After the Revolution, Russias Civil War, Polish War, Peasant Wars, Church Wars and Famine give birth to the Soviet Union in 1922

During all that chaos was spawned Ukrainian Nationalism and a first wave of emigration to the West which would be followed by a greater wave following World War II known as the Galician Diaspora, some of whom would become implicated in JFK assassination (but thats or another Part)

1917-From wikipedia

In late March a group of intellectuals led by Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi formed the Ukrains’ka Tsen- tral’na Rada (Ukrainian Central Council). Its initial, modest objectives were to coordinate the national movement and to demand from the Provisional Government the right to print books and newspapers in Ukrainian and to teach it in schools.

By April the Rada’s demands had grown: they wanted national autonomy within a federation of Russian republics, and summoned an All-Ukrainian National Congress to discuss it. Conferences and congresses followed, as new Ukrainian newspapers and political parties emerged. A numerically small group of Ukrainian liberal intellectuals in Kiev dominated most of this activity.

Although the Rada was reformist in its social policies – and included in its membership Social Democrats such as the writer and intellectual Volodymyr Vynnychenko – it was at this point only a government-in-waiting. It had little support and still believed in a federal solution via a Constituent Assembly.

The Rada had few supporters in the villages, and peasants were indifferent to the nationalists and their organisations, understanding that the Rada’s objective was to replace the Russian and foreign bourgeoisie with a more liberal Ukrainian one. ‘Get off the rostrum! We’ll have nothing to do with your government!’ they shouted at one unfortunate nationalist who tried to arouse their feelings against the katsapy in Guliaipole.

Rada made a unilateral declaration of Ukrainian autonomy in June 1917

After the Bolshevik Revolution the divided Ukrainian Bolsheviks did not follow the Russian example and come to power in Kiev. In some places – in Lugansk and other towns of the Donbass – they did gain control and refused to recognise the Rada. In other areas, including Khar’kov and Ekaterinoslav, they collaborated in piecemeal fashion with both Ukrainian and Russian left parties and did acknowledge the Rada.

Relations between the Rada and the Bolsheviks in Kiev were hostile, but despite this, the Bolsheviks briefly joined the so-called ‘Small Rada’, a committee that sat in continuous session and made important decisions when the full Rada was in recess.

However, the launch of a White counterrevolution in the southeast complicated this struggle between the Bolsheviks and the Rada. The day after the Bolsheviks took over in Petrograd, Alexei Kaledin, a Cossack general, declared an independent Don Cossack state.

In December 1917, Lenin assigned Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko to the task of crushing the revolt, and by January the Bolsheviks were at war with the nationalists of the Rada as well. The Russian-Ukraine Civil War was on

The Ukrainian republic that emerged in 1917 sued the Central Powers for peace in February 1918, ending the state of war – and reducing the country to a mere ‘nation-building project approved by the Germans’. The German army moved into Ukraine on 18 February, and quickly drove the Bolsheviks out.

By 1 March they had occupied Kiev and reinstated the Rada. The Austrians – latecomers who needed food supplies more than the Germans – insisted on control of specific areas, such as the port city of Odessa. The army commands eventually agreed on a demarcation of zones of influence on 28 March, with Germany allotted the lion’s share of territory.

Austria gained control of half of Volhynia, Podolia, Kherson and Makhno’s province of Ekaterinoslav,although it was the Germans who controlled the collection and distribution of resources.

In March, the Bolshevik government in Moscow signed a peace treaty withdrawing Russia from the war. Survival depended on ending the fighting, but the price was high. Russia lost Finland, Poland, the Baltic countries, Bessarabia – and Ukraine was already gone.

Although resources provided to Germany and Austria were denied to Russia, Lenin and Trotsky nonetheless needed to secure a workable peace with the Central Powers.

The Rada succeeded in isolating Ukraine from Bolshevik rule, but at the price of exposing the population to military occupation.Indeed its power ‘rested chiefly on German bayonets’.

On 15 March the Rada asked the Germans to ‘liberate’ eastern Ukraine – the provinces of Khar’kov, Ekaterino- slav, Tauride, Poltava and Kherson, which were still under Bolshevik control. The Germans seized their chance and pushed on towards the Black Sea coast and the Donbas, meeting with only sporadic resistance from Red Guards.

Even in these chaotic conditions, by the end of April Ukraine was fully under foreign military occupation and was forced to supply the Central Powers with the huge quantities of grain, animals and poultry that they demanded.

The Germans were losing patience with the Rada: on 24 April a senior official wrote that ‘... cooperation with the current government ... is impos- sible ... The Ukrainian government must not interfere with the military and economic activities of the German authorities ...’There followed a list of demands that the Rada would clearly never accept.

On 26 April General Hermann von Eichhorn, placed Kiev under martial law, and two days later Pavlo Skoropadskii was proclaimed Hetman of Ukraine, reviving an eighteenth-century military title. Skoropadskii – a wealthy, con- servative officer – consented to German demands: to recognise Brest-Litovsk; to form a Ukrainian puppet army; to dissolve the soviets and land committees; to adopt legislation on the compulsory delivery of grain; and to sign a free- trade agreement with Germany. He agreed to restore property rights, permit private ownership of land, and preserve the large estates ‘in the interests of agri- culture’.

The Hetmanate relied upon the professional administrators of the old Tsarist state apparatus: its police force, the Dershavna Warta or State Guards, were noted for their brutality. General Erich Ludendorff commented that ‘we [had] found a man with whom it was very easy to get along’, and German officials began planning a puppet Ukraine modelled on British dominions, with a government of dependable local notables.

In June 1918 Bolshevik fortunes were at a low ebb. The Reds were threatened by the Germans in the west and the south, the Whites in the Caucasus and the Czech Legion and the Whites across the Urals.

The Mensheviks and Right SRs had been expelled from VTsIK on 14 June, primarily because of their involvement in the so-called ‘democratic counter-revolution’. The Bolsheviks lacked an effective army and were running short of food. The railway workers in Moscow were restless, and on 19 June shooting broke out at a union meeting. A split with the Left SRs over the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was imminent.

By the autumn of 1918 the Central Powers were losing the war on the Western Front, and their grip on Ukraine loosened. In October the Austro-Hungarians left Guliaipole, and the insurgents marched in.

In late December the Red Army,under the command of Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, began to advance into Ukraine from the north.

On 4 January, 1919 the Revolutionary Military Council (Revoliutsionnyi Voennyi Sovet or RVS) unilaterally took the important military decision to constitute a Ukrainian Front, with Soviet forces having already captured Khar’kov the day before over ineffectual protests from the Directory in Kiev.

On 16 January Petliura mounted a coup to gain control of the Directory, and, ignoring earlier diplomatic feelers to Moscow and under pressure from his French sponsors, declared war on Soviet Russia.

By this time Denikin’s Volunteer Army consisted of over 80,000 men, of whom perhaps 30,000 were tied down in the rear, protecting his communication and supply lines from partisan raids.

So lets take a look at the goings on from 1919-1922. Taken from the Russian Revolution by Sean McMeeken

https://www.amazon.com/Russian-Revolution-New-History/dp/0465039901

Cut off from major European suppliers by the Allied blockade, for most of 1919 the Bolsheviks were reduced to haggling with small-time smugglers and con men.

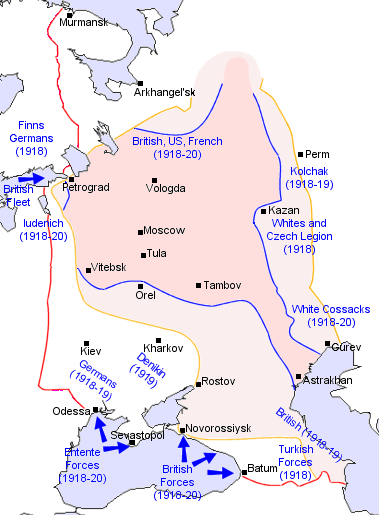

In addition to the British fleet patrolling the Baltic, the lands of the former tsarist empire were now occupied by foreign troops—Czechoslovak, British, French, American, Japanese—who offered the regime a scapegoat for the privations ordinary Russians were enduring. In political terms, it is not always a bad thing for a government when its people suffer hardship in wartime, when shared sacrifices can bring people together against a common enemy.

Emblematic of the social logic of War Communism was the introduction, on October 31, 1918, of “universal labor duty,” which was soon expanded to include subbotniks (compulsory weekend work battalions). Private labor unions were then abolished, which effectively eliminated the right to strike.

As Trotsky, turning Marx’s idea about the “emancipation of labor” on its head, explained the imperatives of War Communism, “As a general rule, man strives to avoid work… the only way to attract the labor power necessary for economic tasks is to introduce compulsory labor service.”

Surrounded by domestic and foreign enemies, with her put-upon workers and peasants conscripted into either the Red Army or universal labor duty, Lenin’s Russia was mobilized for war

Trotsky had already begun enlisting tsarist officers in the Red Army in spring 1918, but only about eight thousand had signed up so far; Lenin’s proposed army would require ten times that many.

Moreover, many of Trotsky’s early officer recruits had enlisted in the hope of fighting the Germans (then carving up Ukraine, White Russia, the Baltics, and Finland)—only to discover, by fall 1918, that their most likely opponents would be either Russia’s former allies, or worse, their fellow tsarist officers in the Volunteer Army.

Even so, the German collapse made Trotsky’s task, in political terms, a bit easier. In spring and summer 1918, the Allied landings at Murmansk, Vladivostok, and Archangel had been small-scale and, in theory at least, friendly.

In Ukraine, the situation was fluid. The Germans were withdrawing very slowly (concerned about Bolshevik penetration, the Allied Supreme Command had stipulated in the November 1918 armistice that German troops should leave only “as soon as the Allies shall think the moment suitable, having regard to the internal situation”

The western Allies, pursuant to the Mudros armistice they signed with Turkey on October 30, now controlled the Black Sea, which enabled a British-French landing at Novorossiisk, in the Kuban area in the rear of the Volunteer Army, on November 23.

The Volunteer Army itself was entrenched in the north Caucasus, under protection of the Kuban Cossacks, but General Denikin’s cool relations with the Don Cossack ataman, General Krasnov, complicated any advance farther north.

Britain and France did control Russia’s Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangel, with more troops (including 5,000 Americans) landing there all the time. Still, Archangel was 770 miles from Moscow along a jerry-built railway very easy to sabotage, and Murmansk another 500 miles farther still.

In Siberia, there were 70,000 Japanese and 7,000 American troops on the ground. But most of them were stationed in the Far East between Vladivostok and Harbin, 5,000 miles from Moscow.

Despite laboring under material disadvantages, both Denikin and Kolchak put together real armies during the winter lull in fighting between November 1918 and March 1919. The departure of the Germans from the Don basin helped, by costing the Don Cossacks their patron and forcing their ataman Krasnov into an alliance of convenience with Denikin.

On January 8, 1919, Krasnov accepted Denikin’s command, instantly enlarging the Volunteer Army by 38,000 men. By mid-February 1919, Denikin’s “Southern Army Group” counted 117,000 men, 460 guns, and 2,040 machine guns.

The departure of the Germans from Ukraine and the collapse of their puppet Hetmanate in Kiev (replaced by a short-lived “Ukrainian People’s Republic”) opened up a new front for operations for Denikin, who could now outflank the Reds to the west and maybe even link up with the Polish army forming, led by Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, under Allied auspices.

While this was bad news for the 30 million people of Ukraine, whose second dawn of independence would last less than two months, it was good news for the Whites.

On paper, Kolchak’s Army in East Russia was even stronger than the Volunteers. By February 1919, Kolchak had 143,000 men under his command, enough to outnumber the Red Eastern Army Group, which counted only 117,600 (although the Reds had another 150,000 or so in reserve east of Moscow, in case of a White breakthrough).

The Red Eastern Army Group was superior in both artillery (372 guns to 256) and machine guns (1,471 to 1,235), but owing to British aid, the Whites had enough stocks to sustain an offensive, if not indefinitely.

Trotsky’s heightened focus on the eastern front did open up room for Denikin in the south. In mid-June 1919, just as the Siberian Army was falling back to the Urals, the Volunteers advanced into the Donbass region. Kharkov fell on June 21, opening up the path through central Ukraine to Kiev.

On Denikin’s right flank, a Caucasian Army, commanded by Baron P. N. Wrangel, a highly decorated cavalry officer of Baltic German stock, crossed the Kalmyk steppe and closed on Tsaritsyn, where the Reds had spent all winter digging trenches and erecting barbed wire. Deploying two British tanks, Wrangel’s army breached these defenses and crashed into Tsaritsyn on June 30, capturing some forty thousand Red prisoners.

Wrangel’s was a signature victory in the Civil War. Timing did not favor the Whites, however. Far from coordinating his advance with Kolchak—a virtual impossibility, owing to the lack of a direct telegraph connection—Denikin’s Volunteers had reached the Volga at Tsaritsyn at a time when Kolchak’s forces were retreating all across the line, their own high water mark, less than 50 miles from the Volga east of Saratov, having been reached nearly two months earlier.

It was a similar story in Ukraine, where France’s own limited intervention had petered out long before Denikin finally went on the offensive in June. Because France had sustained such terrible losses on the western front, the sixty-five-thousand-odd “French” expeditionary force, which was commanded by Franchet d’Espèrey, and had landed at Odessa and on the Crimean Peninsula in December 1918, consisted mostly of Greek, Romanian, and French colonial troops from Senegal, none of whom had shown much enthusiasm for fighting in Russia’s Civil War.

In the first week of April 1919, a disgusted Franchet d’Espèrey simply evacuated the lot of them, along with forty thousand “White” civilians, including Grand Duke Nicholas—the first of many waves of Russian émigrés to leave via the Black Sea and Constantinople (where there was soon a large Russian colony, the glamorous women of whom titillated Muslim men not accustomed to seeing unveiled women in public).

The French withdrawal from Crimea was hardly an encouraging omen for the Volunteer Army as it poured into Ukraine. The Allied Supreme Command in Paris had some hope that Pilsudski’s new Polish army might put pressure on the Red Army from the West. The Poles indeed fought a series of small border engagements with the Red Army in spring and summer 1919 in Lithuania and White Russia.

But for Polish nationalists to cooperate with Denikin’s Volunteer Army of Russian patriots and Cossacks would require something of a political miracle.

In Lithuania and White Russia, the Reds moved into Vilnius and Minsk after the German withdrawal in early 1919, only to lose these cities to Pilsudski’s Polish army in April and August 1919, respectively.

Although willing to parley with both Lenin and Denikin, Pilsudski had concluded, by September 1919, that it was “a lesser evil to help Soviet Russia defeat Denikin,” and so he decided not to engage the Reds during Denikin’s fall offensives. Pilsudski secretly informed Moscow of his decision in early October, which allowed Trotsky to transfer forty-three thousand troops south to face Denikin.

In the absence of diversionary help from the French, Poles, Estonians, or Finns, and with Kolchak’s Siberian army reeling, Denikin’s Volunteers would have to fight on their own as they slogged their way north.

As Denikin’s armies marched into the heart of Ukraine, the Russian Civil War approached its sinister climax. The Volunteers quickly captured Red-held territory. But Denikin’s supply lines were soon stretched to the breaking point, and they were thinly guarded.

Ukrainian peasants were no more well disposed to the Whites than they had been to the German occupiers or the Reds, who had set grain requisition quotas even higher than the Germans had.

The posture of most Ukrainian peasants was “a pox on all your houses,” with farmers hiding their produce underground to deny them to marauding armies.

By the time the Whites moved in, there were a half-dozen partisan armies operating in Ukraine, ranging from right-populists led by the Cossack hetman Semen Petliura to the far-left anarchists led by Nestor Makhno, a kind of T. E. Lawrence of the Russian Revolution, who blew up troop trains and robbed the survivors.

Given an army commission by Trotsky in December 1918, Makhno had turned against the Reds. On August 1, 1919, Makhno issued his own Order No. 1, which called for the extermination of the White Russian “bourgeoisie” and of Red commissars.

The one thing Ukrainian partisans had in common was xenophobia, encompassed in slogans like “Ukraine for Ukrainians” and “Ukraine without Moscovites or Jews.” Long before the Whites had moved in, pogroms had erupted in the old Pale of Settlement on both sides of the shifting military lines.

The Terek Cossacks, notorious Jew-haters, reached western Ukraine in October 1919 and crashed into Kiev, Poltava, and Chernigov. In a single pogrom in Fastov, outside of Kiev, 1,500 Jews were slaughtered, including 100 who were reportedly burned alive.

Denikin, concerned about the erosion of discipline, condemned such atrocities and even tried, on several occasions, to convene courts-martial. Still, the evidence is abundantly clear that thousands of his troops, including regulars, officers, and Cossacks, indulged in terrible pogroms.

As ugly as the situation was in Denikin’s rear, the vistas opening up in front of him seemed endless. On August 10, a flying brigade of eight thousand Cossack cavalrymen, led by General K. K. Mamontov, captured Tambov and Voronezh, inducing panic in Moscow.

On September 12, Denikin ordered all his armies, “from the Volga to the Romanian border,” on the offensive, with Moscow the objective. Kursk fell on September 20, and there were signs of collapsing Red morale, with some units deserting en masse to the Whites.

On October 13–14, the Volunteer Army conquered Orel, only 250 miles from Moscow, and less than half that distance from Tula and its munitions factories. Meanwhile in Pskov, Yudenich had launched his own assault on Petrograd on October 12, not so much in coordination with the Volunteers as in defiance of the British, who had demanded, on October 6, that he transfer his forces to Denikin’s front.

The British did contribute six tanks, along with their British crews, to NW Army, along with naval support. Other than this, Yudenich’s NW Army, now seventeen thousand strong, was on its own: Laidoner’s Estonians refused to fight. The British tanks were rendered useless after the Reds blew up the bridge over the Luga River. Nonetheless Yudenich reached Gatchina, only 30 miles from Petrograd, on October 16.

In the next five days, NW Army rolled into Pavlovsk, Tsarskoe Selo, and finally Pulkovo, just 15 miles from the capital. Covered by the British fleet, a detachment of Yudenich’s marines also landed at Krasnaya Gorka, opposite Kronstadt, northeast of Petrograd.

In Paris, Sazonov made one last desperate plea for Finnish intervention to help Yudenich, proposing to Allied diplomats that they could use the “Brest-Litovsk” gold the Bolsheviks had shipped to Germany (now in Allied hands) to pay for it. In this aim he was supported by Mannerheim himself, who, after being ejected from power in July, had gone to Paris to lobby with everyone else. Would the Allies back Yudenich when it counted?

Without giving prior notice to his colleagues of a change in policy, Lloyd George simply announced, at the lord mayor’s banquet at London’s Guildhall on November 9, that Britain was giving up. “Russia is a quicksand,” he intoned darkly: it was time for Britain to escape before she was sucked in further.

The coming winter months, he suggested, would give all sides time to “reflect and reconsider.” When the text of this historic speech was published and transmitted to Russia, the effect on White morale, a British journalist accompanying Denikin’s army later wrote, “was electrical.”

Within days, “the whole atmosphere in South Russia was changed… Mr George’s opinion that the Volunteer cause was doomed helped to make that doom almost certain.”

It was not over quite yet for the Whites. Fighting fiercely to the end, the Volunteers held on in Kiev until December 16. On Denikin’s right flank, Tsaritsyn was abandoned only on January 3, 1920. Novocherkassk and Rostov fell on January 7, and the Whites prepared to evacuate beyond the Don.

By now the Don Cossacks had ceased fighting, leaving Denikin with no option other than to reenact a less inspiring version of the Ice March of 1918, pulling back toward the Kuban River. Denikin’s retreat turned into a general evacuation of “White Russia,” with civilian émigrés from the northern cities, joined by local Kalmyk, Tatar, Cossack and Circassian notables who had collaborated with Denikin, fleeing on foot with whatever they could carry. “The exodus of the Russian people,” as one White officer called it, “reminded me of Biblical times.”

In March 1920, Entente journalists recorded tearful scenes at Novorossiisk, as crowds of refugees tried to evacuate on the last British and French ships before the vengeful Reds closed in. Crimea, protected from the mainland by the easily defended Perekop Isthmus, was safe for now, guarded by a small rump army of Whites led by General Slashchev (who would soon surrender his command to Wrangel). But it could not be long before this last beachhead, too, was breached by the advancing Red armies

By October, the Reds enjoyed a two to one advantage in manpower (about 100,000 to 50,000) at the front, with massive Red reserves in the rear.

On October 14, just as the decisive battles were being joined on the northwestern and southern fronts, Frunze, who had taken over the overall command of Red Eastern Army Group, ordered Third and Fifth Armies to attack. The Whites fell back behind the Ishim River at Petropavlovsk, and then evacuated farther east when the Reds crossed the river, the last natural barrier before Omsk, on October 31.

Refugees now streamed into Omsk in terror of the advancing Reds, swelling the population of this provincial capital from 120,000 to over half a million. As one English officer recalled the scene: “Peasants had deserted their fields, students their books, doctors their hospitals, scientists their laboratories, workmen their workshops… we were being swept away in the wreckage of a demoralized army.”

On November 14, the Reds conquered Omsk without a fight, and the White exodus continued east into the vastness of the Siberian winter. The Trans-Siberian was clogged with bedraggled refugees, with thousands succumbing to typhus in the cramped, unsanitary railcars.

The Czechoslovak Legion, hopeful of avoiding the epidemic, began halting the eastward movement of trains from Omsk, stranding even “Supreme Commander” Kolchak, who had planned to set up a new government in Irkutsk.

For most of November and December 1919, Kolchak was held ransom by Czechoslovak guards at Nizhneudinsk, prior to being handed over to a Bolshevik Military-Revolutionary Committee in Irkutsk on January 21, 1920.

The details of the negotiations remain murky, but the upshot is that the Czechoslovaks turned over Kolchak and 285 tons of the Kazan gold reserves to the Bolsheviks in exchange for their freedom.* On the night of February 6–7, 1920, Kolchak was shot following a “trial” reminiscent of the one given the tsar in Ekaterinburg, and his body was pushed under the ice of the Ushakovka River. So ended the White movement in Siberia.

Scarcely had the White fronts quieted down than another foreign invasion came in spring 1920, from Poland. After observing the destruction of Denikin and Yudenich with satisfaction, Pilsudski had made methodical preparations all winter, assembling an army of 320,000.

Taking a page from the German playbook, Pilsudski signed a treaty, on April 21, 1920, with a three-man “Directory of the Independent Ukrainian People’s Republic,” headed by the Cossack hetman Semen Petliura, who came to Warsaw to sign.

Petliura conceded eastern Galicia to Poland in exchange for recognition of his authority in Kiev. Like the Germans, the Poles invaded Ukraine by formal invitation, which helps explain why it took them only two weeks to reach Red-held Kiev, which fell to a combined Polish-Ukrainian force on May 7, 1920, the Poles losing only 150 dead and 300 wounded. Wits in the Ukrainian capital noted that it was the fifteenth change of regime in three years.

The Polish invasion-by-invitation of Ukraine, dangerous as it was, was also tailor-made for Red propaganda. Pilsudski and Petliura were over-the-top reactionaries, the former an avowed Polish imperialist and the latter a Cossack strongman harking back to the seventeenth century.

The agitprop nearly wrote itself: indeed in Britain, linchpin of the wavering western Alliance, the Bolsheviks barely even had to try. By jettisoning the Baltic blockade, Lloyd George had already gone halfway toward accommodating the Bolsheviks. Under mounting pressure from the Labour Party, he would now go the other half.

In fall 1919, he had agreed to send arms to Pilsudski’s Poles. After the fall of Kiev on May 7, stevedores at the East India Docks went on strike, refusing to load a consignment of field guns and ammunition destined for Danzig. With the Labour Party in an uproar and believing (correctly) that the British public was weary of the failed intervention in Russia, Lloyd George’s cabinet spokesman informed the House of Commons on May 17, 1920, that “no assistance has been or is being given to the Polish Government.”

Although none of the Entente powers had recognized Lenin’s government, the reversal in British policy was nearly complete.7

Behind Red lines, the Polish invasion rallied many Russians to the Soviet regime out of simple patriotism. On May 30, 1920, Izvestiya published an appeal from the former commander in chief, General Brusilov, urging tsarist officers to enroll in the Red Army to see off the foreign invaders. Enough did to make a difference.

In early June, Budennyi’s First Cavalry Army pierced Polish lines outside Kiev. On June 12, Pilsudski sounded the retreat, allowing the Reds to take Kiev—in the sixteenth regime change of the revolution. By early July, the Polish retreat had turned into a rout, with a southwestern Red Army Group under Colonel A. I. Egorov advancing on Lvov, and a Western Army Group, commanded by Tukhachevsky, advancing into White Russia and Lithuania.

By early July, the Poles had been chased back to the Vistula, with Tukhachevsky’s armies seizing Minsk (July 11), Vilnius (July 14), Grodno (July 19), and Brest-Litovsk on August 1. “Over the corpse of White Poland,” Tukhachevsky exhorted his men, “lies the path to world conflagration… On to… Warsaw! Forward!”

Whether or not Warsaw would fall to the Reds, the Soviet counteroffensive provided a perfect backdrop for the Second Congress of the Communist International, which opened in Petrograd on July 19, 1920, just as the Red armies were entering Poland.

The lever used to pry open the proud socialist parties of Europe was simple: money. The Bolsheviks now possessed a gold reserve that had, in 1914, been the largest in Europe, even if it had since been reduced by the German reparations sent west in September 1918, the nearly 100 tons spirited away by the Czech Legion, and the bullion shipped to Stockholm to be melted down.

More relevant for the Comintern was the world’s largest jewelry hoard piling up in the Moscow Gokhran—jewels that could easily be smuggled into Europe. In 1919, Bolshevik couriers, according to one historian of the Comintern, had financed the embryonic Communist parties of Germany, Britain, France, and Italy with diamonds, sapphires, pearls, rings, bracelets, brooches, earrings and “other tsarist treasures” worth “hundreds of thousands of [tsarist] rubles.”

After the Second Comintern Congress, delegates were given diamonds to bring home, stitched into jacket cuffs or hidden in double-bottomed suitcases. Others carried cash, especially US dollars, which soon became the official currency of the Comintern, in which all accounts were kept (the official language, owing to the enduring prestige of Marx, was German).

On August 14, just after the Second Congress closed, Trotsky issued orders for the final offensive against Warsaw to begin. Somehow, despite tall odds, Pilsudski struck back with a blistering counterattack against Tukhachevsky’s flank on August 16, capturing ninety-five thousand prisoners and forcing three Red armies to pull back in what Poles christened the “Miracle on the Vistula.”

By September 1920, the Reds were retreating all along the line, falling back all the way into Ukraine, where Wrangel’s rump White Army was still encamped in Crimea.

Lenin and Trotsky sued Warsaw for peace. On October 12, 1920, Soviet diplomats signed a preliminary peace treaty at Riga, conceding huge swathes of western Ukraine in which lived nearly 3 million people (mostly Belorussians and Ukrainians), marking the final Polish boundary 120 miles east of the Curzon line drawn at Versailles.

Eight days later, after transferring troops east to achieve a crushing superiority over the Whites (133,600 to 37,220), the Red Army attacked the Perekop Isthmus. It was all the overmatched Wrangel could do to screen an evacuation from Sevastopol, aboard French and Russian ships bound for Constantinople. (There were no British vessels, as Lloyd George had stipulated in the cabinet on November 11, to Churchill’s horror, that Britain must not give Wrangel assistance even in evacuating women and children, much less fighting forces.)

On November 14, the last White troops, along with civilians lucky enough to talk their way aboard—in all 83,000 people—left the Crimea; most would never see their homeland again.

Some 300,000 unfortunate collaborators were left behind to face Bolshevik firing squads or be interned in concentration camps. In retaliation for helping Denikin and Wrangel, the Don Cossacks were expelled en masse from their homesteads. The Whites were finished.

Foreign intervention, along with the British blockade, had won the Bolsheviks a certain grudging sympathy from their rural subjects, as both fought the same enemies and suffered, to at least some extent, the same material deprivations.

The Red Army was itself a marriage of convenience between the Communist regime and Russia’s peasant masses, who supplied the manpower that allowed the Reds to defeat their foreign enemies largely by sheer weight of numbers.

In November 1920, the political dynamic was turned upside down. With the blockade lifted, the Bolsheviks were free to import as much military equipment as their tsarist gold bullion and Gokhran jewelry could buy—while facing, after the departure of the Whites and the Poles, only internal opposition from peasant partisans resisting grain requisitions, which now ratcheted up sharply.

There was another surge after the defeat of Denikin and Wrangel in February–March 1920, when the so-called Pitchfork Rebellion, encompassing an irregular peasant army of fifty thousand stretched out between the Volga and the Urals, forced Red commanders to deploy cannons and heavy machine guns.

Pilsudski’s invasion in April had, in strategic terms, piggybacked on the Pitchfork Rebellion, which so distracted Trotsky that he had temporarily left Ukraine and White Russia undefended.

The peasant wars may, in the end, have been a greater test of strength for the Bolshevik regime than the more publicized conflicts with the Whites, Entente expeditionary forces, Finns, and Poles. As Lenin himself pointed out, Russia’s peasants were “far more dangerous than all the Denikins, Yudeniches, and Kolchaks put together, since we are dealing with a country where the proletariat represents a majority

In October–November 1920, as if in lockstep with the departure of the last foreign armies from Russian soil,* the most ferocious peasant rebellions yet erupted against the Bolshevik dictatorship in the eastern Ukraine (led by Nestor Makhno’s partisans, who now numbered about 15,000), western Siberia, the northern Caucasus, Central Asia, the Volga region, and in Tambov province, only a few hundred miles from Moscow.

The partisans in the North Caucasus had about 30,000 under arms, in western Siberia as many as 60,000. In Tambov, a rebel chieftain named Alexander Antonov, drawing on no less than 110,000 Red Army deserters hiding out in the surrounding countryside, put together a partisan army of 50,000 men, divided up into eighteen or twenty military “regiments.”

This new class war pitted heavily armed Red Army troops or Cheka enforcers against peasant farmers, many of whom fought with pitchforks. In a typical Cheka directive in the north Caucasus, on October 23, 1920, Sergo Ordzhonikidze ordered that inhabitants of Ermolovskaya, Romanovskaya, Samashinskaya, and Mikhailovskaya “be driven out of their homes, and the houses and land redistributed among the poor peasants.”

The Cheka agents obliged, reporting to Ordzhonikidze three weeks later: “Kalinovskaya: town razed and the whole population (4,220) deported or expelled. Ermolovskaya: emptied of all inhabitants (3,218).” In all, some 10,000 peasants had been expelled, with another 5,500 shortly to suffer the same fate.

Each clash between the Cheka or “food armies” and partisan rebels fueled a vicious cycle, as peasants hid their grain or deliberately stopped growing crops, leading frustrated Communist requisitioners to denounce the “kulak grain hoarders” and demand yet more brutality in dealing with them.

By winter 1920–1921, huge swathes of rural Russia were approaching famine conditions. In Tambov province, where Antonov’s peasant rebellion was so huge that the Red Army was called in, the commander in charge of suppressing the partisans, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, openly admitted that, by January 1921, “half the peasantry was starving.”

In the Volga basin, conditions were even worse. In Samara province, the commander of the Volga military district reported that “crowds of thousands of starving peasants are besieging the barns where the food detachments have stored the grain… the army has been forced to open fire repeatedly on the enraged crowd.”

In Saratov, heavily armed partisans, after obtaining rifles from Red Army deserters, had recaptured the grain stocks requisitioned by the food armies. Ominously, the local Soviet reported to Moscow that “whole units of the Red Army have simply vanished.”

Between January and March 1921, Soviet sources indicate, the regime lost control of whole areas of the middle Volga and western Siberia, including the provinces of Tyumen, Omsk, Cheliabinsk, Ekaterinburg, and Tobolsk—and of the Trans-Siberian railway itself.

The food wars now crashed into Moscow and Petrograd. On January 22, 1921, the bread ration in both cities was reduced by one third, to 1,000 calories a day, for even the privileged laborers of heavy industry, costing Lenin’s government the support of even its diehard backers; only 2 percent of factory workers now belonged to the party. Strikes and protests rocked Petrograd.

On March 8, the local Izvestiya hit the Bolsheviks where it hurt. “In carrying out the October Revolution,” the paper announced, “the working class hoped to achieve its liberation. The outcome has been even greater enslavement of human beings.” Instead of freedom, Russia’s urban workers now faced “the daily dread of ending up in the torture chambers of the Cheka,” while her peasant masses were being “drenched with blood.” A “third revolution” was at hand, in which “the long suffering of the toilers has drawn to an end.”

The Red Terror had been aimed at “class enemies”; the Civil War was a struggle against “imperialists and White Guards.” Even the peasant wars had pitted, in theory at least, proletarians against “capitalist farmers.” But now the world’s first “proletarian” government had begun slaughtering urban proletarians, too.

It is no wonder that “Kronstadt” became, in addition to a black mark on Trotsky’s record, a byword of Bolshevik betrayal for European socialists who refused to bow to Moscow.

Harder to explain is why it was in this very week in March 1921 that Lenin’s Communist dictatorship was beatified by Britain, after months of diplomatic courtship. Lloyd George affixed his signature to the historic Anglo-Soviet Accord on March 16, the very day the Bolsheviks blackmailed Sweden into cutting off the Kronstadt rebels and on which Trotsky launched his final bloody assault.

Although on paper a mere “trade agreement,” the accord granted Soviet and British trade officials rights equivalent to those of consular personnel, from the use of ciphers and sealed diplomatic bags, to the recognition of valid passports.

By agreeing to Soviet demands that the British government vow never to “take possession of any gold, funds, securities or commodities… which may be exported from Russia in payment for imports,” the accord formally ended the gold blockade, forfeiting any leverage Entente governments still had to force Moscow to pay old debts.

Lloyd George’s protestations aside, his government had granted de facto recognition to Lenin’s, giving up the right to “express an opinion upon the legality or otherwise of its acts,” as the British Court of Appeals ruled as early as May 1921, and as British courts have ruled ever since.

Angry farmers fought back with whatever tools they had on hand, bludgeoning to death, according to the regime’s figures, eight thousand Bolshevik food requisitioners in 1920 alone. The peasant masses of the Volga region, one Cheka agent reported to Moscow, now genuinely believed that the “Soviet regime is trying to starve all the peasants who dare resist it.”

The regime’s abandonment of the prodrazvërstka in March 1921 was a step in the right direction, but Lenin’s truce with the peasants was belied by his reaction to the famine. The regime did spend some money on food imports in May and June, but these were for the cities, and they mostly consisted not of grain and seed, but perishable luxuries such as Persian fruits, Swedish herring (40,000 tons), Finnish salted fish (250 tons), German bacon (7,000 tons), French pig fat, and chocolate.

As one of Lenin’s own purchasing agents later recalled with a shudder, Communist elites in Moscow and Petrograd were consuming “truffles, pineapples, mandarin oranges, bananas, dried fruits, sardines and lord knows what else” while everywhere else in Russia “the people were dying of hunger.”

Far from easing up on the starving peasants of the Volga basin, on July 30, 1921, Lenin instructed all regional and provincial Party committees to “bolster the mechanisms for food collection” and to “provide the food agencies with the necessary party authority and the total power of the state apparatus of coercion.”

Fortunately for the starving, there were other Russians with a conscience in Moscow and Petrograd who shamed the government into action.

Moscow Agricultural Society. Earlier in June, this group had formed a “Social Committee for the Fight Against Famine,” recruiting, among others, journalist Ekaterina Kuskova, the wife of a good friend of renowned novelist Maxim Gorky.

Gorky had known Lenin for over two decades, and had raised money for the Bolsheviks before the war. Although he had criticized many of the regime’s repressive policies, his international fame furnished him protection during the Red Terror.

Once Gorky learned of the scale of the famine, he agreed to issue an appeal “To All Honorable People” on July 13, 1921, soliciting aid from the international community. He also lent his name to the new “All-Russian Public Committee to Aid the Hungry” (Pomgol), an ostensibly private (actually regime-controlled) charity organization founded on July 21, which enabled Lenin’s Communist government to solicit foreign aid without appearing to beg for bread from “capitalists.”It worked.

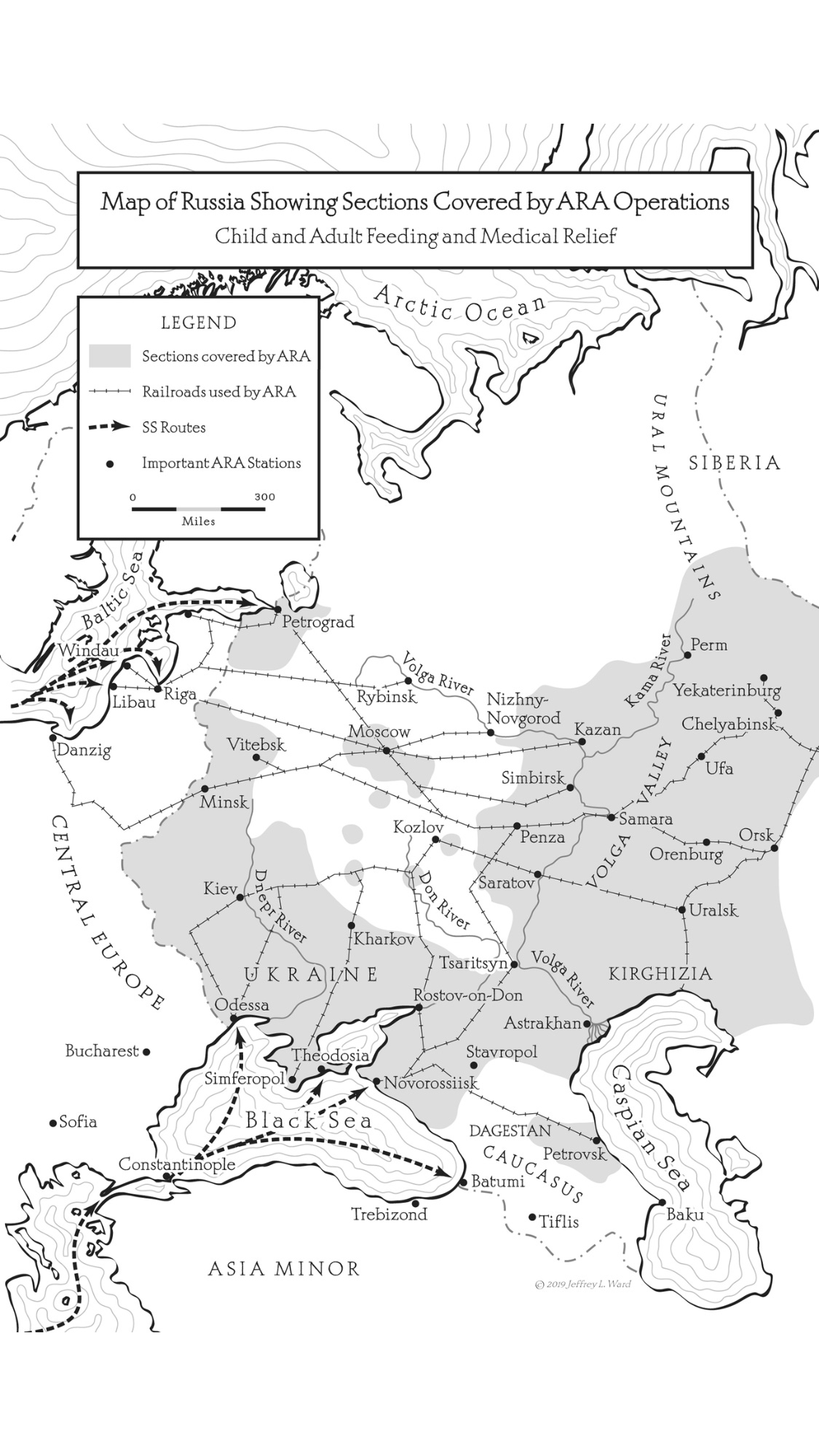

On July 23, US secretary of commerce Herbert Hoover, whose American Relief Administration (ARA) had disbursed American food aid in stricken postwar Belgium and Hungary, responded to Gorky’s appeal. Negotiations were then carried out in Riga, in which the lack of trust was obvious.

Hoover insisted on independence from Soviet government interference, along with the release of US nationals held in Communist prisons and concentration camps. Lenin was so infuriated by these demands that, while agreeing to sign, he ordered the Cheka to infiltrate the ARA with “the maximum number of Communists who know English.”

Lenin also issued a public appeal “to the workers of the world” on August 2, in which he alleged that “the capitalists of all countries… seek to revenge themselves on the Soviet Republic. They are preparing new plans for intervention and counter-revolutionary conspiracies.”

Before they went to work alleviating the Volga famine, Hoover’s aid workers had already been placed under suspicion (and surveillance) as “counter-revolutionaries.” Nonetheless, they performed heroically. Primed by an appropriation of over $60 million from the US Congress, the ARA established a first-class operation in Russia.

By the end of 1921, the ARA, along with other “bourgeois” charity organizations, such as the American Red Cross, Quakers, and the Federated Council of the Churches of Christ, had shipped to Russia over two million tons of grain and foodstuffs, enough to adequately feed 11 million people, along with seed sufficient for the next two years’ harvests.

Although 5 million died in the Volga famine that summer and fall, by early 1922 reports of starvation had virtually ceased. So efficient was the ARA’s work that the Soviet government expressly requested that the ARA curtail aid shipments into the ports of Reval, Riga, and Petrograd, “owing to their inability to handle such large quantities.”

The success of the “capitalist” Americans in feeding millions of Russians starving under Communist rule was politically embarrassing.

The Volga famine also brought to a boil long-simmering tensions between the Communists and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Although church property was nationalized in January 1918, very little had actually been taken, owing to Lenin’s fear of arousing popular resistance.

The onset of an almost nationwide famine in June 1921, compounded by the snuffing out of the Tambov rebellion, altered the equation. Peasant resistance was now crumbling, overriding Lenin’s reservations about targeting the Church.

Meanwhile, Patriarch Tikhon had embarrassed Lenin no less badly than had Hoover with his own response to the famine. By the end of June 1921—more than a month before Lenin had issued his own appeal to global “proletarians”—Tikhon had printed up 200,000 copies of a moving appeal to Russia’s Christians to “take the suffering into your arms with all haste… with hearts full of love and the desire to save your starving brothers.”

The patriarch then established his own famine relief committee, which collected 9 million rubles. On August 22, 1921, Tikhon wrote to Lenin, asking permission for the Church to be allowed to buy food supplies directly and organize relief kitchens in famine areas. Enraged by the patriarch’s impudence, Lenin ordered Tikhon’s famine relief committee dissolved, arrested its leaders, and exiled them to Russia’s far north.

Tikhon, still under house arrest, continued receiving donations, but he was forced to turn these over to the government. By sticking his neck out for the starving peasants of his flock in summer 1921, Tikhon had provided Lenin a pretext to end his truce with the Orthodox Church.

An ill Lenin cut back his work schedule in fall 1921, decamping to his country dacha south of Moscow. In his absence, Trotsky took over the “famine” brief for the Politburo, by which was meant not food aid—Hoover’s ARA was taking care of this—but the politics of famine.

In November 1921, Trotsky was appointed to head a new commission overseeing the sale of Gokhran treasures abroad, ostensibly for famine relief. The idea was to seek out such treasures in the Church. Trotsky dropped hints in the press that the Church was not “doing enough” for relief. Why were clergymen not, one article demanded, using their “gold and silver valuables” to buy “grain [which] could save several million of the hungry from starvation”?

“Citizen letters” were then published in Izvestiya and Pravda, supporting confiscations of Church valuables. Many of these came from “progressive” clergymen of middle rank—regime collaborators known as renovationists—who hinted darkly (and absurdly) that Patriarch Tikhon was threatening famine donors in the Church with excommunication.

Tikhon fell for the bait. After the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) ordered the expropriation of Orthodox Church valuables for famine relief on February 23, 1922, Tikhon declared this Bolshevik decree a “sacrilege” and threatened to excommunicate anyone who removed “sacred vessels” from the Orthodox Church, “even if for voluntary donation.”

Tikhon did allow, on February 28, that parishioners might donate saleable Church valuables to help feed the hungry, so long as they “had not been consecrated for use in religious ceremonies.” Such vessels could be surrendered to the government, Tikhon and the Orthodox Metropolitan of Petrograd, Veniamin, declared, only if the Bolsheviks could provide assurance that resources were exhausted, that “proceeds would truly benefit the hungry,” and that Orthodox clergymen would be allowed to “bless the sacrifice.”

There was more to the Church looting campaign launched on February 23, 1922, however, than ideology. The dire financial straits cited in Trotsky’s agitprop were real, although Trotsky was lying about the reason the government suddenly needed the money so badly.

Hoover’s ARA was providing famine relief to Russia essentially free of charge, and it was this very month that the Soviet government, satisfied with Hoover’s performance to date, requested that the ARA slow down shipments of food aid, as Hoover personally informed US President Warren Harding on February 9.

Earlier that same week, in a development unrelated to either the ARA or to famine relief, the last shipment of tsarist gold bullion (44 tons) left Reval on February 6, destined for Stockholm. On February 7, Trotsky revoked authorization for Soviet purchasing agents abroad.

In terms of gold bullion—which they needed not for famine relief, but to pay for weapons and other strategic imports—the Bolsheviks were, by February 1922, effectively broke. Trotsky knew that the regime was approaching bankruptcy beforehand, of course. The church looting campaign was settled on long before its announcement on February 23, 1922, and the Patriarch’s pitch-perfect protest lodged in response.

It had been meticulously planned out in advance the previous December at a series of closed-door sessions of Sovnarkom, the Politburo, and the party’s Central Committee, culminating in a top-secret VTsIK resolution “on the liquidation of Church property” passed on January 2, 1922, which explicitly stated that valuables obtained from the Church would go not to famine victims, but to the State Treasury of Valuables (Gokhran). All trains on which looted Church vessels were transported would be guarded by Red Army officers, who were required to inform the Gokhran, by telegram, of “the number of the train, the number of the wagon, and the time of departure.”

All communications from looting teams in the field were to be conducted only with senior Gokhran officials. Small wonder an operation ostensibly devoted to famine relief was entrusted to the Red Army and the Cheka, now renamed the State Political Directorate (GPU), and directed by Trotsky, the commissar of war.

The church robberies shocked European and American opinion. As the New York Times reported in April: “[Russians] have seen their churches invaded by bands of armed men who seem quite as eager to destroy as to remove the sacred ornaments… in many places parties of men, women and children, unarmed but determined, have formed a circle round their church and dared the Soviet troops to do their worst.”

Amsterdam’s De Telegraaf ran sensational headlines all spring: “Desecration of Minsk churches”; “Orthodox priests sentenced to death for resistance”; “Bloody clashes in Kiev.”

Thanks to the tireless efforts of Hoover’s ARA and its brave Russian employees, the Volga region enjoyed a bumper harvest in summer 1922. Over the preceding year, the Soviet government had quietly relegalized many private economic activities, from the retail sale of agricultural and manufactured goods (July 19, 1921) to real estate transactions (August 1921), publishing (December 1921) and small-scale manufacturing (June 1922).

The critical month was April 1922, when the Bolsheviks, by restoring the right to own hard currency and precious metals without fear of confiscation, effectively re-legalized money. By the time the gold ruble was in circulation and Ruskombank was chartered in November 1922, the wages of this “New Economic Policy” (NEP) were clear, if unexpected.

With the exception of heavy industry, banking, and foreign trade, which Lenin famously called the “commanding heights” of the economy, Russia’s Communist rulers had brought back—capitalism.

Stalin exploited Lenin’s January 1924 funeral to erect a quasi-religious personality cult, embalming the body of the Bolshevik Party leader and then erecting a mausoleum in Red Square to house it as a site of pilgrimage.

In terms of the relationship between government and governed, ruler and ruled, it seemed that one Russian autocracy had simply been substituted for another.