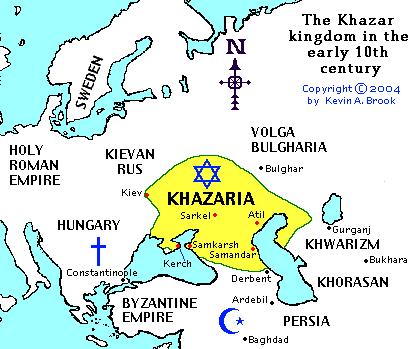

Khazaria

Khazaria

This is a work in progress. A place to drop my research notes so I wont be distributing it by email

The 2012 genetic discoveries by Dr. Eran Elhaik of the prestigious Johns Hopkins Medical University, show that many Jews originated in Khazaria.

https://www.haaretz.com/2012-12-28/ty-article/.premium/the-jewish-peoples-ultimate-treasure-hunt/0000017f-f70a-d47e-a37f-ff3e820d0000

The South Eastern parts of Ukraine are historically part of what used to be known as Greater Khazaria, a great Jewish State long before Israel

Most of this area, should Putins Army have its way, is or will soon be under Russias control. Some Israelis call it the New Khazaria

What do you know about Khazaria?

Before we begin we should know a little bit about how Judaism spread before the fall of the 2nd Temple and the rise of Christianity

From Shlomo Sand

Conversion is mentioned as one reason for the vast presence of

Jewish believers throughout the ancient world before the fall of the Second

Temple. But this decisive factor was sidelined, as we have seen, while the more

dramatic players of Jewish history dominated the field: expulsion, displace- ment, emigration and natural increase.

These gave a more appropriate ethnic quality to the "dispersion of the Jewish people." Dubnow and Baron did make greater allowance for conversion, but the stronger Zionist writings played it down, and in the popular historical works—above all in the textbooks, which shape public consciousness—it all but vanished from the picture.

It is generally assumed that Judaism has never been a missionizing religion, and if some proselytes joined it, they were accepted by the Jewish people with extreme reluctance. "Proselytes are an affliction to Israel," the famous pronouncement in the Talmud, is invoked to halt any attempted discussion of the subject. When was this statement written? Did it in any way reflect the principles of the faith and the forms of Jewish experience in the long period between the Maccabee revolt in the second century BCE and the Bar Kokhba uprising in the second century CE? That was the historical period in which the number of Jewish believers in the Mediterranean cultural world reached a level that would again be matched only in the early modern age.

The period between Ezra in the fifth century BCE and the revolt of the Maccabees in the second was a kind of dark age in the history of the Jews. Zionist historians rely on the biblical narrative for the time leading up to that period, and on the Books of the Maccabees and the final part of Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews for the end of it. Information about that obscure period is very sparse: there are the few archaeological finds;

The Judean society must have been quite small then, and when the inquisitive Herodotus passed through the country in the 440s BCE he missed it altogether.

What we do know is that, while the abundant biblical texts during this Persian period promoted the tribal principle of an exclusive "sacred seed," other authors wrote works that ran counter to the hegemonic discourse, and some of those works entered the canon.

The Second Isaiah, the Book of Ruth, the Book of Jonah and the apocryphal Book of Judith all call for Judaism to accept gentiles, and even for the whole world to adopt the "religion of Moses." Some of the authors of the Book of Isaiah proposed a universalist telos for Judaic monotheism:

And it shall come to pass in the last days that the mountain of the Lord's house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it. And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths (Isa. 2:2-3).

Ruth the Moabite, great-grandmother of King David, follows Boaz and marries him without any problem. Similarly, in the Book of Judith, Achior the Ammonite, influenced by Judith, converts to Judaism. Yet both of them belonged to peoples that Deuteronomy strictly prohibited: "An Ammonite or Moabite shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord; even to their tenth generation shall they not enter into the congregation of the Lord for ever" (Deut. 23:3). The creators of these proselytized characters depicted them to protest against the overweening isolationism of Ezra and Nehemiah's priests, those authorized agents of the Persian kingdom.

Every monotheism contains a potential element of mission. Unlike the tolerant polytheisms, which accept the existence of other deities, the very belief in the existence of a single god and the negation of plurality impels the believers to spread the idea of divine singularity that they have adopted. The acceptance by others of the worship of the single god proves his might and his unlimited power over the world.

It is not known when the biblical Book of Esther was composed. Some assume that it was first written in the late Persian period, and finally redacted in the Hellenistic. It is also possible that it was composed after the conquests of Alexander the Great. Toward the end of the story, after the triumph of Mordecai and Esther over Haman the Agagite in faraway Persia, it says, "And many of the people of the land became Jews; for the fear of the Jews fell upon them" (Esther 8:17).

This is the only mention in the Bible of conversion to Judaism, and this statement about mass conversions—not at the End of Days but in the present—indicates the strengthening confidence of the young Jewish mono-theism. It may also hint at the source of the great increase in the number of Jewish believers in that period.

A 1965 doctoral thesis by Uriel Rapaport—unfortunately not published, though its author became a well-known historian of the Second Temple period—deviated from the usual historiographic discourse and sought, without success, to draw researchers' attention to the widespread wave of conversions. Unlike all the ethnonationalist historians, Rapaport did not hesitate to conclude his brilliant thesis with this statement: "Given its great scale, the expansion of Judaism in the ancient world cannot be accounted for by natural increase, by migration from the homeland, or any other explanation that does not include outsiders joining it."

....the reason for the great Jewish increase was mass conversion. This process was driven by a policy of proselytizing and dynamic religious propaganda, which achieved decisive results amid the weakening of the pagan worldview. In this, Rapaport joined a (non-Jewish) historiographic tradition that included the great scholars of ancient history—from Ernest Renan and Julius Wellhausen to Eduard Meyer and Emil Schurer—and asserted, to use the sharp words of Theodor Mommsen, that "ancient Judaism was not exclusive at all; it was, rather, as keen to propagate itself as Christianity and Islam would be in future."

If propagating the faith began in the late Persian period, under the Hasmoneans it became the official policy It was the Hasmoneans who truly produced a large number of Jews and a great "people"

There are some indications that Judaism attracted proselytes even before the upheavals of Alexander's wars, but the explosion of conversions that led to Judaism's sudden spread probably resulted from its historic encounter with Hellenism. Just as Hellenism itself had begun to shed the vestiges of the narrow identities associated with the old city-states, so too did Ezra's isolationist religion begin to lower its exclusionary barriers.

In antiquity, the rise of a new cultural space embracing the eastern Mediterranean, and the fall of old tribal-cultic boundaries, constituted a true revolution

If the junction of Zion and Alexandria produced a universalist outlook, the junction of Judea and Babylonia gave rise to Pharisee Judaism, which would bequeath to future generations new principles of religion and worship. The rabbinical scholars, who came to be known as the sages, and their successors the tanaim and amoraim, had already begun before and after the fall of the Temple to construct the anvil on which to harden the doctrinal steel of a stubborn minority so that it could survive all hardships in bigger and mightier religious civilizations.

These groups were not genetically programmed to uphold isolation and to refuse to spread the Jewish religion. Later, in the European cultural centers, the painful dialectic between Pharisee Judaism and Pauline Christianity would intensify this tendency, especially in the Mediterranean, but the proselytizing urge did not fail for a long time.

Rabbi Chelbo's oft-quoted statement "Proselytes are as injurious to Israel as a scab" {Tractate Yevamot) certainly does not express the attitude of the Talmud toward proselytizing and proselytes. It is contradicted by the no less decisive assertion of Rabbi Eleazar, which probably preceded it, that "the Lord exiled Israel among the nations so that proselytes might swell their ranks" {Tractate Pesachim). So all the trials and tribulations of exile, and the separation from the Holy Land, were meant to increase and strengthen the congregation of Jewish believers.

Ultimately, though, it was not so much the pagan resistance as the rise of Christianity—seen as a grave heresy—that prompted stronger objections to proselytization. Christianity's final triumph in the early fourth century CE extinguished the passion for proselytizing in the main cultural centers, and perhaps also prompted the desire to erase it from Jewish history.

In Judea, Babylonia and possibly western North Africa, the diminishing number of Jews was the result not only of the mass casualties in the uprisings or of believers reverting to paganism; it was caused chiefly by people making the lateral move to Christianity. When Christianity became the state religion in the early fourth century, it halted the momentum of Judaism's expansion.

The edicts passed by the emperor Constantine I and his successors show that conversion to Judaism, though flagging, went on until the early fourth century. They also explain why Judaism began to isolate itself in the Mediterranean region. The Christianized emperor ratified the second-century edict of Antoninus Pius, forbidding the circumcision of males who were not born Jews. Jewish believers had always Judaized their slaves; this practice was now forbidden, and before long Jews were forbidden to own Christian slaves.

Constantine's son intensified the anti-Jewish campaign by forbidding the ritual immersion of proselytized women and forbade Jewish men to marry Christian women.

In the pagan world, Judaism, though persecuted, was a respectable and legitimate religion. Under repressive Christianity, it gradually became a pernicious, contemptible sect. The new church did not seek to eradicate Judaism—it wanted to preserve Judaism as an aged, humbled creature that had long since lost its admirers, and whose insignificant existence vindicated the victors.

In these circumstances, the large number of Jews around the Mediterranean inevitably declined at an accelerating rate. Zionist historians, as we shall see in the next chapter, tend to suggest that those who left Judaism in times of isolation and stress were mainly the newly converted. The "ethnic" hard core of "birth Jews"—a term often found in Zionist historiography—kept the faith and remained unalterably Jewish. There is, of course, not a shred of evidence for this völkisch interpretation. It is equally likely that the numerous families that had taken to Judaism by choice, or even their descendants in the next few generations, would have clung to it more fervently than those born to it effortlessly. Converts and their offspring famously tend to be more devoted to their chosen religion than old believers.

The Khazars

An extensive Jewish kingdom existed for over 200 years, much larger than the kingdom of the Hasmoneans in Palestine, and recorded by many more verifiable contemporary sources than the imaginary empire of David and Solomon in the bible, yet many Jews and Christians know little or nothing about it. It seems to be wilfully ignored. It was Khazaria.

The Khazars were a Turkish tribe among the Asian tribes called the Huns moving west in the fourth century AD. They were destroyed eventually by an even more irresistible movement of Asian tribes—the Mongol Horde of the thirteenth century, though the Jewish kingdom had actually fallen already, two hundred years before.

An important document, now called the Cambridge Document, was found among the old scripts disposed of in a Cairo genizah (repository of disused Jewish sacred texts) in 1912. The Hebrew document, written around the tenth century AD, states that the Jews came to Khazaria from Baghdad, Khorasan, and Greece to encourage the “men of the land” to convert to Judaism and appoint a “judge” over them whom they called the Kagan (Khakan). Khorasan, southeast of the Caspian sea, was a province of ancient Persia, and, by the coincidence too often repeated, had become the home of a myriad Jews—evidently Persian Juddin.

Sand writes that the arrival of Jewish believers from Armenia (parts of Turkey, Iran, Iraq), Mesopotamia, Khorasan (parts of Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan) and Byzantium led to the adoption of Judaism by the Khazars. All of these places with evidently substantial Jewish populations were once in the Persian empire!

Many Jews with Greek names lived in Crimea, again probably former Juddin from across the water, and proselytized Jews who had come within the Greek sphere of influence. Jews were still proselytizing in the eighth century AD in what is now the Ukraine and southern Russia, whereas Jews were prevented from proselytizing in Christian and Islamic lands.

The Khazars settled down among the indigenous Scythians between the Caspian Sea and the Crimea. Among them were Bulgars and Slavs, and Hungarians, Magyars and Alans, but the Khazars were the ruling class, led by a king called the Kagan.

They raided the Sassanid kingdom of the Persians through the Caucasus, getting as far as Mosul in Kurdistan, as we know from Persian records. This part of the ancient Achaemenid Persian empire seems to have been a center of Jewish conversion, the region which later had provided Jewish kingdoms in Armenia and Adiabene, ancient Urartu (Ararat). Eventually a treaty was settled that the Caucasus passes were to be the limit of the Khazar kingdom. The Persians fortified the frontier, the structures still being visible.

The Khazars irrigated their fields from the great rivers that crossed the steppes growing rice as a staple, and vines for wine. Fish provided much of their protein.

Otherwise the basis of the country’s power was its strategic position with respect to the east-west trade (the Silk Road) and the north-south trade of furs and slaves along the rivers. Such wealth allowed the Kagan to support a strong army, and a wealthy nobility. Though the Khazar spoken language was from the Turkic family, the sacred language in use was Hebrew (Canaanite), and their script was evidently the Aramaic scrip in which Hebrew was written. Arab writers confirm it.

The route of the Khazars into Moslem lands was the only one available—through the Caucasus mountains, through Armenia and the lands occupied by the Kurds into Mesopotamia where was Baghdad.

On one occasion (730 AD), the Khazar armies again got as far as Mosul before the Arabs repulsed them. Like the Persians, the Arabs were able to stop the Khazars at Mosul in Kurdistan. From raids like these, as well as ordinary trade, the Jews of Armenia and Persia got to know of Khazaria.

Many Jews still remained in the lands of the Persian converts originally called Juddin. But, of course, the earlier kingdom of Adiabene in this same area had become Jewish. It was the descendants of all of these converts who later went north to Khazaria and began to convert the Khazars.

The Khazars made an alliance with Byzantium against the Persians. The marriage arranged to cement the alliance led to a Byzantine emperor being called Leo the Khazar (775-780 AD). What the Byzantines gained from the alliance was a powerful state north of the Black Sea and the Caucasus that could resist the incursions of the Moslem armies that otherwise might have passed through the Caucasus and over the steppe along the northern shores of the Black Sea to attack Byzantium from the north where it was vulnerable.

Khazaria therefore helped preserve the eastern remnants of the Roman empire from the Moslems, holding back the Moslem invasion of eastern Europe for hundreds of years.

Again the Caucasus was agreed as the boundary between Khazaria and the Islamic empire, but the Kagan was forced to become a Moslem, and the Islamic religion was accepted within the kingdom. All this is historical. The Kagan was a holy leader rather than an executive, though he was highly respected as the titular head of state.

The practical head, the CEO, was called the Kagan Bey. He was the head of the army and effectively the real king. The capital city at the mouth of the Volga river, was called Itil, a city of tents and huts but with a triangular shaped fortress. It has only recently been found.

Khazaria was at first pagan, but Khazars were ready to adopt monotheism, Jewish, Christian, or Moslem. The Arab historian, Al Mas’udi, relates how the Khazar king converted in the time of the caliphate of Harun al Rashid (c 763-809 AD) when many Jews who had heard of it migrated from all the Moslem cities, and Byzantium when the Christians began forcing Jews to convert to Christianity in the tenth century. So the immigration of Jews from what had been Persia and Greece continued for over 100 years.

Rabbi Yehuda Halevi wrote a book on the Khazars called The Kuzari. An account in France about 864 AD called them the “Gazari”—oddly an alternative name for the Cathars. King Bulan was the first Kagan, but it was several generations before Kagan Obediah organized Khazaria as a proper Jewish state, inviting in Jewish sages from abroad to introduce Rabbinic orthodoxy, the Mishnah and the Talmud.

The question is, why Judaism when Christianity and Islam were much bigger and less demanding religions? That is the answer. By adopting either of the big religions, they tied Khazaria to Baghdad or to Byzantium. By choosing Judaism, they could remain independent, but they could not have remained pagan without being a constant invitation to the aggressive Moslems to conquer them and force them into Islam.

At first, it seemed the Qaraites were significant in Khazaria, especially in Crimea, but the Kagans, by bringing in orthodox Rabbinical scholars, ensured Khazaria became essentially orthodox. Qaraism might have been a relic of mainstream Judaism before the Rabbis changed the religion—Essenism. Sand writes:

At the time of the Khazar conversion, copies of the Talmud were still a rarity, which enabled many proselytes to take up ancient rites, even priestly sacrifices.

Evidence of the latter is the exhumation of bodies dressed in the leather garments described in the Jewish scriptures for certain temple functionaries.

Yet the kingdom was multi religious, and its law required seven judges to cover the different religions of the defendants. Moreover, some of the Khazar legends traced them to one or another of the missing ten tribes of Israel, the standard explanation of the widespread diaspora of the Jews long before they had ever been dispersed from Judea. Of course, the missing ten tribes were not Jews, they were pagan Canaanites, so the hints are that some of the original Jews of Khazaria were original Juddin of Persia.

Eventually Khazaria became known, to Russians at least, not as the land of the Khazars but as the land of the Jews—Zemlya Zhidovskaya. But, if there were Christians, Moslems and a variety of pagans in the country besides Jews, all Khazars were obviously not Jews! Who then were?

Some contemporary Arabs said the Jewish Khazars were the ruling class and the smallest but most powerful religious group. Other claimed the majority of the Khazar nation were Jews. It seems likely, if the conversion was essentially from the top down, that initially the Kagan and a few loyal nobles converted, with just a small proportion of Jews in the general population, but proselytizing among the nobility led to them all following their king. The evidence is that when this became well known to Jews elsewhere, they began to emigrate to Khazaria and spread the religion at the grass roots.

The conversion to Christianity in northern Europe was similar—the ruling class first with the peasantry following slowly. In Khazaria, Jews will have been already partially established from Armenia and the Black Sea ports, but Jewish immigration was a speeding up factor too. Another was that the Khazars traded in slaves who were always obliged to take up their master’s religion. The Khazar ruling class must have had many slaves, who had to become Jews when their masters did.

The Jewish state lasted about 300 years, so Jews were probably a significant proportion of the population by the end. Some of the Alans, a tribe related to the Magyars, were also partly Judaized, as were the Kabars who left the Khazar federation for some reason with the Magyars and moved further west into central Europe to set up Hungary, a state with a large population of Jews.

Kiev was at the western edge of Khazaria. It became the first capital of Russia, and inherited a large Jewish population from Khazaria. Kiev had both a Jewish quarter and a Khazar quarter, suggesting that all Khazars were, indeed, not Jews, and a Jews’ Gate.

The Khazar kingdom had gone by the time Rabbi Petahiah, in the twelfth century, reported on his journey from Ratisbon in Germany to Baghdad. He found that the Jews of Kedar were heretics who could not be described as Jews. They explained to him that they had never been taught Rabbinical Judaism by their parents, and had never heard of the Talmud. The heretical Jews must have been Qaraites, or they were some other local variety with traditions going back to the Persian Juddin.

The growth of Russia and its alliance with Byzantium against the Khazars led to the destruction of Khazaria in 1016 AD. Of course, the demise of the state did not mean the destruction of the Khazar Jews. Their continued existence is well documented.

It was the Mongol Horde in the thirteenth century that put paid to the old political and economic system causing the people to flee. The rice paddies and vineyards were spoilt and thereafter neglected for hundreds of years. Many Jewish Khazars fled across the steppe and marshes to Poland and Lithuania, while others hid in the Caucasus mountains.

The Zionists among Jewish historians hope to find descendants of Palestinian Jews in all Jewish history, to uphold their view of the Jews as a wandering people exiled from home. In fact the Jews of Khazaria, at their most ancient, were from Persia and Armenia, not Judea:

There had been Jewish settlements in the country before the Khazars’ conversion, even before the Khazar conquest. There had been a process of Judaization in the kingdom among other non-Khazar people. There was Jewish immigration from other countries, mainly from Moslem Central Asia, Eastern Iran, and Byzantium. Thus a large Jewish community grew there, of which the proselyte Khazars were only a part, and whose cultural character was shaped mainly by the old population of the northern Caucasus and Crimea.

A Polak, Khazaria (in Hebrew, 1951, cited by S Sand)

Polak is bowing politely to Zionist myth. The proselyte Khazars were obviously only a part of the Khazar Jewish community, but they became the largest part, and the Jews from the Caucasus (Armenia), Moslem Central Asia, and Eastern Iran were all from places that had been part of the Persian empire, and so had Juddin among their populations in the fourth century BC. All of the Persian Juddin were converts. They were the Jews.

Arthur Koestler wrote, in The Thirteenth tribe;

The large majority of surviving Jews in the world is of Eastern European—and thus mainly Khazar—origin.

It is a thesis that the scholars had widely accepted until the Zionist propaganda machine set out to cut it down. Since the 1970s, Shlomo Sand says it has been reviled as “scandalous, disgraceful and anti-Semitic”, because anything that is anti-Zionist has been defined as being anti-Semitic. But, in the past, even Zionist historians accepted it:

The first Jews who came to the southern regions from Russia did not originate in Germany... but from the Greek cities on the shores of the Black Sea, and from Asia via the mountains of the Caucasus.

A Harkavy, The Jews and the Languages of the Slavs, cited by S Sand

The Jews coming from the east met Jews moving from the Mediterranean through southern Europe and Germany in Poland and Lithuania. So, the southern Jews already spoke German when they met the Khazar Jews. German was the language of trade and business, so became the common language of eastern European Jews. It became Yiddish, Harkavy thought.

Yitzhak Schipper, a Polish Zionist, also accepted the Khazar origin of eastern European Jews. Naturally, there had been the core of Ur-Jews who introduced the Khazars to the religion, but thereafter, it was proselyte all the way, and the Ur-Jews were themselves converts!

Salo Baron, another Zionist historian, also had to acknowledge Khazaria as a significant branch off from the conventional Zionist linear Jewish history:

From Khazaria, Jews began drifting into the open steppes of Eastern Europe, during both the period of the country’s affluence and that of its decline... After... the decline of the Khazar empire... refugees from the devastated districts, including Jews, sought shelter in the very lands of their conquerors. Here they met other Jewish groups and individuals migrating from the west and south. Together with these arrivals from Germany and the Balkans, they began laying the foundations for a Jewish community which, especially in sixteenth century Poland, outstripped all the other contemporary areas of Jewish settlement in population density as well as in economic and cultural power.

S Baron, cited by S Sand

Ben-Zion Dinur, an Israeli Minister of Education concurred with Polak and Baron. Russia diminished the Khazar kingdom, absorbing it, but that did not mean an wholesale slaughter of the people. It became “a diaspora mother”, the mother of the Jewish diaspora in Russia, Poland and Lithuania.

The Yiddish language is 80 per cent German, but there is no direct evidence that German Jews had gone east as Harkavy thought.

The evidence is that, until the seventeenth century, the eastern Jews spoke the local Slavonic language. What was also true was that Germans had moved east setting up German colonies all the way to the Volga river in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and it seems that it was the displaced Jews who acted as intermediaries between the German artisans and merchants and the local people.

Four million Germans lived in Poland. Jews became carters, woodworkers and coin makers, serving the German colonists. They spoke Polish naturally, but had to learn German to serve their clients. They started then speaking a mixture at home and in their own community to teach their kids the language of the traders. They then began to use German in their own transactions. Thus Yiddish evolved.

Now, as Yiddish has no western European words in it, it is certain that the German Jews from the Rhineland had no influence on it. Paul Wexler, the Israeli linguist, traces Yiddish words to their Slavonic languages, and to southeastern German. He sees Yiddish as akin to Sorb, a different mixture of Slav and German. As to the source of such large numbers of eastern European Jews, it is quite impossible that they could have come from Germany. In the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, when the Khazar kingdom was in decay and could offer a large pool of Jews for migration west, there were only a few thousand Jews at the most in the west of Germany. Occasionally they were persecuted in pogroms, but they rarely had to flee far or for long, and most returned home when the xenophobia had calmed down.

For Yiddish to develop, whole Jewish communities were needed. They did not exist in the west. In Western Europe, Jews were present in quite small groups in urban areas working for others and speaking their language, yes. But the Yiddish speakers in the east were larger communities, whole villages in which the hybrid language could develop a life of its own. They were separate settlements with their own synagogue topped with a cupola of typical eastern style. Their dress was eastern differing significantly from that of Slav peasants, and Yiddish has a peculiar preponderance of words of Turkic origins, like yarmulka and davenen.

Finally, Sand tells us that 80 per cent of the Jews of the world were Yiddish speakers at the turn of the twentieth century. So we have Jewish Khazaria succumbing to Slavic conquerors, the Russians, then a few years later, Jews began to be recorded as appearing in Poland and Lithuania.

Of course, from the local Catholics, they all had the Christian story of the diaspora of Vespasian after the Jewish War, and it did not take many generations before their real origins in Khazaria, and ultimately Armenia and Persia were forgotten.

For more on Judaism and Khazaria fead Dr Magees full paper

https://www.academia.edu/22882969/How_Persia_Created_Judaism?auto=download

Or here