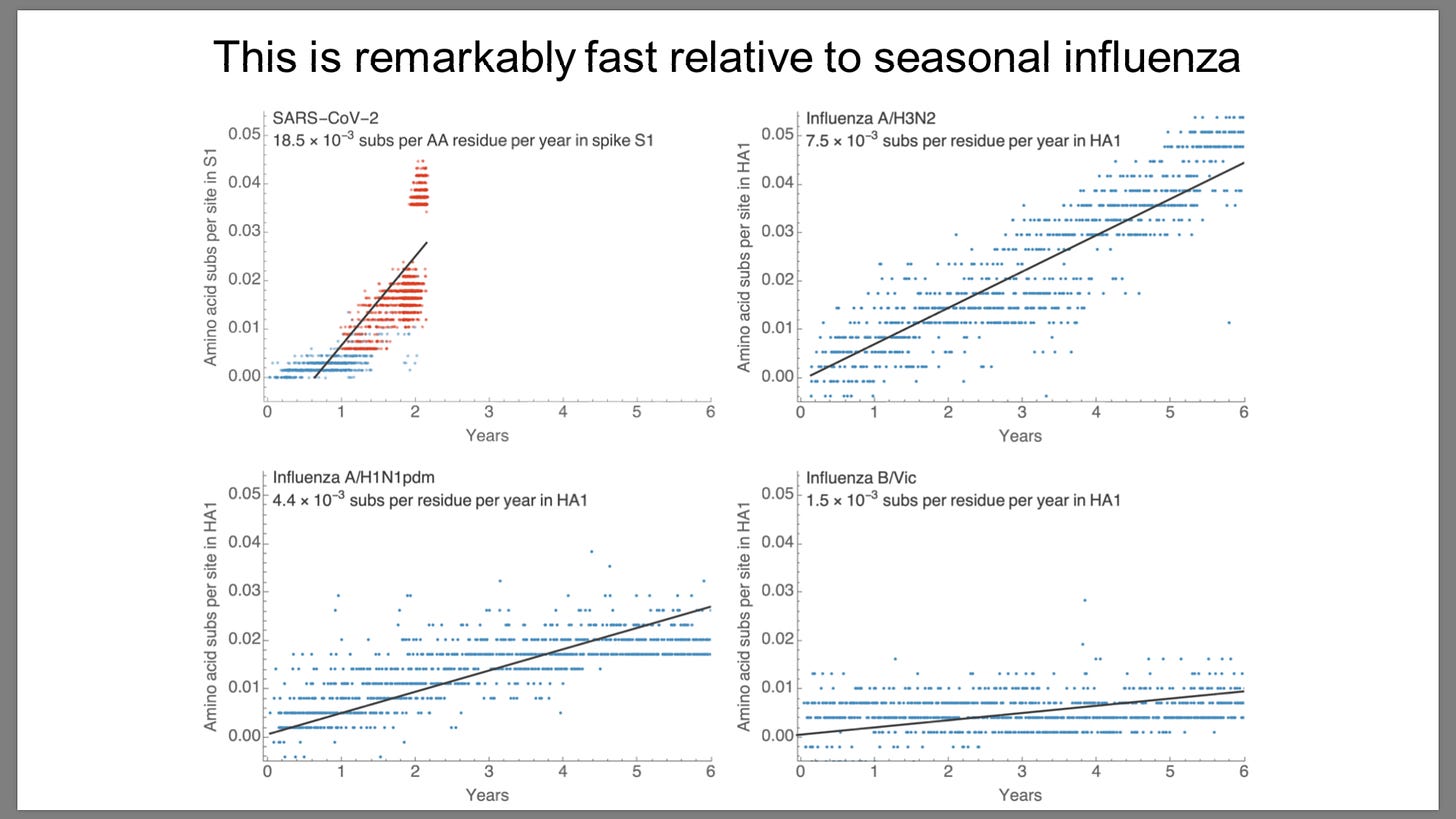

Sars-Cov-2 mutates 2-10 times faster than influenza

https://www.fda.gov/media/157471/download

Intracellular Reverse Transcription of Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine BNT162b2 In Vitro in Human Liver Cell Line

mRNA is reversed transcribed to DNA. However, they state

“At this stage, we do not know if DNA reverse transcribed from BNT162b2 is integrated into the cell genome. “

https://www.mdpi.com/1467-3045/44/3/73/htm

The Incidence of Myocarditis and Pericarditis in Post COVID-19 Unvaccinated Patients—A Large Population-Based Study

Conclusion: Our data suggest that there is no increase in the incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in COVID-19 recovered patients compared to uninfected matched controls. Further longer-term studies will be needed to estimate the incidence of pericarditis and myocarditis in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/8/2219/htm?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Increasing SARS-CoV2 cases, hospitalizations and deaths among the vaccinated elderly populations during the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant surge in UK.

When comparing the period of February 28-May 1, 2022 with the prior 12-weeks, we observed a significant increase in the case fatality rate (0.19% vs 0.41%; RR 2.11[ 2.06-2.16], p<0.001) and odds of hospitalization (1.58% vs 3.72%; RR 2.36[2.34-2.38]; p<0.001).

During the same period a significant increase in cases (23.7% vs 40.3%; RR1.70 [1.70-1.71]; p<0.001) among 50 years of age and hospitalizations (39.3% vs 50.3%;RR1.28 [1.27-1.30]; p<0.001) and deaths (67.89% vs 80.07%;RR1.18 [1.16-1.20]; p<0.001) among 75 years of age was observed.

The vaccine effectiveness (VE) for the third dose was in negative since December 20, 2021, with a significantly increased proportion of SARS-CoV2 cases hospitalizations and deaths among the vaccinated; and a decreased proportion of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among the unvaccinated.

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.28.22276926v1.full.pdf

COVID-19 Deaths in Children and Young People: Active Prospective National Surveillance, March 2020 to December 2021, England

Findings: There were 185 deaths during the 22-month follow-up and 81 (43.8%) were due to COVID-19. Compared to non-COVID-19 deaths in CYP with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, death due to COVID-19 was independently associated with older age (aOR 1.06 95%CI 1.01-1.11, p=0.02) and underlying comorbidities (aOR 2.52 95%CI 1.27-5.01, p=0.008), with a shorter interval between SARS-CoV-2 testing and death.

Half the COVID-19 deaths (41/81, 51%) occurred within 7 days of confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and 91% (74/81) within 30 days.

Of the COVID-19 deaths, 61 (75.3%) had an underlying condition, especially severe neurodisability (n=27) and immunocompromising conditions (n=12).

Over the 22-month surveillance period, SARS-CoV-2 was responsible for 1.2% (81/6,790) of all deaths, with an infection fatality rate of 0.70/100,000 SARS-CoV-2 infections in CYP aged <20 years estimated through real-time, nowcasting modelling and a mortality rate of 0.61/100,000.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4125501

Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines and measures to prevent them

Recently, The Lancet published a study on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and the waning of immunity with time [1]. The study showed that immune function among vaccinated individuals 8 months after the administration of two doses of COVID-19 vaccine was lower than that among unvaccinated individuals. These findings were more pronounced in older adults and individuals with pre-existing conditions.

The decrease in immunity is caused by several factors. First, N1-methylpseudouridine is used as a substitute for uracil in the genetic code. The modified protein may induce the activation of regulatory T cells, resulting in decreased cellular immunity [4]. Thereby, the spike proteins do not immediately decay following the administration of mRNA vaccines. The spike proteins present on exosomes circulate throughout the body for more than 4 months [5]. In addition, in vivo studies have shown that lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) accumulate in the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and ovaries [6], and that LNP-encapsulated mRNA is highly inflammatory [7]. Newly generated antibodies of the spike protein damage the cells and tissues that are primed to produce spike proteins [8], and vascular endothelial cells are damaged by spike proteins in the bloodstream [9]; this may damage the immune system organs such as the adrenal gland.

Additionally, antibody-dependent enhancement may occur, wherein infection-enhancing antibodies attenuate the effect of neutralizing antibodies in preventing infection [10]. The original antigenic sin [11], that is, the residual immune memory of the Wuhan-type vaccine may prevent the vaccine from being sufficiently effective against variant strains. These mechanisms may also be involved in the exacerbation of COVID-19.

https://virologyj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12985-022-01831-0

Serious Adverse Events of Special Interest Following mRNA Vaccination in Randomized Trials

Results: Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines were associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events of special interest, with an absolute risk increase of 10.1 and 15.1 per 10,000 vaccinated over placebo baselines of 17.6 and 42.2 (95% CI -0.4 to 20.6 and -3.6 to 33.8), respectively.

The excess risk of serious adverse events of special interest surpassed the risk reduction for COVID-19 hospitalization relative to the placebo group in both Pfizer and Moderna trials (2.3 and 6.4 per 10,000 participants, respectively).

[Note: Unfortunately while the study exposed a flaw in the clinical trial and the approval rationale its of little use in providing a real world risk rationale . The main reason is the trial participants were far healthier than the population at large (just look at all cause mortality during the trial-very low) and thus far less susceptible to COVID. Furthermore, the trial was conducted during a period of apparently relatively low COVID prevalence ( very low infection rate in placebo group ~1%). Of course thats hard to prove since unlike in the real world testing was not done on asymptomatic persons.

More proof the clinical trial was garbage and risk benefit assessment was non-existent, so thats good.]

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4125239

Virological characteristics of the novel SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants including BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5

Cell culture experiments showed that BA.2.12.1 and BA.4/5 replicate more efficiently in human alveolar epithelial cells than BA.2, and particularly, BA.4/5 is more fusogenic than BA.2.

Furthermore, infection experiments using hamsters indicated that BA.4/5 is more pathogenic than BA.2. Altogether, our multiscale investigations suggest that the

96 risk of L452R/M/Q-bearing BA.2-related Omicron variants, particularly BA.4 and BA.5, to global health is potentially greater than that of original BA.2.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.26.493539v1.full.pdf

BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection

Infections with the "old" omicron subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 provide little protection against the SARS-CoV-2 subvariant BA.5 causing a “summer wave” of cases in Germany

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(22)00422-4/fulltext

Together, our results indicate that Omicron may evolve mutations to evade the humoral immunity elicited by BA.1 infection, suggesting that BA.1-derived vaccine boosters may not achieve broad-spectrum protection against new Omicron variants

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04980-y_reference.pdf

Effects of Previous Infection and Vaccination on Symptomatic Omicron Infections

Previous infection alone, BNT162b2 vaccination alone, and hybrid immunity all showed strong effectiveness (>70%) against severe, critical, or fatal Covid-19 due to BA.2 infection. Similar results were observed in analyses of effectiveness against BA.1 infection and of vaccination with mRNA-1273.

CONCLUSIONS

No discernable differences in protection against symptomatic BA.1 and BA.2 infection were seen with previous infection, vaccination, and hybrid immunity. Vaccination enhanced protection among persons who had had a previous infection. Hybrid immunity resulting from previous infection and recent booster vaccination conferred the strongest protection

Over six months after getting two doses of the Pfizer vaccine, immunity against any Omicron infection dropped to -3.4 percent.

But for two doses of the Moderna vaccine, immunity against any Omicron infection dropped to -10.3 percent after more than six months since the last injection.

This means unless you continue to get boosted you will be more likely to get COVID than if unvaxxed

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2203965?query=featured_home

Analysis of NEJM STUDY ABOVE

This study was huge in scale, sifting through data collected from over 100,000 people infected by the Omicron variant. It lends credibility to the statistical significance of the findings, which are absolutely startling. Here are the key points:

Those who have been "fully vaccinated" with two shots from Moderna or Pfizer are more likely to contract Covid-19 than those who have not been vaccinated at all

Booster shots offer protection approximately equal to natural immunity, but the benefits wane after 2-5 months

Natural immunity lasts for at least 300-days, which is the length of the study; it likely lasts much longer”

“The authors of the study found that those who had a prior infection but no vaccination had a 46.1 and 50 percent immunity against the two subvariants of the Omicron variant, even at an interval of more than 300 days since the previous infection.

However, individuals who received two doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine but had no previous infection, were found with negative immunity against both BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron subvariants, indicating an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 than an average person.

Over six months after getting two doses of the Pfizer vaccine, immunity against any Omicron infection dropped to -3.4 percent. But for two doses of the Moderna vaccine, immunity against any Omicron infection dropped to -10.3 percent after more than six months since the last injection.

Though the authors reported that three doses of the Pfizer vaccine increased immunity to over 50 percent, this was measured just over 40 days after the third vaccination, which is a very short interval. In comparison, natural immunity persisted at around 50 percent when measured over 300 days after the previous infection, while immunity levels fell to negative figures 270 days after the second dose of vaccine.

These figures indicate a risk of waning immunity for the third vaccine dose as time progresses.

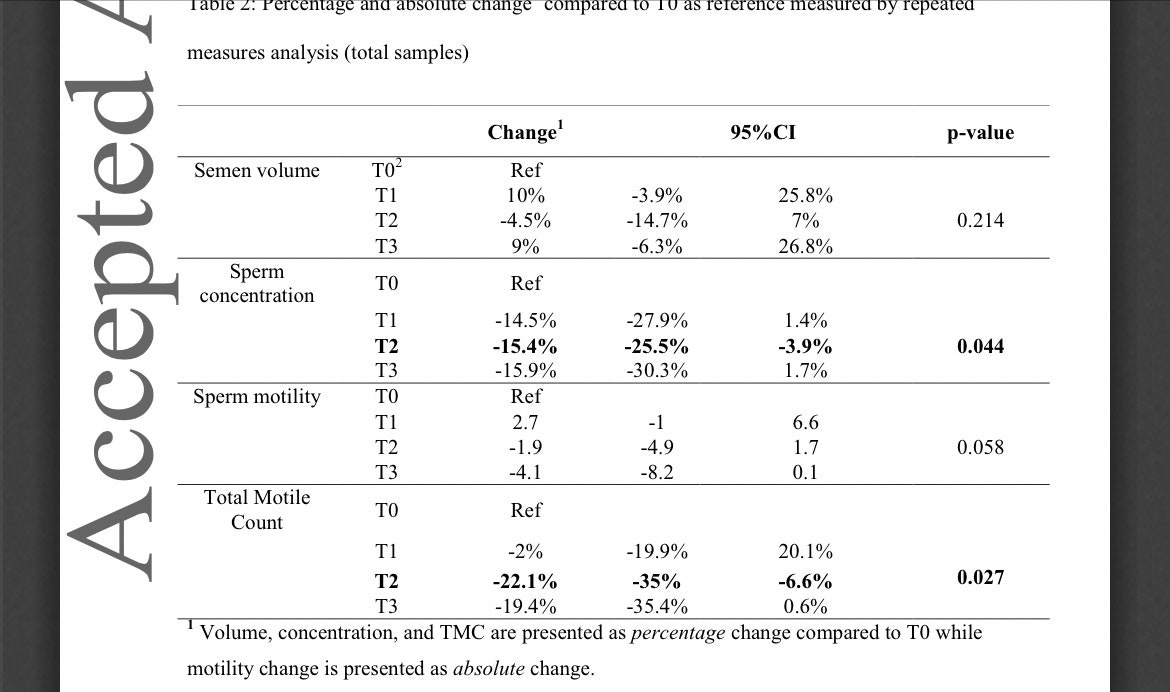

Covid-19 vaccination BNT162b2 temporarily impairs semen concentration and total motile count among semen donors

Below is the crucial chart, which shows that “total motile count” - the number of sperm in the ejaculated semen - plunged 22 percent three to five months after the second shot (T2) and barely recovered during the final count (T3), when it was still 19 percent below the pre-shot level.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/andr.13209

Fatal COVID-19 outcomes are associated with an antibody response targeting epitopes shared with endemic coronaviruses

Persistent circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike is associated with post-acute COVID-19 sequelae

The magnitude of antibody responses to the SARS-CoV-2 full-length spike protein, its domains and subunits, and the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid also correlated strongly with responses to the endemic beta-coronavirus

90 spike proteins in individuals admitted to intensive care units (ICU) with fatal COVID-19 outcomes, but not in individuals with non-fatal outcomes. This correlation was found to be due to the antibody response directed at the S2 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which has the highest degree of conservation between the beta-coronavirus spike proteins. Intriguingly, antibody responses to the less cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid were not significantly different in individuals who were admitted to ICU

Individuals with fatal COVID-19 outcomes make lower antibody responses to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein but not the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid

Furthermore, we found that individuals admitted to ICU with fatal outcomes had antibody responses to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, NTD, full-length spike and nucleocapsid that correlated strongly with the SARS-CoV-2 S2 antibody responses (Figure 2B). These correlations were absent in individuals in the ICU non-fatal COVID-19 outcomes group, and are denoted by a black cross.

https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/156372#.Yo5OEYhfDy0.twitter

Estimates vary as to the prevalence of PASC,but the World Health Organization (WHO) reports around one quarter of individuals with COVID-19 continue to experience symptoms 4-5 weeks after a positive test and approximately one in 10 have continuing symptoms after 12 weeks.

We analyzed plasma samples from a cohort of 63 individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, 37 of whom were diagnosed with PASC. For most of the PASC patients (n = 31), blood samples were collected two or more times up to 12 months after their first positive result with either a nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR test or an anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody test. Blood was also collected from individuals who suffered from COVID-19, but were not diagnosed with PASC, up to five months post-diagnosis. The majority of PASC patients were female (n = 30), consistent with other studies that found women are predominantly affected by persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

We were able to detect either S1, spike or N in approximately 65% of the patients diagnosed with PASC at any given time point, several months after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Out of all three antigens measured, we detected spike most often in 60% of the PASC patients, whereas we did not detect spike at all in the COVID-19 patients.

S1 was detected to a lesser degree in about one-fifth of the PASC patients and N was detected in a single patient at multiple time points.

In line with our previous work,we detected S1 and N in COVID-19 patients, often those hospitalized with severe disease and within the first week post-diagnosis but we did not detect the full spike protein in any of these patients.

In only a few cases, the presence of S1 or spike may be correlated with vaccination, however according to our previous findings, S1 is only detected within the first two weeks after the first dose and spike is rarely detected.

[the study does not show vaccination status or times of most recent vaccination]

Most significantly, we observe patterns of sustained full spike antigen levels over the course of several months in many [PASC] patients.

The minority of our PASC cohort was hospitalized (n=2), suggesting that our findings relate to SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than effects that arise after severe illness and hospitalization.

The presence of circulating spike supports the hypothesis that a reservoir of active virus persists in the body.

[ Or Vaccination-unfortunately they don’t provide Vaccination details of their PASC patients]

Another preliminary study found SARS-CoV-2 RNA in multiple anatomic sites up to seven months after symptom onset, corroborating viral antigen persistence.

[or Vaccine mRNA]

Post-mortem tissue analysis revealed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and viral specific protein expression not only in respiratory tissues, but also in cardiovascular, lymphoid, gastrointestinal, peripheral nervous, and brain tissues in the majority of individuals analyzed (n = 44).

Furthermore, in our previous study, a reservoir of replicating SARS-CoV-2 was found to occur in the gastrointestinal tract of children who develop multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C). In that study, we detected elevated levels of circulating spike weeks after initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, due to leakage from the gut into the blood stream.

In another study, analysis of the gut microbiome up to six months after SARS-CoV-2 infection revealed alterations in the gut microbiome composition that correlated with PASC, suggesting that certain conditions or predispositions may foster the persistence of replicating viral reservoirs.

If viral reservoirs persist in the body of PASC patients, then why do we not also detect circulating N in a larger proportion of patients? It is possible that N is preferentially hydrolyzed, whereas spike may be more efficiently transported into the bloodstream, evading degradation.

[and maybe the spike is from vaccination. Too bad we dint have studies showing how fast spike is degraded after vaccination or infection]

spike alone was shown to disrupt signaling pathways and induce dysfunction in pericytes, vascular endothelial cells, and the blood brain barrier.

[nice of you to admit that]

Alternatively, PASC may manifest as cellular exhaustion or the induction of refractory inflammatory response – but with persistent tissue localized dysfunction.

[cellular exhaustion from repeated vaccination/infection seems possible as well ]

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.14.22276401v1.full.pdf

Persistent circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike is associated with post-acute COVID-19 sequelae

This study was referenced in the above PASC study. Done by heavy weights in NIH, NIAID, NCI and published in Dec 2021

.COVID-19 is known to cause multi-organ dysfunction1-3 in acute infection, with prolonged symptoms experienced by some patients, termed Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC)

We performed complete autopsies on 44 patients with COVID-19 to map and quantify SARS-CoV-2 distribution, replication, and cell-type specificity across the human body, including brain,from acute infection through over seven months following symptom onset.

We show that SARS-CoV-2 is widely distributed, even among patients who died with asymptomatic to

mild COVID-19, and that virus replication is present in multiple pulmonary and extrapulmonary tissues early in infection.

Further, we detected persistent SARS-CoV-2 RNA in multiple anatomic sites, including regions throughout the brain, for up to 230 days following symptom onset.

Despite extensive distribution of SARS-CoV-2 in the body, we observed a paucity of inflammation or direct viral cytopathology outside of the lungs.

Our data prove that SARS-CoV-2 causes systemic infection and can persist in the body for months.

While autopsy studies of fatal COVID-19 cases support the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect multiple organs extra-pulmonary organs often lack histopathological evidence of direct virally-mediated injury or inflammation. The paradox of extra-pulmonary infection without injury or inflammation raises many pathogen- and host-related questions.

[I love paradox mysteries but I smell a rat]

These questions include, but are not limited to: What is the burden of infection within versus outside of the respiratory tract?

What cell types are infected across extra-pulmonary tissues, and do they support SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication?

In the absence of cellular injury and inflammation in extra-pulmonary tissues, does SARS-CoV-2 persist, and if so, over what interval? Does SARS-CoV-2 evolve as it spreads to and persists in different anatomical compartments?

[the virus is hiding in our organs and replicating silently while evolving to become bigger and badder. Oh my. Mommy, I am scared]

we performed extensive autopsies on a diverse population of 44 individuals who died from or with COVID-19 up to 230 days following initial symptom onset.

Patients presented to the hospital a mean of 9.4 days following symptom onset and were hospitalized a mean of 26.4 days. Overall,the mean interval from symptom onset to death was 35.2 days and the mean postmortem interval was 26.2 hours.

81.8% of patients required intubation with invasive mechanical ventilation,

22.7% received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support, and 40.9% required renal replacement therapy. Vasopressors, systemic steroids, systemic anticoagulation, and antibiotics were commonly administered

[These were real sick puppies]

We detected sgRNA in at least one tissue in over half of cases (14/27) beyond D14, suggesting that prolonged viral replication may occur in extra-pulmonary tissues as late as D99. While others have questioned if extrapulmonary viral presence is due to either residual blood within the tissue or cross-contamination from the lungs during tissue procurement, our data rule out both theories.

Only 12 cases had detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a perimortem plasma sample, and of these only two early cases also had SARS-CoV-2

sgRNA in the plasma, which occurred at Ct levels higher than nearly all of their tissues with sgRNA.

Therefore, residual blood contamination cannot account for RNA levels within tissues.

Furthermore, blood contamination would not account for the SARS-CoV-2 sgRNA or virus isolated from tissues.

Contamination of additional tissues during procurement, is likewise ruled out by ISH demonstrating widespread SARS-CoV-2 cellular tropism across the sampled organs, by IHC detecting viral protein in the brain, and by several cases of virus genetic compartmentalization in which spike variant sequences that were abundant in extrapulmonary tissues were rare or undetected in lung samples.

Although our cohort is primarily made up of severe cases of COVID-19, two early cases had mild respiratory symptoms (P28; fatal pulmonary embolism occurred at home) or no symptoms (P36; diagnosed upon hospitalization for ultimately fatal complications of a comorbidity), yet still had SARS-CoV-2 RNA widely detected across the body, including brain, with detection of sgRNA in multiple compartments.

Our findings, therefore, suggest viremia leading to body-wide dissemination, including across the blood-brain barrier, and viral replication can occur early in COVID-19, even in asymptomatic or mild cases

[yeah, in really sick puppies dying from other reasons]

While the respiratory tract was the most common location in which SARS-CoV-2 RNA tends to linger, ≥50% of late cases also had persistence in the myocardium, thoracic cavity lymph nodes, tongue, peripheral nerves, ocular tissue, and in all sampled areas of the brain, except the dura mater.

Interestingly, despite having much lower levels of SARS-CoV-2 in early cases compared to respiratory tissues, we found similar levels between pulmonary and the extrapulmonary tissue categories in late cases.

This less efficient viral clearance in extrapulmonary tissues is perhaps related to a less robust innate and adaptive immune response outside the respiratory tract.

We detected sgRNA in tissue of over 60% of the cohort. While less definitive than viral culture , multiple studies have shown that sgRNA levels correlate with acute infection and can be detected in respiratory samples of immunocompromised patients experiencing prolonged infection

These data coupled with ISH suggest that SARS-CoV-2 can replicate within tissue for over 3 months after infection in some individuals, with RNA failing to clear from multiple compartments for up to D230.

[This sick puppy was on immunosuppressive drugs due to a liver transplant]

This persistence of viral RNA and sgRNA may represent infection with defective virus, which has been described in persistent infection with measles virus –another single-strand enveloped RNA virus—in cases of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

The mechanisms contributing to PASC are still being investigated; however, ongoing systemic and local inflammatory responses have been proposed to play a role5. Our data provide evidence for delayed viral clearance, but do not support significant inflammation outside of the respiratory tract even among patients who died months after symptom onset.

Understanding the mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 persists and the cellular and subcellular host responses to viral persistence promises to improve the understanding and clinical management of PASC.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6b67/929619b7542218923cca83420fa606cb41b1.pdf

Immune boosting by B.1.1.529 (Omicron) depends on previous SARS-CoV-2 exposure

Overall, more than half (27/50; 54%) made no T cell response against S1 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) protein, irrespective of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection history, compared to 8% (4/50) that made no T cell response against ancestral Wuhan Hu-1 S1 protein (p < 0.0001, Chi-square test) .

The fold-reduction in geometric mean of T cell response (SFC) against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 compared to ancestral Wuhan Hu-1 S1 protein was

17.3-fold for infection-naïve HCW ,

7.7-fold for previously Wuhan Hu-1 infected

8.5-fold for previously B.1.1.7 (Alpha) infected

and 19-fold for previously B.1.617.2 (Delta) infected

42% (21/50) of HCW make no T cell response at all against the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) VOC mutant pool

Overall, our findings in triple-vaccinated HCW with different previous SARS-CoV-2 infection histories indicated that T cell cross-recognition of B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 antigen and peptide pool was significantly reduced.

T cell and nAb responses against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) were discordant and most (20/27, 74%) HCW with no T cell response against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 made cross-reactive nAb against B.1.1.529 at an IC50 >195 .

infection during the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) wave produced potent cross-reactive antibody immunity against all VOC, but less so against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) itself.(imprinting)

Importantly, triple-vaccinated, infection-naïve HCW that were not infected during the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) wave made no nAb IC50 response against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) 14 weeks after the third vaccine dose indicating rapid waning of the nAb IC50 from a mean value of 1400 at 2-3w falling to 0 at 14w after the third dose

Thus, B.1.1.529 (Omicron) infection can boost binding and nAb responses against itselfand other VOC in triple-vaccinated previously uninfected infection naïve HCW, but not in the context of immune imprinting following prior Wuhan Hu-1 infection.

Immune imprinting by prior Wuhan Hu-1 infection completely abrogated any enhanced nAb responses against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) and other VOC

B.1.1.529 (Omicron) infection resulted in enhanced, cross-reactive Ab responses against all VOC tested in the three-dose vaccinated infection-naïve HCW, but not those with previous Wuhan Hu-1 infection, and less so against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) itself .

Fourteen weeks after the third dose (9/10, 90%) of triple-vaccinated, previously infection-naïve HCW showed no cross-reactive T cell immunity against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 protein .

Importantly, none (0/6) of HCW with a previous history of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Wuhan Hu-1 wave responded to B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 protein . This suggests that, in this context, B.1.1.529 (Omicron) infection was unable to boost T cell immunity against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) itself; immune imprinting from prior Wuhan Hu-1 infection resulted in absence of a T cell response against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) S1 protein.

Fourteen weeks after the third vaccine dose previously infection-naïve HCW infected during the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) wave showed increased S1 RBD B.1.1.529 (Omicron) binding responses, but prior Wuhan Hu-1 infected HCW did not, indicating that prior Wuhan Hu-1 infected individuals were immune imprinted to not boost antibody binding responses against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) despite having been infected by B.1.1.529 (Omicron) itself

mRNA vaccination carrying the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) spike sequence (Omicron third-dose after ancestral sequence prime/boosting) offers no protective advantage