Just reread a fascinating book by the son of one of Israels greatest Generals from 1948-1967. I strongly recommend it to better understand the history as told by the son of a Israeli military leader.

https://www.amazon.com/Generals-Son-Journey-Israeli-Palestine/dp/1682570029

For some reason its no longer available on kindle and priced at $17 for a 270 pg paperback.

While the son has a fascinating story himself I am going to limit this to what he writes about his Father who became known by the Palestinians as the Father of Peace, a proponent of a two state solution following the expansion of Israels borders following the 1967 War. The War was also known as the Six-Day War when the Israeli army captured the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. He later became a professor of Arabic language and literature, a member of Israel’s parliament, and a peace activist.

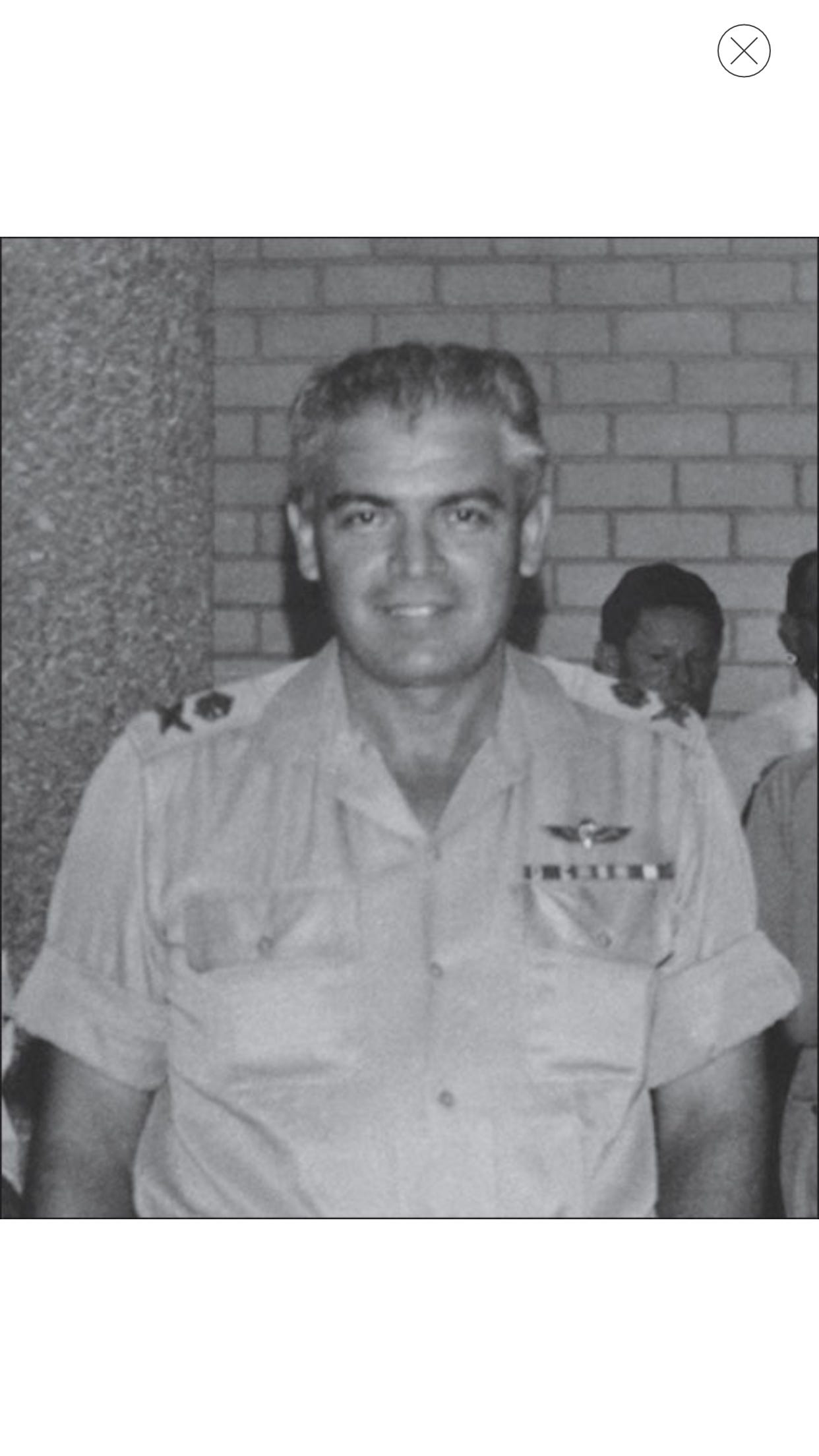

Matti Peled was a career officer who dedicated himself to building a well-organized fighting force for the young state of Israel

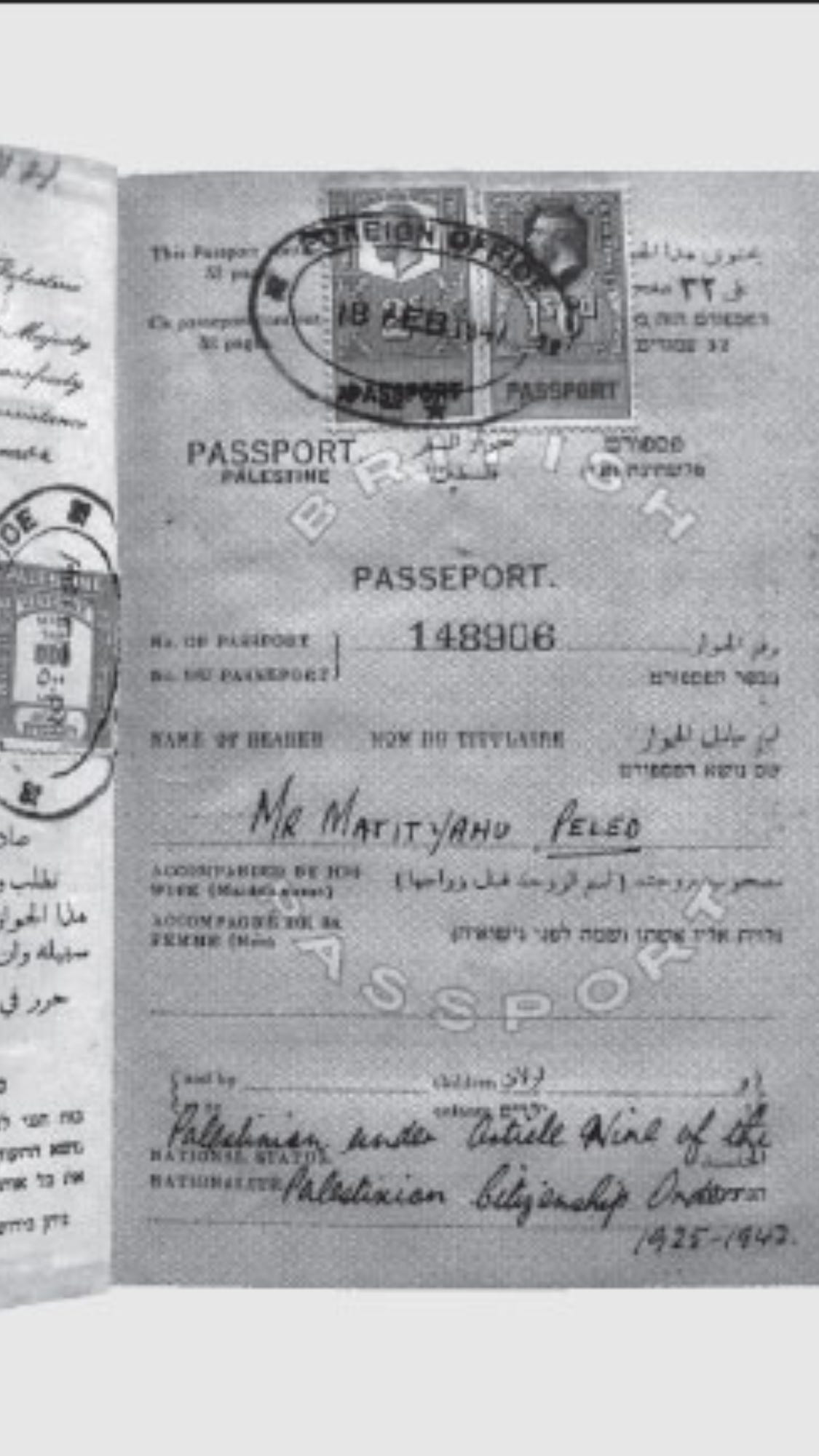

His passport, issued by His Majesty’s Government, stated under “country”: Palestine. And under “citizenship”: Palestinian.

In the fall of 1947, hostilities erupted—a war that would later be called Israel’s War of Independence had begun. He served as a captain in the Givati Brigade’s 51st regiment, and commanded the second infantry company, or Company B. The role of Company B became the stuff of legends.

In October 1948, the company took part in a crucial battle as part of Operation Yoav—which coincidentally shared my brother’s name—to claim the Negev region, in the southern part of the country. The company suffered many casualties, their communication was lost, and two officers died in battle. He was seriously wounded twice during the battle. Once communication was restored, he was instructed to retreat but insisted they carry on—a third of the company was injured, and there was no one to carry the wounded. He maintained that they could hold on and complete their mission.

Later in the book his son learns of an alternative history from a Palestinian he would become friends with. His friend said:

The Palestinians had barely 10,000 fighters, but the Haganah and the other Jewish militias combined were triple that number if not more. So when the Jews attacked, the Palestinians never had a chance.”

That was the most outrageous version of history I had ever heard: that the fighting forces of the Jewish militias in 1948 were superior to the Arabs’ and that the Jews attacked.

[I then read] books by Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, and Avi Shlaim.” These three “New Israeli Historians” had all recently rewritten the history of the establishment of Israel…... And the more I read, the more I wanted to know. They had corroborated what Palestinians had been saying for decades. In fact, they corroborated what most of the world had known for years: that Israel was created after Jewish militias destroyed Palestine and forcibly exiled its people.

Many if not all of these myths were created and perpetuated by the new Jewish state, which wanted to substantiate the David versus Goliath image and painted my people as heroes who rose from the ashes to reclaim their historic homeland.

Anyways, back to the Generals story

In 1956, Ben-Gurion signed a secret pact with France and Britain to attack Egypt. Israel conquered the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula in what was called the Sinai Campaign, or Mivtza Kadesh. The war lasted from October 29 to November 5. Israel suffered 171 casualties, and the Egyptians lost between two and three thousand men. Israel captured 6,000 POWs and the Egyptians captured four Israelis.

Just as Ben-Gurion and Dayan had anticipated, it was a devastating blow to the Egyptian army. This was the first time Israel had occupied the Gaza Strip—an artificially delineated region on the southeastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea surrounding the ancient city of Gaza—where Palestinians refugees exiled in 1948 were herded.

After the Sinai Campaign, by then a full colonel, my Father was appointed military governor of the Gaza Strip. This was a defining role for him, and it influenced his entire life.

As military governor of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, he prealized that he knew virtually nothing of their language, culture, or their way of life. He did not like the fact that he needed translators in order to communicate with the people he governed, so he made a personal decision to study Arabic, receiving a bachelor’s degree in Arabic from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

“In conversations with the locals, I was amazed to learn that they were not seeking vengeance for the hardship we caused them, nor did they wish to get rid of us. They were realistic and pragmatic and wanted to be free.”

Under immense pressure from the Eisenhower administration, Israel was forced to give up the conquered territories in March of 1957. Although in those days Israel was receiving no money from the U.S. government.

His next major assignment was commander of the Jerusalem Brigade, which secured and protected West Jerusalem’s precarious border with Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem. Jerusalem was not just another region. Jews, Christians, and Muslims had a deep regard for the city, which meant that he had dealings with diplomats and religious leaders from all around the world. It was a highly sensitive diplomatic post as well as a difficult military one.

In the early 1960s, he served as special advisor on armaments to the deputy minister of defense, who at the time was Shimon Peres. This was the period when, under Peres’s supervision, Israel began developing its nuclear weapons program. It was one role about which my father never spoke

In 1964, he was promoted to major general (aluf in Hebrew) as chief of logistics of the Israeli army. This is the highest rank in the Israeli army with the exception of one person, the army chief of staff. His responsibilities included armaments, technology, logistics, the medical corps, weapons and other purchases, and overseeing an enormous budget. ……chief of logistics was an important position that carried a great deal of responsibility, and the state of logistics in the army was in dire need of reform. So army chief of staff Yitzhak Rabin nominated him to that position, and he remained in it for four years.

In the late spring of 1967, Egypt’s President Nasser expelled the United Nations peacekeeping forces that had been monitoring the ceasefire between the two countries from the Sinai Peninsula. He sent Egyptian troops across the Suez Canal and into the demilitarized Sinai Peninsula, and he threatened to blockade the straits of Tiran and not permit Israeli ships to proceed toward the Israeli port city of Eilat. These were acts that blatantly violated the terms of the cease-fire that was signed between Egypt and Israel. The army was calling it a plausible casus belli, or justification for war.

According to documents found in the IDF archives and other sources, the Soviet government fed misinformation to the Egyptians, claiming that Israel was planning a surprise attack against Syria. The Soviets claimed that Israel had amassed troops on the border with Syria. Syria and Egypt had a mutual security pact, and President Nasser had to act in defense of his Syrian allies.

As the Israeli cabinet was considering its options, on May 26, 1967, the Russian prime minister sent the Israeli prime minister, Levi Eshkol, a letter through the Soviet ambassador in Tel Aviv, calling for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. When the Russian ambassador presented Prime Minister Eshkol with the letter, Eshkol invited the ambassador to see with his own eyes that the claim had no merit and that Israeli troops were not amassed at the Syrian border.

The army was recommending that Israel initiate a preemptive strike against Egypt. The cabinet was hesitant and wanted time to explore other options before committing to a full-scale war. Things came to a head in a stormy meeting of the IDF General Staff and the Israeli cabinet that took place on June 2, 1967.

After opening remarks, my father told the cabinet in no uncertain terms that the Egyptians needed a year and a half to two years in order to be ready for a full-scale war. The other generals agreed that the Israeli army was prepared and that this was the time to strike another devastating blow.

During this meeting, he said to the prime minister, “Nasser is advancing an ill-prepared army because he is counting on the cabinet being hesitant. He is convinced that we will not strike. Your hesitation is working in his advantage.” In his reply , the prime minister said, “The cabinet must also think of the mothers who are likely to become bereaved.”

General Ezer Weizmann, a lifelong friend of his, threatened to resign his post as deputy chief of staff. General Ariel Sharon, who many years later would be prime minister, said that Israel must engage in a preemptive strike against the Egyptian army “and destroy it entirely without delay.”

The army decided to announce that “The delay in attack is due to diplomatic considerations, but the existential threat remains imminent.” Israeli citizens were led to believe that the Arab armies were coming to rape and murder them, as the Nazis had done less than three decades earlier.

The surprise attack led to the total destruction of Egypt’s air force, the decimation of the Egyptian army, and the re-conquest of the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula in a matter of days.

Israeli army intelligence confirmed that the Syrian and the Jordanian armies were no match to the IDF. After the campaign against Egypt went smoothly, the field commanders, in collusion with Moshe Dayan, decided to take the West Bank and the Golan Heights, two regions Israel had coveted for many years. Both had strategic water resources and hills overlooking Israeli territory. The West Bank contained the heartland of Biblical Israel, including the “crown jewel,” the Old City of Jerusalem.

The fact that the West Bank and the Old City of Jerusalem remained in Arab hands in 1948 was a sore spot for many of the senior officers. So when the opportunity arose again they acted swiftly and decisively. They referred to it as “finishing the job.”

In six days, it was all over. Arab casualties were estimated at more than 15,000. Israeli casualties were 700, and the territory controlled by Israel had nearly tripled in size. Israel had in its possession not only land and resources it had wanted for a long time, but also the largest stockpiles of Russian-made arms outside the Soviet Union. Israel had once again asserted itself as a major regional power.

But this massive conquest of lands troubled him. When he was pushing for the war, he had imagined it would be a limited war with Egypt to punish the Egyptians for their breach of the ceasefire and to assert Israeli legitimacy and military might. Taking the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Golan Heights was never part of any official plan. In an article in the daily Ma’ariv, journalist Haim Hanegbi vividly describes the first weekly meeting of the General Staff after the Six-Day War.

He states that Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin and the other generals were beaming with the glory of victory, but when the meeting was nearing its end, my father spoke. Never one to rest on his laurels, he cleared his throat and in his unmistakably dry, analytical manner, he spoke of the unique chance the victory offered Israel to solve the Palestinian problem once and for all. “For the first time in Israel’s history, we are face to face with the Palestinians, without other Arab countries dividing us. Now we have a chance to offer the Palestinians a state of their own.”

He later also claimed with certainty that holding onto the West Bank and the people who lived in it was contrary to Israel’s long-term strategy of building a secure Jewish democracy with a stable Jewish majority. If we kept these lands, popular resistance to the occupation was sure to arise, and Israel’s army would be used to quell that resistance, with disastrous and demoralizing results. He concluded that this would turn the Jewish state into an increasingly brutal occupying power and eventually into a bi-national state.

He had no interest in governing an occupied nation, and he was eager to move on with his life. So in 1968, he opted to retire from the army and embark on a much-anticipated academic career. He donated his huge military library to the IDF and filled his study with books on Arabic literature.

immediately after he retired from the army, his family moved to Los Angeles for three years in order for him to pursue his second career, as a professor of modern Arabic literature. During this time, he managed to complete his PhD at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

While he was still in the United States,he started writing a weekly opinion column in Ma’ariv, a mass-circulation daily newspaper published in Israel. Because of his résumé, everyone expected him to align himself with the Israeli government’s narrative, which claimed that Israel had been viciously attacked by three Arab armies in 1967 and defended itself heroically because it had the wits and, more importantly, the moral high ground. This narrative also claimed that Israel’s rights to the land of Israel were absolute, if not for religious or historical reasons then for military and security reasons.

But he saw things differently. He came out and stated publicly that the 1967 War was not an existential war but a war of choice:

I was surprised that Nasser decided to place his troops so close to our border. He must have known the grave danger into which he placed his forces. Having the Egyptian army so close allowed us to strike and destroy at any time we wished to do so, and there was not a single knowledgeable person who did not see that. From a military standpoint, it was not the IDF that was in danger when the Egyptian army amassed troops on the Israeli border, but the Egyptian army.

He fiercely criticized the army’s building of an expensive defensive line in the Sinai Desert along the shores of the Suez Canal. He thought the army should be mobile and agile and that throughout history defensive lines had proven themselves to be costly and ineffective.

This line was later named Kav Bar-Lev, or The Bar-Lev Line, after Chief of Staff Haim Bar-Lev. During the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, the Egyptian army stormed through the Bar-Lev Line and it proved to be a disaster, providing no defense at all. After the war everyone liked to joke:

Question: What remained of the Bar-Lev Line after the war?”

Answer: The villas of the contractors who built it.

That does remind one of Israels billion dollar Iron Wall along Gaza’s border on 10/7, doesn’t it. Main difference is Egypt had a real Army.

In 1973, Prime Minister Golda Meir gave a speech in the southern Israeli city of Eilat, in front of an audience of high school students. It was during this speech that she claimed that, before 1967, she had never heard of the Palestinian people and that they were somehow invented and had no real national identity—and therefore could have no national claims to the land of Palestine.

In his column, he immediately wrote a scathing reply to Golda’s speech where he asked: How do people in the world refer to the population that resides in the West Bank? What were the refugees of 1948 called prior to their exile? Has she really not heard of the Palestinian people prior to 1967? In discussions she must have had over the years in her capacity as ambassador and then as foreign minister, how did she refer to these people? Yet she says she had not heard of the Palestinian people prior to 1967? Truly amazing!

Still, it came as a shock when, in the mid-1970s, he called on the Israeli government to negotiate with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the PLO. He argued that the PLO was the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and as such must be Israel’s partner to the negotiating table. He claimed that Israel needed to talk with whoever represented the Palestinian people, the people with whom we shared this land. He constantly wanted to remind everyone that only peace with the Palestinians could ensure our continued existence as a state that was both Jewish and democratic.

“How can you talk to terrorists who want our destruction?” some would ask. “They want Yaffa and Haifa and Ramle, and they want to slaughter all of us.” “Terrorism,” he would reply, “is a terrible thing. But the fact remains that when a small nation is ruled by a larger power, terror is the only means at their disposal. This has always been true, and I fear this will always be the case. If we want to end terrorism, we must end the occupation and make peace.” He insisted that the Palestinians could become our natural allies, our bridge to the entire Middle East, where we Israelis had decided to build our home.

He did not accept the double standard that we, the Jewish people, deserve to live on the same land as the Palestinians and yet deprive them of their rights. He also had grave concerns for the nature of the Jewish democracy, and he knew that the occupation of another people would destroy the moral fiber of society and of the IDF. He did not want to see the IDF turn into a brutal force charged with oppressing a nation that would surely rise to resist the occupation.

Over the years, his views became more and more at odds with mainstream Israel, even though in theory everyone claimed to espouse the principles he preached: democracy, free speech, and above all, peace.

Then, along with Avnery, Yaakov Arnon, and several other dissident members of the Zionist establishment, he founded the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace. The council sought to promote private and unofficial dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians, which they hoped would lead to official negotiations between Israel and the PLO. Its charter called for Israel to withdraw from the territories occupied in 1967 and for an independent Palestinian state to be established in the West Bank and Gaza, with Arab East Jerusalem as its capital. At the time, the idea was unthinkably radical.

PLO had a policy of talking only to non-Zionist Israelis who were open to the idea of a “secular democracy” in all of Israel/Palestine, where Jews and Arabs would live in one state. This notion was totally unacceptable to him : He was a Zionist—he believed in a state for the Jewish people in the Land of Israel. For him, any other solution would lead to endless bloodshed.

It was in Paris where he was first introduced to Dr. Issam Sartawi, a close confidant of Yasser Arafat and the PLO’s representative to Paris.

The contacts between members of the council and the PLO were largely kept secret, as few Israelis could comprehend the idea of talking with the Ashaf, and many Palestinians were fiercely opposed to a dialogue with Zionist Israelis. Over the years, Issam and his wife, Dr. Widad Sartawi, developed a personal friendship with my father and mother.

Whenever Dr. Sartawi called him from Paris, his code name was The Friend. “Hello, is Matti home? This is the friend speaking.”

One discussion they had was about creating a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, what was later named, “The Two-State Solution.” For Yasser Arafat to give up all of Palestine with the exception of the West Bank and Gaza—two pockets of land that amount to 22 percent of Palestine—was an enormous concession to make before official negotiations began. The official line of Fatah—a main Palestinian liberation party and a major faction of the PLO—was to support one secular democratic state that would include Arabs and Jews and allow the return of the Palestinian refugees. Arafat had serious people around him who saw the two-state solution as an option that was both pragmatic and practical. Others within Fatah vehemently disagreed, claiming they could not abandon the millions of refugees who wanted to return to their homes and land in what was now Israel. Arafat had to tread carefully between these two camps. He wouldn’t officially endorse a two-state solution until 1988, but the idea was born in these early years when he let his advisors speak with prominent Zionists.

In 1977, Israeli Television set up a roundtable discussion with the entire general staff of 1967—on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the war. The roundtable was held on a news program called Moked, and was later featured in the excellent documentary by Ilan Ziv that came out in 2007 called Six Days in June. At one point, my Father remarked that he did not recall ever hearing or seeing a directive from the cabinet to take the West Bank. It was the first time that I heard him criticize the IDF commander’s decision to take the West Bank without first seeking cabinet approval. “It had always been considered an important strategic directive to avoid conquering areas that were heavily populated,” he said. “Taking the West Bank with its Arab population was a clear reversal of this principle, and I don’t recall ever hearing or seeing such a directive come down from the Israeli government.” As he was saying this, the camera began pulling back to show the faces of the others around the table. Their unease at his words was obvious. Not only was my father reminding everyone that the West Bank and the Golan Heights were taken without cabinet approval, an act that in the past he had defended, but he was now pointing out that the generals themselves reversed an important strategic directive without proper authority.

Riding the success of the 1979 peace pact with Egypt, in the 1982 national elections Menachem Begin won a second term in office as prime minister. However, this term was marked by the invasion of Lebanon, a devastating war that would later be known as Israel’s Vietnam.

Testing the limits as he always did, in early 1983, shortly after Arafat was driven out of Lebanon by the Israeli invasion, he embarked on a secret mission to Tunisia to meet with the PLO chairman himself. He was joined by Uri Avnery and Dr. Yaakov Arnon, an economist, former general director of the Israeli department of treasury and a close friend of my father. And on the Palestinian side, along with Chairman Arafat, were Mahmoud Abbas and Dr. Issam Sartawi. The meeting was later publicized, and the photo of them together made the press worldwide.

It wasn’t long after this historic meeting that Dr. Sartawi was murdered. It happened April 10, 1983, during a meeting of the Socialist International Conference in Portugal. The presumed culprit was the Abu Nidal terrorist gang operating out of Iraq, whose loyalties are shrouded in mystery to this day.

Later on,my Father gave a statement in which he said, “Sartawi was killed because he was reaching out to Zionists. He had literally given his life for peace.” He reminded people of this each time doubt was cast upon the sincerity of the Palestinians’ desire for peace.

“Until 1974,” he told the audience of Temple Emanuel in San Francisco on one occasion, “Israel had not received foreign aid money and we did fine.” He then looked at the people seated in the audience and continued: “Receiving free money, money you have not earned and for which you do not have to work, is plain and simply corrupting.” He argued that the weapons the United States sold to Israel were corrupting the country and were being used to maintain the occupation and oppression of the Palestinians. “It is bad for Israel, it is morally wrong, and it is illegal,” he always said.

At the end of 1992, Yitzhak Rabin was elected as prime minister once again, vowing to make peace. By the end of 1993, he seemed to come to the same conclusion as my father, and he signed the Oslo peace agreement known as the Oslo Accords and shook hands with Yasser Arafat. This was done on the White House lawn

My Father strongly supported the Oslo Accords at first, and he wrote that Rabin had “crossed the Rubicon.” (He was referring to Julius Caesar and his army crossing the Rubicon River upon Caesar’s return to Italy. In other words, it was an irreversible act of great significance.) They were signed the same year my father, Uri Avnery, and others formed Gush Shalom, the grassroots Israeli peace bloc.

But as time wore on, my Father lost patience. “Settlement expansion in the West Bank continued, and good faith deadlines passed due to Israeli inaction,” he claimed. He knew that a slow pace of peace coupled with ongoing settlement expansion would give ample opportunity to extremists on both sides to renew the violence. He criticized and described what he saw: “Rabin is stalling and disregarding aspects of the agreement that would solidify Palestinian statehood, like ending the total Palestinian economic dependency on Israel.” Also that “Arafat, who had put everything on the line for peace, was being treated with contempt.” In contrast with Sadat, who visited Jerusalem with great fanfare and was allowed to pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque, Arafat was never permitted to enter the city.

True to his nature, he read the fine print and found that the Oslo Accords were seriously flawed. On the occasion of his 70th birthday, he gave an interview with Ma’ariv that became the weekend cover story. The headline read, “Rabin Does Not Want Peace.” This statement permanently severed the relationship between Rabin and him, two introverted men of steel who for 30 years had fought side by side and worked together to build the Israeli army, and in 1967 led it to the final conquest of the “Promised Land.”

In another interview he gave to the daily Yedioth Ahronoth in late 1994, he said, “The Palestinians believed the Oslo Accords would lead to a Palestinian state, but Rabin had no intention of letting that happen.” Again in his dry, analytical style, he claimed “the Palestinians might be allowed to collect their own garbage and print their own passports, but this mini-state would ultimately be controlled by Israel.”

His last political article was titled “A Requiem to Oslo” and appeared in a magazine published by The Israel Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace. There he predicted the disastrous end to the peace process. He argued that the process had already reached an impasse from which it may not recover. “The failure was due, quite clearly,” he wrote, “to Rabin’s refusal to redeploy forces on the West Bank and allow general elections to be held in the Occupied Territories.”

He continued: The real cause for Israel’s position is that the results of general elections confirming Arafat as the unchallenged leader of the Palestinian people, would place the Palestinian side closest that they ever came to statehood status. This he said during the years that Rabin was receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and the world saw him as the man of peace. So, once again, he was saying the unthinkable.

Lets back up a little here

In contravention of international law, Israel had been building settlements on the lands occupied in 1967—the Sinai, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, and Gaza—and populating them with civilians. The reasons for this are numerous—from Messianic to security-related to the fact that it was a profitable enterprise for many businesses.

On the night of March 21, 1968. At the insistence of Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, a major Israeli army offensive took place in the village of Karame, east of the Jordan River. Fatah headquarters were located in the village, and Yasser Arafat was based there with a few hundred Palestinian fighters, or fedayeen. In what was the first open battle between the Jewish army and the Palestinians since 1948, Israel mobilized more than a hundred tanks, the entire 35th Airborne Brigade, Special Forces commando units, several air force squadrons, and an entire reservist infantry brigade. The massive Israeli forces were too cumbersome. The tanks got stuck in mud, delaying the attack and ruining any element of surprise.

Arafat, who was barely known to the world until then, was informed by Jordanian intelligence that a large-scale Israeli military attack on the town was underway. During the battle that ensued, the Palestinians suffered heavy losses but they held their ground, surprising the Israeli military with their audacity.

The Jordanian army, got involved in the fighting, supporting the Palestinians and defending its sovereign territory against the invading army. The United States was vehemently against the attack. The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Arthur Goldberg, said that actions such as this, on a scale so out of proportion, “are greatly to be deplored.”

The battle achieved mythic proportions in the Arab World and on December 13, 1968, Time Magazine did a story about Fatah, and Arafat’s face appeared on the cover, bringing his image to the world for the first time. The title on the cover was, “The Arab Commandos: Defiant New Force in the Middle East.”

In Arabic, karame means “dignity.” For Israel, the battle of Karame has become synonymous with humiliation.

Ariel Sharon, or Arik as he is known in Israel, was larger than life. He was a war hero. He fought in 1948, he headed Commando Unit 101,2 he fought in 1956 in the Sinai Campaign, and he proved to be a brilliant commander in the 1967 War. He seemed destined to be the IDF chief of staff, but in early 1973, it became clear that he would not get the job, and he was forced to resign. IDF chief of staff is as much a political appointment as it is a military post.

When the 1973 Mideast war broke out, the only war that was not initiated by Israel and where Israel was caught completely off guard, Sharon was immediately called back to the army. He commanded a reservist armored division and he saved the IDF from a humiliating defeat.

In 1979, after several years of negotiations, Israel signed a peace agreement with Egypt, and one aspect of the agreement called for Israel to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt and to dismantle the Israeli settlements that were built there. Sinai is an enchanted desert with endless sand dunes, magnificent mountains, and spectacular coral reefs along the Red Sea coast. It also has a few oil wells and the all-important access to the Suez Canal.

However, returning all of this did not seem to be as serious a problem for Israel as dismantling the settlements and relocating the Israelis that lived there. It was common knowledge that these settlements were built on occupied land, and that whoever chose to make a life there knew they were taking the risk of being evacuated one day. Still, a serious problem arose when it was time to evacuate the Israeli settlements that were built in the northern part of the Sinai, near the Israeli border.

When the time came for the evacuation, extremist Israeli militants took over the settlement of Yamit and refused to leave peacefully. Most of the women and children had already been relocated by then, and the army was sent in to get the extremists.

From an Israeli perspective, Egypt was the only Arab country that could possibly deter Israel militarily. Now that it was neutralized due to the peace agreement, Sharon saw an opportunity to decimate the Palestinian leadership, which at the time was in exile in Beirut, Lebanon, and place a pro-Israeli, Christian-dominated government in power in that country. I was home on weekend leave on that fateful June in 1982 when, not six months after the peace agreement with Egypt had been concluded, Israel began its heavy-handed invasion of Lebanon.

A great deal has been written about the massacres that took place in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila west of Beirut. It was September 1982, Sharon had a plan to “clean up” the Palestinian presence in Beirut and allow the pro-Israeli Lebanese Christian militia, the Phalangists, to take control. The Israeli army sealed the two camps and allowed the Phalangists to enter, illuminating the dark night with flares that lit up the sky. They killed indiscriminately for hours in full view and with the logistical support of the IDF top command.

Later on it became clear that young Israeli soldiers and officers who realized what was going on and tried to alert the chain of command were reassured that everything was under control. Arabs were killing Arabs, and it was not our problem. Sharon’s involvement in the massacres at Sabra and Shatila was his downfall. Massive protests in Israel and around the world resulted in a formal inquiry that found Sharon to bear personal responsibility for the carnage. He was forced to resign and was barred from ever heading the defense ministry. For the next 18 years, he was a political pariah.

Moving on to the post-Rabin era

Netanyahu was elected prime minister in 1996, sweeping into office after Yitzhak Rabin’s murder—capitalizing on the country’s total disillusionment with the Oslo peace process and a rash of suicide bombings, which Netanyahu promised to put a stop to. He had campaigned under the slogan, “Making a Safe Peace.” Things didn’t seem very safe or peaceful at the moment.

1999, Israel had elected Ehud Barak, who promised he would negotiate with the Palestinians and end the conflict once and for all. In the summer of 2000, Barak and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat met at Camp David in Maryland at the invitation of President Bill Clinton to finalize and seal a peace agreement. Arafat insisted it was premature to hold a summit, but his opinion was ignored and the summit was convened on July 11.

on July 25,…. President Clinton emerged from the summit and said, “The prime minister moved forward more from his initial position than Chairman Arafat.”This was a serious accusation coming from the guy who was supposed to be the “honest broker.” He was blaming Yasser Arafat for not being flexible enough. Barak said, “We tore the mask off of Arafat’s face,” and now we know that Arafat did not want peace after all.

Yasser Arafat had been consistent for years. For the sake of peace, he was willing to give up the dream of all Palestinians to return to their homes and their land in Palestine. He was willing to recognize Israel, the state that destroyed Palestine, took his people’s land, and turned them into a nation of refugees. He was ready to establish an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza—which make up only 22 percent of the Palestinian homeland—with Arab East Jerusalem as its capital. He was ready to do all this, but he was not going to settle for anything less. He had always been clear about what he saw as the terms for peace.

What the Israelis had demanded at Camp David was tantamount to total Palestinian surrender. It also became clear that Ehud Barak himself was despised by his own aides and that none of his political allies remained with him due to trust issues. Barak demanded that Arafat sign an agreement to end the conflict forever and in return, he would be permitted to establish a Palestinian state on an area of land that could not be defined clearly because it was broken into pockets with no geographic continuity. Instead of Arab East Jerusalem, he would receive a small suburb of East Jerusalem as his capital. To that, Yasser Arafat refused to agree.

September 2000, frustration and disappointment ran high and the atmosphere was charged when Ariel Sharon who was opposed to the peace process from the beginning decided to march to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. He did it surrounded by hundreds of fully armed police in riot gear. The Temple Mount, or Haram al Sharif as it’s known to the Muslim world, is a 35-acre plaza that takes up one-sixth of the Old City of Jerusalem. It is home to the Dome of the Rock, the most iconic structure in Jerusalem, and the Al Aqsa Mosque. This mosque is believed to sit on the spot where patriarch Abraham was going to sacrifice his son. It is believed to be the site of the First and Second Jewish Temples, and it is the place from which the prophet Mohammed made his night journey into the heavens. It is so holy for Jews, that observant Jews refrain from entering it for fear of defiling the Holy of Holies. For Muslims around the world, only Mecca and Medina are holier than Jerusalem.

Sharon claimed he was merely exercising his right to visit the place. It was more like an invasion than a visit. The response was immediate and entirely predictable. Palestinians from all walks of life saw this as desecration of holy ground, and massive protests began. Israel reacted with violent force. The unrest spiraled into ever-harsher Israeli repression and massive Israeli military incursions into the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinian-Israelis in northern Israel also protested, and they too were met with violent response from the police, who shot and killed 13 civilians. Sharon lit the fuse over this barrel of explosives, and thus the second Intifada or Uprising was born.

Barak was forced to call early elections. These were held in February 2001, and Barak suffered a humiliating defeat, making his period in office the shortest of any Israeli prime minister. Ariel Sharon, who ran against Barak, won in a landslide.

Near the end of the book the Generals Son learns something that if true might have had something to do with the Generals turn from Warrior to Peace Activist in 1967. Its rather long winded so I will edit for brevity

I later learned that Abu Ali was born in January 1939, so he was not yet 10 when this occurred. “He commanded the forces that defended our village, Beshshit,1 and was killed in the battle. After the battle, our village was destroyed and we ended up at Rafah Refugee Camp in the Gaza Strip. My father was killed in battle, but war is war; you expect that a man may be killed. But

In 1967, just days after the end of the Six-Day War, the Israelis massacred civilians in Gaza . An Israeli army officer showed up in a neighborhood at the Rafah Refugee Camp in Gaza, leading a company of soldiers and a bulldozer. The soldiers told everyone to come out of their homes. The officer inspected everyone and then sent the women and the children who were under 13 years old back home. He took all the men and the boys over 13 (more than 30 ) to another part of the camp, far enough so the families could not see. Then the soldiers lined everyone up against a wall and shot all of them. When they were done, the officer went one by one and shot each person in the head.” “

After he shot them, the bodies were laid in a row on the ground and the bulldozer began driving over them, going back and forth and back and forth until the bodies were unrecognizable.”

While interrogating a prisoner some time later an interrogator named Pinhas was told this story and reported it to an officer that worked with the General . General Peled then heard and he went to see for himself and visited the homes of the victims. He then wrote a report to Yitzhak Rabin and Haim Bar-Lev, but they did nothing.

The Generals Son recalls

“Immediately after the war, while still in uniform, my father said that Israel must recognize the rights of the Palestinian people. He said that if we don’t do this, the Israeli army would become an occupation army and would resort to brutal means to enforce the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian people. He said this while still in uniform, and he never stopped saying it and advocating for Palestinian rights till he died.” …..”If we keep these lands, popular resistance to the occupation is sure to arise, and Israel’s army would be used to quell that resistance, with disastrous and demoralizing results”

I will end this with 2 more quotes from the book

As the Hebrew poet Haim Nahman Bialik wrote, “Satan has not yet invented vengeance suitable for the blood of a young child.”

and

A story from the Old Testament, where Abraham the patriarch argued with God over His decision to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorra:

And Abraham stood before the Lord. And Abraham drew near, and said: wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked, perhaps there be fifty righteous within the city, wilt thou also destroy and not spare the place for the righteous that are therein? …and the Lord said, if I find in Sodom fifty just men within the city, then I will spare all the place for their sakes. (Genesis 18:23–26)

Surely there are 50 just men in Gaza

End