Bidens- FDA’s War on Babies, Yellen to Bail Out Crypto Wall Street Investors

And a Look Back at the Feds Last Bailout

Update 5/22

👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍👍

End Update

As Moms in America frantically look for baby milk powder to feed their infants the President seeks to give Ukrainian Nazis 40 billion and contemplates bailing out Crypto to prevent financial distress to the rich Wall Street Speculators

Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, a Democrat from Nevada, posed her question to Yellen as follows:

“Last week Fabio Panetta, one of the European Central Bank’s six Executive Board Members, noted that the crypto currency market is now larger than the subprime mortgage market which triggered the global financial crisis. Nobody knows that better than us in the state of Nevada.

“And he says this $1.3 trillion [crypto] market shows strikingly similar dynamics. There are about 10,000 crypto assets now. So my question Madam Secretary is: one financial risk posed by the crypto currency is the concentration of ownership. Do you see any financial risk because professional investors and high net worth individuals hold almost two-thirds of the Bitcoin supply?”

Yellen said there could be financial stability risks if those professional investors were leveraged to the point “that a decline in the value of the assets could trigger financial distress which spills over to others.” Yellen said that President Biden has asked the U.S. Treasury and F-SOC to look at the risks presented by crypto and they will be issuing a “comprehensive report” on this shortly.

The Baby Powder shortages are a perfect example of a Cartel controlling supply and pricing. Three companies control 98% of the market. Despite one of the cartels factories being closed for 3 months, somehow nobody took the opportunity to ramp up production at the remaining factories and supplementing domestic production with imports, and certainly Sleepy Joe never contemplated restricting exports

One excuse given is there is a 17.5% tariff on imports. Lol. How stupid do they think we are, this would have been passed onto the consumer and mfr could have marked up domestic production by at least that

Another excuse is infant formula is subject to onerous U.S. regulatory (“non‐ tariff”) barriers. For example, the FDA requires specific ingredients, labeling requirements, and mandates retailers wait at least 90 daysbefore marketing a new infant formula. Therefore, if U.S. retailers wantedto source more formula from established trading partners like Mexico or Canada, the needs of parents cannot be quickly met because of these wait times.

Give me a break, an Executive Order or emergency legislation takes care of that. But oh wait, Ukraine is more important, so too busy to do anything about feeding American babies.

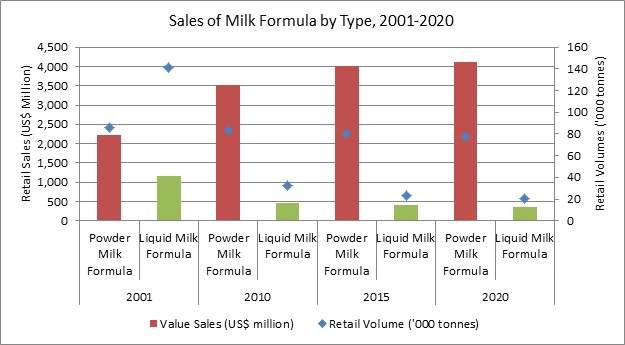

Now how about suspending exports?. Data is hard to come by but it seems we consume 35,000 tons of baby milk powder a quarter and export ~9,300 tons a quarter

Ramping up production? Abbot accounts for 42% of the market. Not sure how much that 1 closed factory makes up (much of it) but you would think the competitors would be able to ramp up that 58% .

As for the necessity of the closure I cant comment on that since I don’t know. But while its laudable FDA wants to protect babies from unsafe food even if they have to go hungry, its seems their concern does not apply to vaccines.

They are moving full speed ahead to get them vaccinated for a virus/disease that doesn’t affect them much. While not requiring the vaccine to be effective, and doing a shoddy job of ensuring these EXPERIMENTAL vaccines are safe while the manufacturers have immunity from liability.

If I didn’t know better it seems FDA really doesn’t like babies

Somebody, many bodies, should be locked up IMO.

https://www.cato.org/blog/rock-bye-trade-restrictions-baby-formula

For those interested:

Pffft

Anyways, I just finished this book.

It was quite informative. I wanted a closer look at what went on starting in 2019. Like many people I was caught up in the Virus and Lockdowns and the details of what the Fed was up to was not on my radar.

The book offers some clarity, although there is a bit of political bias here and there , but it doesn’t really affect what I present here. Since the Fed might be going into action again soon its worthy to review their actions from 2019-2021.

The one major flaw is the lack of any mention of Black Rock and their Going Direct proposal at Jackson Hole Wyoming in August 2019 and their appointment in March 2020 to select the assets the Fed would purchase. Thats a pretty big miss.

For more detail on that you may read this

In March, 2019 the Fed announced it would be keeping interest rates flat, and Powell acknowledged that the puzzling lack of inflation was a large reason. “I don’t feel we have convincingly achieved our two percent mandate in a symmetrical way,” he said. “It’s one of the major challenges of our time, to have downward pressure on inflation.”

In July, Powell led the Federal Reserve to something extraordinary. The bank would cut interest rates, even though the economy was growing. The unemployment rate was 3.7 percent, the lowest it had been in about fifty years, and wages had been rising.

When the Fed reversed quantitative easing, it drained more than $1 trillion of excess cash out of the banking system. Excess bank reserves—meaning the level of cash that banks kept in vaults inside the Fed—had been drawn down from about $2.7 trillion in 2014 to about $1.3 trillion in September 2019. This was still about 76,000 percent more excess bank reserves than existed in 2008. But the reduction was significant.

A repo loan was short-term. It always worked the same way: A borrower would hand over Treasury bills in exchange for cash. Then, the next day or the next week, the borrower would give back the cash in return for the Treasury bills, paying a very tiny fee for the transaction. The whole point of a repo loan was to be able to get cash when you needed it, in exchange for ultrasafe Treasury bonds. This was very important for Wall Street firms—they had hard assets like Treasury bills, which were worth a lot, and they needed ways to unlock that value in the form of cash to meet their overnight obligations.

Banks were more than happy to do this short-term loan because it was so safe; the banks held on to the Treasury bills as collateral so there really wasn’t any risk. If the borrower went belly-up, the bank could sell the Treasurys and recoup the total value of the loan.

On September 16 , Monday , Repo rates continued spiking. They would hit 5 percent that day.... The analysts in New York were trying to get a handle on why the rates were spiking.

On Tuesday morning... the price of a repo loan crossed 9.5 percent. This was the territory that caused financial meltdowns. That day, the Fed initiated an unprecedented intervention into repo markets, offering to pump $75 billion into the overnight markets. That was just the start of a long bailout, which would later come to include massive new rounds of quantitative easing. ....The money that the Fed unleashed was not a neutral force. It benefited some people and disadvantaged others.

On one side of the struggle were lenders like JPMorgan, who offered repo loans. On the other side of the struggle was someone who desperately needed a repo loan to stay in business. ....When the rate hit 9 percent, it meant that somebody out there was so terrified and desperate that they were willing to pay loan-shark rates of 8 percent to secure a totally collateralized overnight loan, which normally cost about 2 percent or less.

Before the financial crisis, the market was mostly used by banks. But the banks didn’t use repo loans as often now that they had so much cash. A new group of financial players stepped in and started using repos: hedge funds. The amount of overnight repo loans used by nonbank actors like hedge funds roughly doubled between 2008 and 2019, rising from about $1 trillion to $2 trillion.

This figure, $2 trillion, understated just how important the repo market had become to hedge funds. Hedge funds used repo loans as the cornerstone to build a much larger structure of debt. They got cash from a repo loan, then used that cash as the payment to make a larger bet in the marketplace...... The hedge funds used $2 trillion in overnight repo loans to build positions in the market that were much, much larger than the repo loans themselves.

What were they [Fed] funding? And how risky were their activities? This remained a mystery because the hedge funds weren’t regulated as tightly as banks. They were part of a shadow banking system that didn’t face as much scrutiny from the FDIC and all the Dodd-Frank rules.

Even months after the repo market collapsed in 2019, the Treasury Department wasn’t entirely sure what the hedge funds had been up to.

The hedge funds had been piling into a very particular trade called a “basis risk” trade. The tactic was made possible by the very market tranquility that the Fed had manufactured over the years. The basis trade worked well only in an environment of enforced tranquility, where traders knew that the Fed would step in and stop any violent market turmoil. When this condition was met, hedge funds felt justified in borrowing hundreds of billions of dollars to build a trade that was virtually risk-free as long as market volatility was dead. The design was simple.

A hedge-fund trader searched out a small wrinkle in financial markets that almost always occurred naturally. The wrinkle was the very minute difference in the price between a Treasury bill and a futures contract on that Treasury bill.III This difference in price between the Treasury bill you buy today and the price of a Treasury futures contract is called the basis.

The hedge fund exploits the very tiny basis by purchasing a lot of the Treasury bills along with the futures contracts on the bills. The hedge fund then just holds on to the bills, and delivers them on the date they’re due, collecting a profit that is the basis price difference.

This is where the repo market comes in. The profit margin on a basis trade was essentially guaranteed, but it’s small. To make the trade pay off, a hedge fund needs to make the trade thousands of times over. They used the repo market to pull this off. The hedge fund takes the Treasury bill, uses it as collateral, and gets the cash needed to load up on Treasury futures contracts.

The hedge funds were able to lever up their bets by a factor of fifty to one, meaning every dollar they had allowed them to borrow fifty more dollars to use for trading.Ultimately, the hedge funds built a mutually reinforced tripod of debt and risk between Treasury bills, repo loans, and Treasury futures.

Between 2014 and 2019, the total value of “short” positions in the Treasury futures markets owned by hedge funds rose from about $200 billion to nearly $900 billion. This position was key to making the basis trade work.

If the price of repo loans rose, it instantly demolished the profitability of the basis trade. The hedge funds found themselves obligated to make payments on their futures contracts but had to pay more money to keep the repo debt rolling.

When repo rates spiked in mid-September, financial analysts on Wall Street started hearing alarming stories. Certain hedge funds were very, very desperate to raise cash and raise it quickly....If the repo market was closed off to hedge funds, then they would be forced to liquidate Treasury bills and mortgage securities at a level that was twice as large as the amount liquidated in 2008.

When the Fed entered the repo market on September 17, it bailed out any hedge funds that found themselves desperate for a repo loan. The going rate for such a loan was over 9 percent that day. The Fed offered such loans at 2.1 percent, using money it could create instantaneously.

Powell traveled to Denver to speak at an economics conference. He took the chance, during his speech, to announce what the Fed was about to do. “At some point, we will begin increasing our securities holdings to maintain an appropriate level of reserves. That time is now upon us,” Powell said. “I want to emphasize that growth of our balance sheet for reserve management purposes should, in no way, be confused with the large-scale asset purchase programs that we deployed after the financial crisis.”

Powell was saying that the Fed was going to do something that appeared to be quantitative easing but was not, in fact, quantitative easing. The key difference seemed to be the Fed’s intent. The Fed wasn’t pumping money into bank reserve accounts to stimulate the economy this time. It was just doing it to keep reserve levels high, for maintenance.

About a week later, the Fed announced it would buy about $60 billion worth of Treasury bills per month. Between September 2019 and February 2020, the Fed created about 413 billion new dollars in the banking system, judging by the increase of its balance sheet.

This was one of the largest financial interventions of any kind in many years. The traders on Wall Street nicknamed the new program NQE, short for “non-QE.”

The deployment of overnight repo loans showed that the Fed would not tolerate dangerous flare-ups in that market. The hedge funds acted on this insight, borrowing more money and using it to buy shares of stock.

A Goldman Sachs index showed that debt-fueled hedge-fund trades rose sharply after the repo bailout and the dawn of NQE. In February 2020 alone, the leverage ratio of hedge funds (meaning their debt compared to assets) rose by 5 percent, the biggest increase in years.

On January 13, 2020, the Dow Jones Industrial Average broke above 29,000 points, marking a record high.

In early 2020, the economy looked fine from the outsidethanks to the dazzling effects of cheap debt, rising asset prices, and a reach for yield that propped up risky investments like corporate junk bonds.

It was true that the unemployment rate was at the lowest level in decades, at an astoundingly small 3.5 percent. But the job boom was just only starting to nudge higher after many years of stagnating.

The real prosperity was being enjoyed at the highest peaks of the economic system by the people who owned most of the assets. When hedge funds borrowed money and plowed it into the stock market, the daily reports on cable news seemed quite cheerful: “The Dow closed at a record high today…” Who could complain?

Corona

In September, when the repo market had collapsed, the Fed shocked markets by offering $75 billion in repo loans. On Thursday, March 12, the Fed announced that it would offer $500 billion in repo loans, and would offer $1 trillion in repo loans the following day.

The Fed was offering $1.5 trillion in immediate assistance to Wall Street. It did virtually nothing to help. The Dow continued to plunge and closed the day down 2,300 points, or 10 percent.

Congress had limited the Fed’s emergency powers after the crash of 2008, when the Fed extended loans that were arranged quickly and with little oversight. When Congress passed the Dodd-Frank reform law of 2010, it included new restrictions on the Fed that required the bank to get approval from the U.S. Department of the Treasury for emergency actions that were not spelled out in the Fed’s charter.

When Congress created the Fed in 1913, lawmakers were cautious in defining the scope of the central bank’s powers. They were just as careful in setting strict limits on what the bank could not do as they were in defining what it could do. The Fed was denied the power to lend directly to corporations, or to take on risky debt like leveraged loans.

This was designed in part so the Fed could not pick winners and losers in the economy by directly subsidizing some industries over others. The Fed arguably went outside this stricture in 2008, when it arranged loans for failing investment firms like Bear Stearns. But Dodd-Frank gave the Treasury secretary clear oversight over such actions.

The Fed decided to resurrect a certain legal tool that it pioneered during the 2008 financial crisis, called a special-purpose vehicle, or SPV. An SPV was basically a shell company that allowed the Fed to get around the limits placed on its lending authority, using the U.S. Department of the Treasury as a partner.

Each SPV was basically a company, formed jointly between the Fed and the Treasury Department. The company was registered in the state of Delaware, at a cost of about ten dollars. The Treasury Department would invest taxpayer cash in each SPV, and then the Fed would use that cash as seed money to start making loans, lending as much as ten dollars for every dollar invested by the Treasury.

This taxpayer money is what allowed the Fed to go outside its usual limits and start buying risky debt and extending loans to new parts of the economy. If there were any losses, the losses would be paid for first by the taxpayers, which helped the Fed make the legal argument that it was not, in fact, making risky loans.

The Fed created three important SPVs by the end of that weekend.

The first two SPVs would allow the Fed to buy corporate debt. The motivation behind this was obvious. The Fed saw what was coming in the chain of failures as corporations defaulted on their loans, damaging the banks and hollowing out the value of CLOs. To prevent this calamity, the Fed expanded the Fed Put into an entirely new area of finance.

People who traded stocks now assumed that the Fed would step in with a rescue package if the stock market ever crashed. Now people who traded corporate bonds and leveraged loans would have the same assurance.

Now that the Fed had stepped in and become a major buyer of corporate debt, providing a floor for the market, it changed the very nature of interest rates on the debt. Those rates didn’t just reflect the risk of the company, but also reflected the Fed’s appetite to buy the bond.

Perhaps the most ground-breaking SPV was the third one, which would buy debt of midsize businesses that were too small to get leveraged loans or corporate bonds. ....The guiding principle of the program was that it would move the Fed’s reach beyond the confines of Wall Street. Instead of using the primary dealers to implement this plan, the Fed would use regional banks as its conduit. The banks would give loans to small business, and the Fed would buy 95 percent of the loan, letting the regional bank hold the remainder. The Fed called this program the Main Street Lending Program.

The Main Street program was unwieldy, complicated, and difficult to use. It relied on local and regional banks to first make loans to small businesses, which the Fed would then buy. But the Fed also insisted that the local banks keep 5 percent of the loan value, meaning the banks had to absorb some risk.

The banks were also deterred by the expense and work entailed with making loans to so many companies that might be in dire straits, with little chance of survival.

The Main Street program had been built to purchase as much as $600 billion in loans. It had purchased a little more than $17 billion in loans by December, the month that it was shut down.

The final piece of the rescue plan was not a new SPV, but a massive influx of money in the form of a large-scale, near-permanent quantitative easing program. The parameters of this new round of QE would be left intentionally vague. The Fed would create as much money as it decided was necessary, for as long as it was needed. The scale was unprecedented. In one week, the Fed bought $625 billion in bonds.

By Sunday evening, March 22, the plan was largely pulled together. But there was one small problem. The plan called for the Treasury Department to invest about $454 billion into the new SPVs, which would enable the Fed to loan about $4 trillion in new debt. But Congress had not yet passed a relief bill that would authorize the use of $454 billion of taxpayer money.

Powell and his team decided they would not wait on Congress. They would announce the new SPVs on Monday morning, March 23, before the markets opened.

In roughly ninety days, the Fed would create $3 trillion. That was as much money as the Fed would have printed in roughly three hundred years at its normal pace, before the 2008 financial crisis.

Within less than three weeks of its first rescue package, the Fed announced new actions that built on what it had already done. Once again, the plan was not voted upon by the full FOMC, and there are no transcripts available to determine the thinking behind the new initiatives, parts of which were approved by a unanimous, closed-door vote on April 8.

The Fed announced on April 9 that it wouldn’t only buy corporate bonds—it would also buy even riskier bonds, which were rated as junk debt. The junk bond purchases would not be unlimited. The Fed would only buy debt that had been rated as investment-grade before the pandemic. These bonds were called fallen angels on Wall Street, and they included debt from companies like Ford Motor Co.

Also that day, the Fed updated a separate new program (called TALF, for “term asset-backed-securities loan facility”) so that it could directly purchase, for the first time, big chunks of CLO debt, which was composed of leveraged loans. This was a significant extension of the Fed’s safety net, and it played a large role in quelling the anxiety around the hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of CLOs that faced loan write-downs and breaches of their standard caps. It also helped the big banks that owned billions in CLO debt.

There was the way things worked before the SPVs were created, and the way things worked afterward. “Fundamentally we have now socialized credit risk. And we have forever changed the nature of how our economy functions,” said Scott Minerd, the Fed advisor and senior trader at Guggenheim Investments. “The Fed has made it clear that prudent investing will not be tolerated.”

But just days after the Fed’s groundbreaking SPVs were announced, Congress would step into the breach. It would pass one of the largest, most expensive bills in modern history, called the CARES Act.

This was the chance for Mnuchin, Trump, Pelosi, and McConnell to show that they could solve big problems, and that the U.S. government could lend a hand when it was needed. The CARES Act authorized $2 trillion in spending to counteract the pandemic, including $454 billion in taxpayer money to fund the Fed’s SPVs.

The part of the CARES Act that got the most attention was the roughly $292 billion chunk of the spending that went directly to people. There was good reason for this spending to get the attention that it did. The impact was immediate and beneficial for the millions of people who received it. And the government had never truly done something like this before, sending direct payments to people regardless of their previous level of tax payments, or even of their current level of need.

These direct benefits were coupled with more benefits for those who had been directly affected by the lockdowns. Unemployment insurance benefits, administered by the states, were boosted by $600 a week through July. That benefit was partially extended that summer, although at a lower level.

The spending that went straight into people’s bank accounts was the most visible part of the CARES Act. But it was a relatively small part of the overall relief spending approved by Congress, which included the CARES Act and three smaller bills.Over half of all that money was aimed at businesses, according to an analysis by The Washington Post based on data from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

The largest chunk of the money, totaling $670 billion, funded an emergency loan program called the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP. The idea was that the businesses would get a PPP loan, keep their employees, and then the loan would be forgiven when the businesses reopened and everyone went back to work.....more than half of all the PPP money went to just 5 percent of the companies that received the loans.

Fully 25 percent of all the PPP went to 1 percent of the companies. These were the big law firms and national food chains, which got the maximum PPP amount of $10 million.

An analysis by the Federal Reserve and others found that the PPP program saved about 2.3 million jobs at a cost of $286,000 per job, after President Trump claimed it would save or support 50 million jobs.

About $651 billion of the CARES Act was in the form of tax breaks for businesses, which were often complicated to obtain. This meant that the tax benefits went largely to the big companies that could hire the best tax lawyers.

About $250 billion of the tax breaks were given to any business in any industry, without regard to how much they might have been hurt by the pandemic. People who owned businesses were given tax breaks worth $135 billion, meaning that about 43,000 people who earned more than $1 million a year each got a benefit worth $1.6 million. By and large, these billions of dollars were quietly absorbed into corporate treasuries and personal bank accounts around the country.

The wildly unequal distribution of the money was not made public until months later, after The Washington Post won an open-records lawsuit that made the information public.

The real bailout, the successful bailout, was shockingly strong and swift. This was the bailout for people who owned assets. The owners of stock were made entirely whole within about nine months of the pandemic crash. So were the owners of corporate debt.

Starting in March, when the Fed intervened, the stock market began one of the largest, fastest booms in its history, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average exploding in value. The market hit its low point in mid-March, when the Treasury market collapsed. But between that day and the middle of June—in just three months—the market’s value surged by 35 percent.

Millions of people were out of work, millions more were in constant danger of being evicted, restaurants were shuttered, and hundreds of thousands of people were dying. But the debt and equity markets were on fire.

On December 16, Powell made a big announcement. Some of the most important emergency measures the Fed had deployed during the spring would now be made semipermanent.

While the Main Street Lending Program was sputtering to a quiet end, other parts of the bailout would endure. The Fed would keep interest rates at zero, and would now conduct $120 billion in quantitative easing every month for the foreseeable future.

That was about a decade’s worth of money creation, at historic rates, conducted every thirty days.

Powell said the Fed would continue to intervene as long as price inflation didn’t rise above 2 percent for an extended period of time, an eventuality that he said was unlikely in the near future.The price of certain items had spiked because of supply disruptions, but weak growth and weak demand were smothering prices overall. Asset price inflation, however, was accelerating without restraint.

By the end of 2020, companies issued more than $1.9 trillion in new corporate debt, beating the previous record that was set in 2017. Business for leveraged loans and CLOs was booming. American companies would carry this debt for many years to come because of the way it was structured. Companies had to either roll the debt by selling it again, or pay it in full when the loan expired.

The corporate debt binge brought a new and troubling term into corporate America’s lexicon, something called the “zombie company.” A zombie company was a firm that carried so much debt that its profits weren’t enough to cover its loan costs. The only thing that kept zombie companies out of bankruptcy was the ability to roll their debt perpetually.

During 2020, nearly two hundred major publicly traded companies entered the ranks of the zombie army, according to an analysis by Bloomberg News. These weren’t just marginal or risky firms, but included well-known firms like Boeing, ExxonMobil, Macy’s, and Delta Airlines. When Bloomberg analyzed three thousand large, publicly traded firms, it found that about 20 percent of them were zombies.

By March 2021 The Fed was pumping $80 billion a month onto the safe side of the seesaw by purchasing Treasury bills, which in turn depressed the interest rates, or yield, on those bills. As had been happening for a decade, this forced investors to push their money to the risky side, seeking yield.

Something worrisome started to happen in March, 2021. Treasury interest rates had started to climb, regardless of the Fed’s intervention.

President Trump and the Republicans in Congress had passed a tax cut in 2017 that forced the government to borrow $1 trillion every year to keep the government running, even when the economy was at its peak in 2019.

When the pandemic hit, Congress approved more than $2 trillion in spending in the CARES Act alone, all of it financed by deficit spending. In March, President Biden signed a new $1.9 trillion rescue package.

All of this meant that the U.S. Treasury would be selling about $2.8 trillion in Treasury bills during 2021.The Journal article documented the troubling fact that there might not be enough demand for all that debt to keep Treasury interest rates down at the low levels where the Fed had been pushing them.

If Treasury rates rose, all that investment cash on Wall Street would be enticed to move toward the safe end of the seesaw, finding shelter in the higher, safer yields that had been denied for so long.

This would drain cash out of the markets for leveraged loans, stocks, CLOs, and all the risky structures that Wall Street had been busily building for many years. Powell and his team would then face a familiar choice. They could let the risky structures fall, or intervene once again with more quantitative easing and emergency programs.

The entire bottom half of the U.S. population owned about 2 percent of all the nation’s assets. The top 1 percent of the population owned 31 percent. This helped explain why the households in the very middle of America’s income scale—meaning the middle 20 percent—saw their median net worth rise by only 4 percent between 1989 and 2016.

During the same period, the net worth of people in the top 20 percent more than doubled. The wealth of the top 1 percent nearly tripled. Millions of people in the middle class were falling behind. To compensate for this fact they took on loads of cheap debt, which helped them feel like they were at least remaining in place.

Consumer debt hit $14 trillion in late 2019, a record level even after adjusting for inflation. The only good news seemed to be that interest rates on the debt were lower.

[Guess what happens when interest rates rise to fight inflation caused by market manipulation, supply side disruptions and engineered shortages to drive up inflation?]