Hoover and the American Rescue Administration in Russia during the Civil War and Famine

Perhaps one of the most underestimated Americans is Herbert Hoover.

Excerpts from “The Russian Job: The Forgotten Story of How America Saved the Soviet Union from Ruin”

Hoover was made a partner in the British engineering firm Bewick, Moreing and Company and traveled about the world setting up and reorganizing mining operations in sixteen countries. He had a knack for making lackluster operations profitable and discovering new opportunities. In 1905, Hoover invested his own money into an abandoned mine in Burma, and under his management it quickly became one of the world’s richest sources of silver, zinc, and lead. He gained an international reputation for his administrative talent, technological understanding, and way with finances.

After a few years, he parted company with the firm and went off on his own, operating simply as “Herbert C. Hoover,” with offices in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, and St. Petersburg.

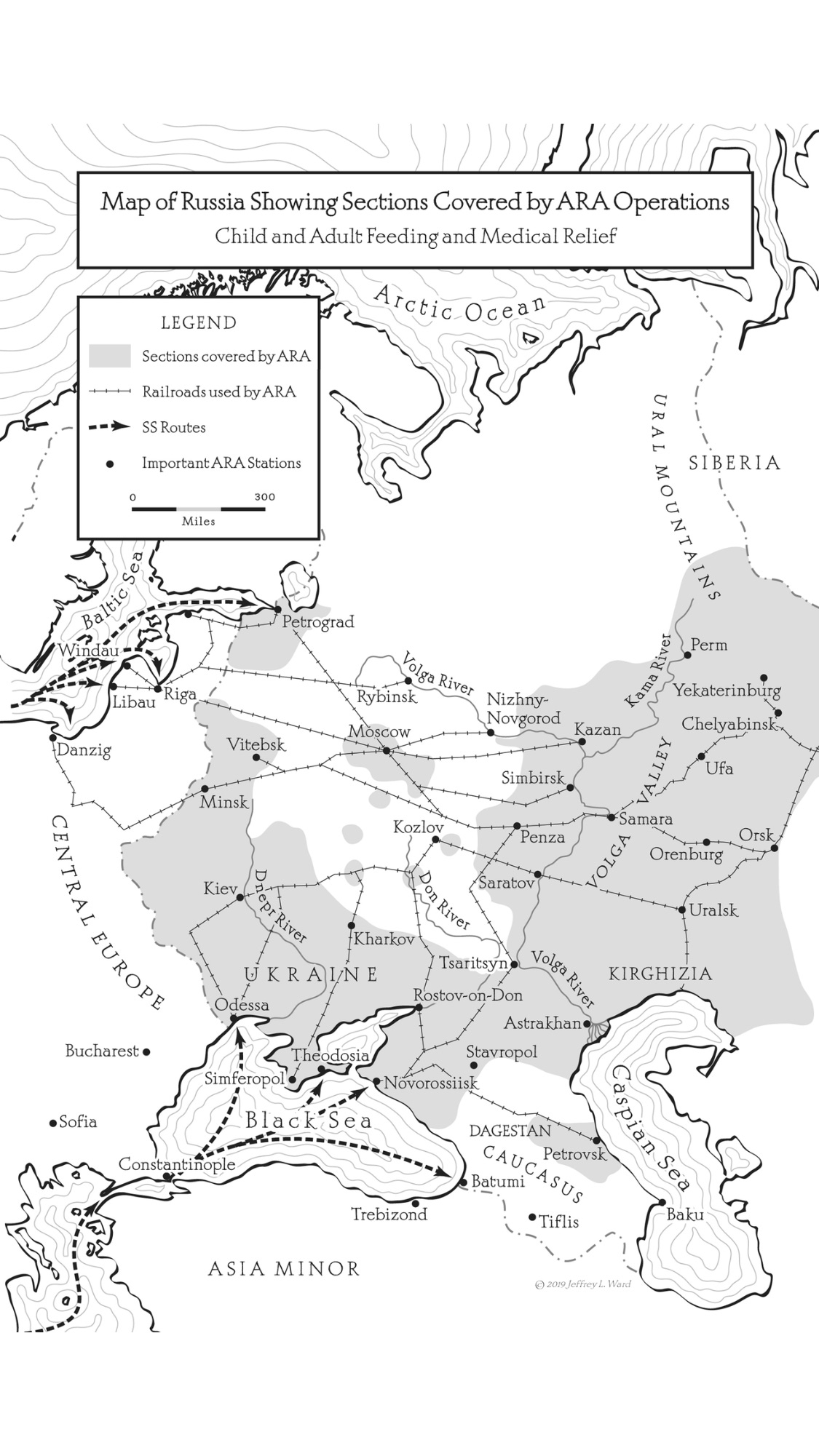

Hoover first visited Russia in 1909, and over the next several years he invested considerable time and money in the country. He was involved in oil fields around the Black Sea, copper mines in the Kazakh Steppes, gold and iron mines in the Ural Mountains. At one point, he was even asked to manage the Romanov Imperial Cabinet’s mines.

He returned to Russia two years later to check on his investments. Although pleased with the state of his various operations, Hoover was disturbed by what he saw of Tsar Nicholas II’s Russia. He described as “hideous” the social tensions rumbling just beneath the surface. The sight of a chain gang being marched off into Siberian exile made him shudder. The brutality of the tsarist system haunted Hoover: he couldn’t shake the feeling that, in his words, “some day the country would blow up.”

Hoover sold off his investments before the country exploded under the joint pressures of war and revolution. Russia, for Hoover, was a land filled with “annoyance and worry.”

During WW I Hoover urged the president to create the American Relief Administration, funded by a $100 million appropriation from Congress early in 1919. As its general director, Hoover undertook relief operations in thirty-two countries, not only offering food and clothing but rebuilding devastated infrastructure and acting as a quasi-intelligence and diplomatic organization for the Allied powers.

Hoover wrote Secretary of State Robert Lansing from Paris in August 1919 that the ARA should support the White Army forces of General Nikolai Yudenich, convinced that the Whites represented Russia’s best hope for a constitutional government and the defense of personal liberty. When Yudenich marched on Petrograd in the autumn, Hoover supplied him with food, clothing, and gasoline. The grateful general wrote to thank “Mr. Hoover, Food-Dictator of Europe,” and informed him that his army was “now existing practically upon American flour and bacon,” which was no less important for their success than “rifles and ammunition.”

Hoover later tried to cover up his support of the Whites, but Lenin and the rest of the Soviet leadership knew about it. Understandably, the true motives of America’s great humanitarian remained under a cloud of suspicion.

Apparently, the idea had not belonged to Gorky, who was no great champion of the peasantry. (He even published a book the following year called The Russian Peasant in which he wrote of “the half-savage, stupid, and heavy people of the Russian villages” and expressed the hope that they would die out and be replaced by “a new tribe” of “literate, sensible, hearty people.”) Friends of the writer convinced him to use his considerable moral authority to speak with the Kremlin about issuing an open appeal to the world. Lenin, it seems, did not take much convincing.

On July 22, 1921, a copy of Gorky’s appeal published in the American press landed on the desk of Herbert Hoover, the U.S. secretary of commerce. As soon as he had read it, Hoover knew what had to be done.

Hoover, wrote to Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes: “I feel very deeply that we should go to the assistance of the children and also provide some medical relief generally.” He stated that he wished to reply to Gorky’s appeal. “I believe it is a humane obligation upon us to go in if they comply with the requirements set out; if they do not accede we are released from all responsibility.” Hoover could not have been surprised by Gorky’s appeal. In the first week of June, the ARA received reports on the severity of the Russian crisis. Hoover communicated to his top subordinates in the ARA that operations in other countries were to be halted so that they could begin building up supplies for a possible mission to Russia. He wanted to be ready, should the Soviet government collapse or be overthrown, to show Russia the goodwill of the American people. His motives were twofold: the desire to fight both hunger and Bolshevism.

Paul Ryabushinsky, an adviser to the embassy of the Russian Provisional Government in Washington, D.C., met with Hoover’s assistant Christian Herter to tell him in secret that Russian émigrés were prepared to provide money and supplies to the ARA that it could funnel to the All-Russian Committee for Aid to the Starving. Their goal was to use the ARA to help undermine the Soviet government and replace it with the committee once the Soviets had been overthrown. Herter declined to endorse Ryabushinsky’s plan.

All of this was taking place in the shadow of the Red Scare that had gripped the United States in 1919–20. After the war, the country had experienced a wave of strikes and worker agitation, and there was the fear that Bolshevik influence might spread outward from Russia to destabilize the West. The U.S. Senate organized a subcommittee to investigate the threat of the “Red Menace” to civilization. In the spring of 1919, anarchists began a bombing campaign against key politicians, state officials, and businessmen, including John D. Rockefeller. One bomb was mailed to the home of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. An enraged Palmer responded with the so-called Palmer Raids.

By December, radicals had been caught and placed on a ship leaving for Finland, whence they would be free to make their way to Bolshevik Russia. Among them was the “Red Queen,” Emma Goldman. One of the young agents hired by Palmer to hunt down the radicals was a nineteen-year-old civil servant by the name of J. Edgar Hoover. In the end, thousands of suspected radical subversives were deported. Palmer announced that the Reds planned to overthrow the U.S. government on May 1, 1920. When

On July 23, Hoover wired a lengthy telegram to Gorky, explaining that he had been moved by the suffering of the Russian people and laying out what had to happen before any aid might be considered, as well as a necessary general understanding of principles. First, he noted, all American prisoners in Russia had to be released immediately. Next, the following items had to be agreed to: (1) that the Soviet government must officially state that it was requesting the assistance of the American Relief Administration; (2) that Mr. Hoover was acting not as secretary of commerce but in an unofficial capacity, as the head of a relief agency, so that help from the ARA in no way signaled official U.S. government recognition of the Soviet state; (3) that the ARA would operate in Russia as it did in all other countries: namely, its workers would have complete liberty to come and go and travel about, free of interference; that they would have permission to set up local aid committees as they best saw fit; and that the Soviet government would cover all costs associated with the transportation, storage, and handling of ARA supplies.

In return, the ARA promised to give food, medical supplies, and clothing to one million children “without regard to race, creed, or social status.” Finally, Hoover affirmed that the representatives of the ARA would refrain from any political activity.

On July 26, a mere three days after sending his list of conditions, Hoover received a reply from Gorky stating that the Soviet government looked favorably on his offer. Two days later, Lev Kamenev, an old Bolshevik, a longtime comrade of Lenin, chairman of the Moscow Soviet, and head of the Committee for Aid to the Starving, sent Hoover an official letter of acceptance of relief on behalf of the government. He promised that the American prisoners would be freed and proposed that the two sides immediately sit down to agree on the conditions necessary to begin the enormous task of feeding the hungry.

In the middle of August, a meeting was convened in Geneva by a number of Red Cross societies to discuss the possibility of organizing aid to Russia. They established the International Committee for Russian Relief and elected Fridtjof Nansen, to whom Gorky had first sent his appeal for help, as its high commissioner.

The Nansen mission, as it was known, brought together relief organizations from over twenty countries. Among the groups that came to Russia’s aid were the British Society of Friends, the Save the Children Fund, the Red Cross of Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, and Belgium, and His Holiness the Pope. Nansen left Geneva for Moscow, where he was warmly embraced by top Soviet officials, in large part because he was much more cooperative than Hoover and the ARA.

Nansen had no serious experience in relief operations, nor did he have a large organization at his disposal, and so he offered to turn over to the Soviet government whatever supplies he managed to gather. The Soviets could not have been happier. The relief provided by the Nansen mission was significant, although modest when compared with what the ARA provided: approximately 90 percent of all aid delivered to Russia came from the Americans.

On October 25, the Cheka issued a special order giving all agents extraordinary powers of surveillance in the struggle against the ARA. “Based on our intelligence, the Americans are drawing anti-Soviet elements into the ARA organization, engaging in espionage to gather information on Russia, and buying up valuables.”

Hoover had decided to use the congressional appropriation to force the Soviets to contribute more to the famine-relief effort. Back in late August, he had communicated to Brown that he wanted to convince the Soviets to use some of their gold reserves to help defray the expense. The Soviets had agreed to provide the ARA with $4.5 million in gold to be used to purchase American grain, at cost. Now, however, Hoover upped the figure. He informed Leonid Krasin, the people’s commissar for foreign trade, that the ARA expected $10 million in Soviet gold to be used to purchase seed and grain for feeding operations in the Volga Basin. Krasin wired Moscow of Hoover’s demand, and Lenin replied immediately that he should accept the new terms, so great was his desire to secure further American aid.

Despite the challenges, the men of the ARA carried on. By the end of 1921, the famine had gotten worse—perhaps as many as thirty-six million men, women, and children now faced starvation. The question on everyone’s mind as the horrific year came to an end was whether the American relief would arrive in time to save them.

When Golder was in Moscow at the end of January, he learned that his report on conditions in Ukraine had been important in the decision to begin aid there; on the 10th of that month, Haskell signed a separate treaty with the Ukrainian authorities that essentially copied the provisions laid out in the Riga treaty with Russia. The size of the ARA’s job had grown enormously, adding eighty-five thousand square miles and ten million people. The relief was desperately needed: by April, an entire third of the Ukrainian population was facing starvation

By 1923 the ARA had saved millions of lives. According to the Soviet press, it had fed eleven million people—almost a tenth of the population—in twenty-eight thousand towns and villages and distributed over 1.25 million food parcels. It had restored fifteen thousand hospitals serving eighty million patients and inoculated ten million people against a variety of epidemic diseases. No reliable records were kept on the number of famine victims; the estimates range from as many as ten million to as few as one and a half million. A reasonable figure would be over six million excess deaths from starvation and disease, making this one of the worst famines in world history, behind the Chinese famines of 1877–79 (over nine and a half million dead) and 1959–61 (over fifteen million) and the Indian famine of 1876–79 (roughly seven million excess deaths).

And how many lives did the ARA save in the end? This is even more difficult to answer, although, when one considers both food relief and medical intervention, an estimate of more than ten million does not seem exaggerated.

The first arrests appear to have begun not long after the Americans’ departure in July 1923. The GPU arrested a former nobleman by the name of Palchich who had worked for the ARA and accused him of being a spy and having provided the Americans with secret maps of the Baku oil fields for use in a planned American invasion. A certain N. Belousov, the son of a tsarist officer and an inspector for the ARA in Simbirsk, was arrested; he purportedly admitted under questioning that his anti-Soviet views had led him to cooperate with American agents embedded in the ARA. Among his supposed crimes was gathering information for the ARA on the economic conditions and food supply in one remote district.

One of Childs’s assistants, a woman named Molostova, was also imprisoned as an agent of the United States. Proof of her treachery was that, upon Childs’s request, she had translated Russian books about the Soviet economy and agriculture.

Workers took down the signs outside the Blandy Memorial Hospital and the Blandy Children’s Home soon after the ARA pulled out of Ufa. If the proposed monument to Blandy was ever built, it’s no longer there now. In Odessa, the Haskell Highway and Hoover Hospital were quietly renamed. Several of the officials with whom the Americans had worked and who knew the truth about the ARA’s mission fell victim to Stalin’s terror in the late 1930s. Kamenev, Radek, Eiduk, Lander, Kashaf Mukhtarov, Rauf Sabirov—all were executed as enemies of the people.

In May 1924, under the headline “ARA Spies in Role of Philanthropists,” Izvestiia reported the arrest of two Soviet citizens on charges of economic espionage. One of them was sentenced to ten years in prison; the other, five. Hoover was outraged. “While the imprisonment of those assistants continues,” he told the press, “it will form an impassable barrier against any discussion of the renewal of official relations.” Secretary of State Hughes agreed with Hoover, as did first President Harding and then his successor, Calvin Coolidge.

Official recognition of the Soviet Union would have to wait another decade, until November 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt established normal diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Although this recognition did not come until a full decade after the end of the ARA mission, relations between the Soviet Union and the United States had not stagnated during the 1920s. Just the opposite. Harding and Coolidge, with the support of Hoover as secretary of commerce, may have opposed official relations, but they did nothing to prevent American firms from doing business in Russia, and even began to encourage them. Between 1923 and 1930, the sale of American goods to the USSR grew more than twentyfold, from $6 million to $140 million per year, and overall trade between the countries during that period surpassed $500 million, most of which consisted of American exports to Russia.

A quarter of all Soviet imports came from the United States, representing a range of products but especially heavy equipment for use in mining, agriculture, construction, metalworking, and the oil-and-gas industry.

Large credits flowed into the Soviet economy from banks such as Chase National, Guaranty Trust, and Equitable Trust and firms such as General Electric and the American Locomotive Sales Corporation, especially after Hoover lobbied the administration to loosen restrictions on private loans.

By 1928, American companies were offering Moscow large, long-term financing deals, as much as $25 million over five years. Trade with the United States surpassed that with countries such as Britain, which had signed a trade pact with the Soviets in 1921 and established diplomatic relations three years later.

The rhetoric against the ARA heated up during the Cold War. According to the 1950 edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, the ARA had been established solely “to create an apparatus in Soviet Russia for spying and wrecking activities and for supporting counterrevolutionary elements.” Not a single reference was made to the Americans’ relief operations.

A standard history textbook from 1962 explained to schoolchildren that Hoover had sent the ARA to Soviet Russia “to secretly organize an insurrectionary force,” but thanks to the vigilance of the Cheka and GPU, his plot was uncovered, the ARA’s Russian counterrevolutionary agents were arrested, and America’s plans to overthrow the first communist government were thwarted.